An exclusive extract from the autobiography of former Carlisle United player Joe Thompson, which charts his career and remarkable recovery from two cancer battles.

I made my Carlisle debut in a 4-4 draw against Cambridge United in our second league game of the season. It was one of the most emotionally draining games I’ve ever experienced. The following week I scored my first goal since returning from cancer on a Tuesday night trip to Plymouth.

We lost 4-1, and it was a terrible team performance, but I felt like a weight had been lifted off my shoulders.

It had been over 12 months since I’d last hit the back of the net and until that moment I didn’t truly feel like I was back.

I didn’t start every week, but I featured regularly up until Christmas when my six-month deal was due to expire. I felt I’d won Keith Curle’s trust and was confident I’d be offered another contract until the end of the season, but I very nearly undid all my good work shortly before the floods hit in December.

It was a Friday afternoon and me and the rest of the boys in the house were relaxing after training, ahead of our game the following day. But we also had another important event in the football calendar to prepare for - the annual Christmas party.

The squad had decided to go to Edinburgh for a good knees-up after the Crawley game to celebrate a positive first half of the season. We stopped off at the shops after training to buy a few beers and put them in the fridge to chill. All of our going-out gear was ironed and hung on a big rail in the back room so we could put it in our suitcases and have a couple of beers on the train to Edinburgh.

Suddenly the front door swung open. “Afternoon gentlemen, how are we doing?” asked a familiar voice. It was Keith Curle. He’d walked in without knocking and was heading for the living room. I picked up the rail with our clothes on and chucked it over the other side of the sofa. There was a dart board near the table, so two of us pretended we were playing a game of arrows to guard our stash of ale.

“So, this is how you spend your afternoons, is it?” he laughed, as he saw us throwing darts into the board. “I thought I’d come and check that you’re looking after this place.”

He made a bit more small talk and then went upstairs to have a look around the bedrooms before deciding he was satisfied with his inspection. As soon as the door shut we all collapsed laughing. We were so relieved we’d got away with it. If he’d found the beers I’m certain he would’ve gone mental and accused us of not focusing on the game.

It was one of many funny memories I’ve got of living in that house. On one occasion, Charlie Wyke thought it’d be hilarious to tip my bed up with me still in it, just after I’d turned the light off. I threatened him with revenge but he didn’t listen.

All the lads were professional when it came to football, but I felt like I was sampling university life without the midweek booze-ups. Sadly, the floods meant we had to move from hotel to hotel until the final weeks of the season, which meant our little family unit was broken up.

I’d done everything that had been asked of me and Keith rewarded me with another contract, which took me to the end of the season. My relationship with him was the best I’d had with a manager since my days working under Keith Hill at Rochdale.

I knew we’d get on from the moment I first met him at the training ground. I remember watching him as a player and he was a fierce competitor but as a manager he’d often bottle up his rage. If you continuously hammer players the impact wears off and I think he was aware of that.

I’d sensed that we’d been close to seeing his angry side come out on a couple of occasions after poor performances and got the feeling he wouldn’t be able to contain it forever. It turned out I was right.

Players and managers all have their own habits. Before every game Keith liked his dressing room to be organised in a very specific fashion. His habits were bordering on OCD. In his head, a clear dressing room meant a clear mind.

After a dismal 1-0 defeat at Newport, on a freezing February afternoon on a terrible pitch, he noticed that something was out of place. The kitman and Lee Fearn, our physical conditioning coach, had made the mistake of having a tidy up and had moved things from their normal stations. It tipped him over the edge.

“Why are all those protein shakes in the middle?!” he shouted, pointing at the plastic shakers sat on the table. I knew that any moment they were about to go everywhere. Seconds later he erupted and started throwing shakes all over the dressing room. There was pink liquid splattered over everyone.

He then grabbed a basket full of GPS monitors and began launching them at everyone, bouncing them off the floor and walls. Everyone was ducking and diving like a boxer trying to slip punches.

There was a stunned silence, before he began his verbal attack. “None of you have got the ******** to get up and say anything because you know I’ll bite your ******* face off,’ he screamed. ‘I’m ******* right and you know it, you tossed it off, not one of you fancied it today!”

He used to play for Wimbledon during the Crazy Gang era and now I could see why he fitted right in. Sometimes you feel hard done to when a manager has a go at you, but on this occasion he was right to be livid.

The journey home felt like a funeral procession. Keith had the respect of everyone, but he definitely had more power after that dressing down because his reaction had come as such a shock. I secretly loved it.

Nobody wanted to risk a repeat, and it was no surprise that we went on a good run in the aftermath of that game. Unfortunately I found myself on the bench as the season drew to a close, though I was happy with my performance on the final day, as we thumped Notts County 5-0.

Keith had been sacked by the club a couple of years earlier and I could tell that result meant a lot to him. He’d stuck two fingers up to them and showed them what he was capable of. As a squad, it was a display that highlighted how much we were behind him.

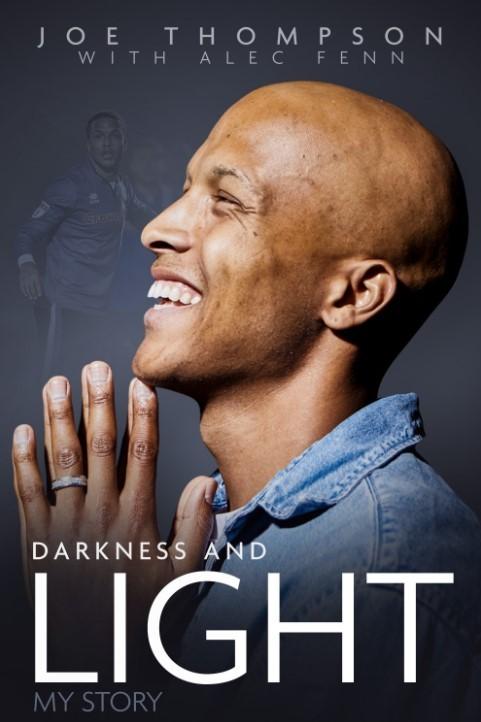

* Darkness and Light, by Joe Thompson with Alec Fenn, is published by Pitch Publishing, priced £18.99.

Next Wednesday: how Storm Desmond tested club and city

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here