When Matt Jansen thinks of the summer of 2002, the memory is so vivid it is easily distilled. “The happiest man in the world,” he says. “That’s exactly how I felt.”

Those six words form the title of the opening chapter to Matt’s new autobiography. He also said them out loud, in Rome, where he was floating on his cloud.

At his peak as a Premier League footballer, with the girlfriend he already knew would be his wife, Matt could not imagine how precarious this happiness was. Those six words are bittersweet because, on the final night of their Italian holiday, everything changed.

Former Carlisle United player Matt and Lucy went out on a hired scooter and, at a crossroads, where visibility was poor in congested streets, they were struck by a taxi and thrown onto cobbles. Lucy was largely unhurt but Matt, from Wetheral, slipped into a six-day coma.

This was only the beginning of a gruelling road which Matt, 17 years on, has finally committed to print. The “game of two halves” football cliché is a perfect fit for his story and the book, on which we collaborated, charts his thrilling rise and traumatic fall.

After speeding to stardom at Carlisle, progressing to Crystal Palace and then Blackburn Rovers, Matt reached a crescendo when scoring in the League Cup final and then being selected by England.

An untimely bout of gastroenteritis cost him his international debut, and then he was narrowly overlooked for the 2002 World Cup, but Matt did not lose sleep over this rejection. He knew his time was coming.

After Rome, though, it never did. Matt recovered physically and was soon back on the pitch. Mentally, though, the scars were deep, and strange.

“Barry, my father-in-law, describes it as a snowglobe,” says Matt of his head in this period. “It had been given such a heavy shake, and by the time I was playing again, all the snowflakes hadn’t settled.”

What this means is that Matt, who had been a freewheeling and, in his own words, “invincible” attacking player, needed to re-learn the basics of football after the accident. This saw a once glorious footballer shrink within himself. What had been instinctive and sharp was now painstaking and slow.

As he groped for the old feelings on the training ground and in stadiums, his mind rebelled. He wanted to play, but he didn’t. He wanted the ball, but couldn’t bear for people to see a lesser version of himself. He still loved football, but now also hated it.

His ego, which had swelled over several years, had popped. Anxiety turned into depression and, as his career flatlined, he tried to blur the edges. Sometimes with alcohol; once, as the book hauntingly describes, with a fistful of painkillers thrown down his neck during a tearful night at home (“a cry for help,” he says).

At other times, with the help of Professor Steve Peters, who famously worked with champion cyclists and other elite sports people. Peters introduced Matt to his “chimp” theory of mind management, and made some productive headway, but not enough to repair his career.

Matt joined other clubs, such as Bolton Wanderers, but it was not until he retired, and became a coach and manager, that he gained the perspective to relive all this. He is now 41, a father of three, and keen to share his story in the hope it will help enlighten others about mental health.

“When I was a young player at Carlisle,” he says, “I didn’t believe in sports psychology. I remember [director of coaching] Mick Wadsworth bringing in Bill Beswick, who was well-known in that field, to work with us.

“I just laughed. ‘What do I need a psychologist for?’ I thought it was a load of rubbish. Now, through a horrific experience, my view has changed completely. I feel that everything I’ve been through has given me an insight into how the mind works. Without the accident, I wouldn’t have had that.”

Without the accident, England may also have had an outstanding Cumbrian footballer, and this is the deep regret of Matt’s story. He played locally for clubs such as Denton Holme and the Ex-Servicemen’s and also joined Carlisle’s youth set-up amid a rich crop of talented Cumbrian players in the 1990s.

Matt broke into the first team in 1996 and within a year had Manchester United beating a path to Brunton Park. Remarkably he said no to Sir Alex Ferguson, instead signing for Crystal Palace because he felt first-team football was more attainable there.

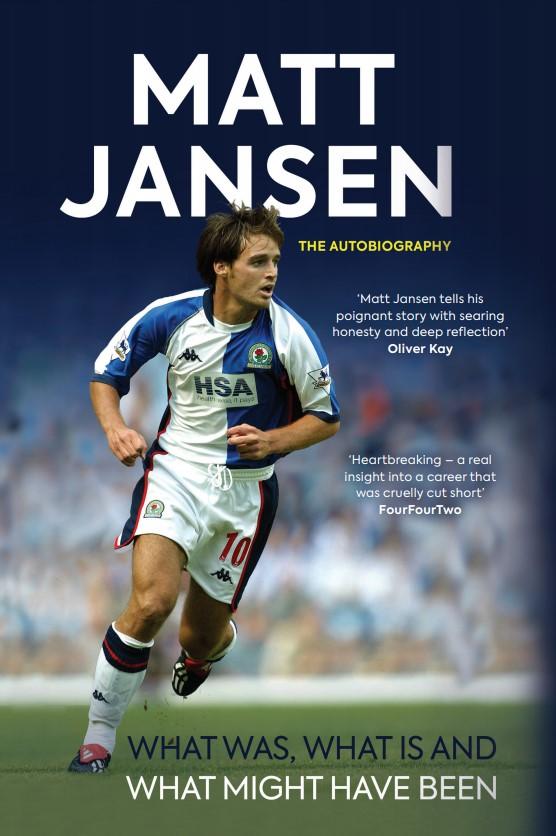

Blackburn followed in 1999, and it was there that he became a legend, helping Rovers to promotion, establishing them in the Premier League, winning the 2002 League Cup final and, at 24, entering Sven-Goran Eriksson’s thoughts for England.

As well as documenting the post-accident fall-out, plus carrying insights from managers such as Graeme Souness, Sam Allardyce and Eriksson, the book charts Matt’s childhood. This includes a description of the bullying he suffered at Austin Friars School, the happiness he found at Newman Catholic School, the brutal dressing-room rituals he faced at Brunton Park and inevitable cameos from Michael Knighton.

It is also, at its heart, a love story. Matt and Lucy, who met because they shared an apartment block in Manchester, had only been dating for weeks when they went to Rome. They married two years after the crash and survived fate at its most challenging. They live in Alderley Edge in Cheshire with sons Freddie and Arthur and daughter Minnie.

“My lowest lows were in that time when I was trying and failing to get back to the standards I’d reached as a player,” Matt says. “I was in a dark place and I must have been a nightmare to live with. I was depressed, drinking too much, hating myself. Lucy helped me get out of the other side. She was a rock.”

Until last year Matt was manager of Chorley, and says this role helped free him from the torment of trying to retrieve his playing days. He is also able to revisit Rome with a clear mind - as he did earlier this week with a journalist as part of the book's promotion - because he cannot remember the immediate aftermath of what happened there in 2002.

He was linked with the Carlisle job last summer and, as he awaits his next football role, is certain he has plenty to give. Can he, though, be the happiest man in the world again? “I don’t know,” he smiles. “But I’m in a much better place than I was a few years ago. When I was playing, my ego was like a snowball, growing and growing until that day in Rome.

“At this point it’s about building a new snowball and seeing how big I can make it."

* Matt Jansen, The Autobiography: What Was, What Is and What Might Have Been is published by Polaris.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here