When people think of Mike Sutton at Carlisle United, it is often with a smile at the recollection of a fine footballer and a distinctive man. Sutton was one of those players who both made things happen on the pitch and ensured his team-mates were aware of a particular set of standards.

“He was a health fanatic, always eating all the right stuff, no junk,” says Frank Barton, a team-mate in Sutton’s seasons at Brunton Park from 1970-2. “He even taught me how to grow yoghurt cultures so I could eat more healthily. He was a great guy, very hard-working, very strict with himself.”

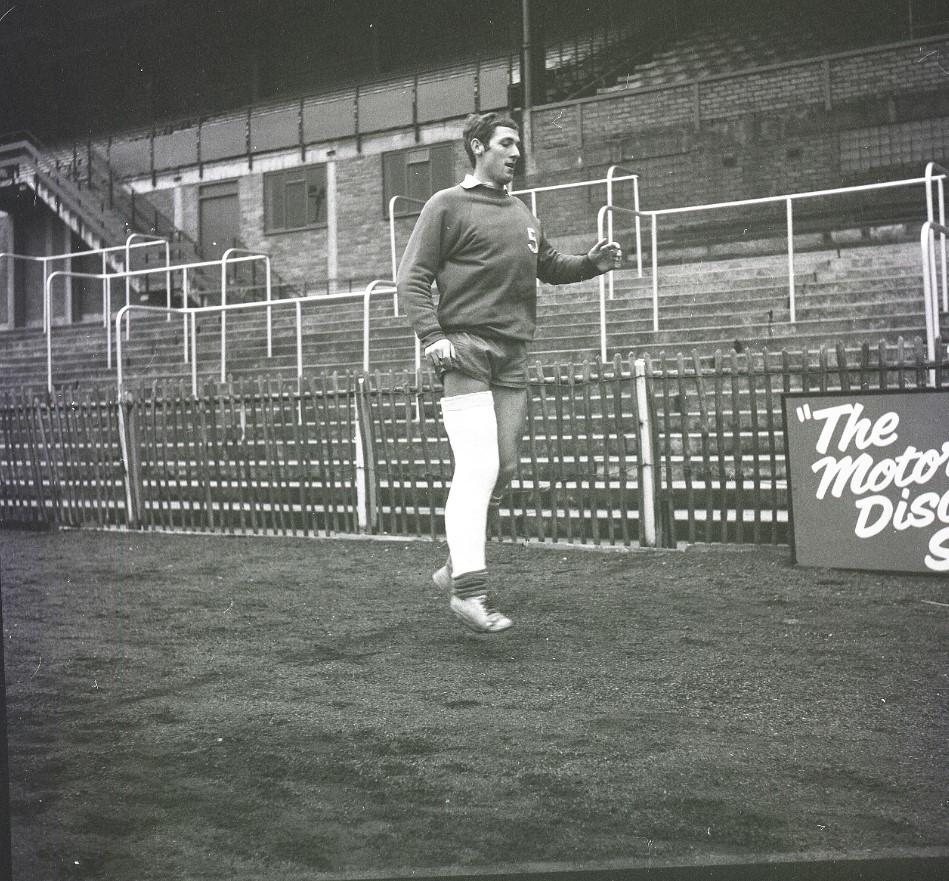

Sutton is also in that special category of United player to score on his debut, against Middlesbrough, and, as a versatile and astute reader of the game from midfield, gave Carlisle 60 committed appearances in teams that included luminaries like Stan Bowles, Bob Hatton, Chris Balderstone and Stan Ternent.

“My grandmother always used to keep cuttings, and there are pictures of him in those Carlisle teams,” says Mike’s son Chris, the former Premier League and Scottish Premiership striker and broadcaster. “It was in the later stages of his career, having started at Norwich City, then moving to Chester for three seasons before heading up to Carlisle. As far as I’m aware there was a transfer fee involved.

“He always spoke fondly of the area, of the team and of Brunton Park. When I was lucky enough to play there myself, as a young player at Norwich [in the League Cup in 1992], it was nice to go up and witness a ground where my dad had played.”

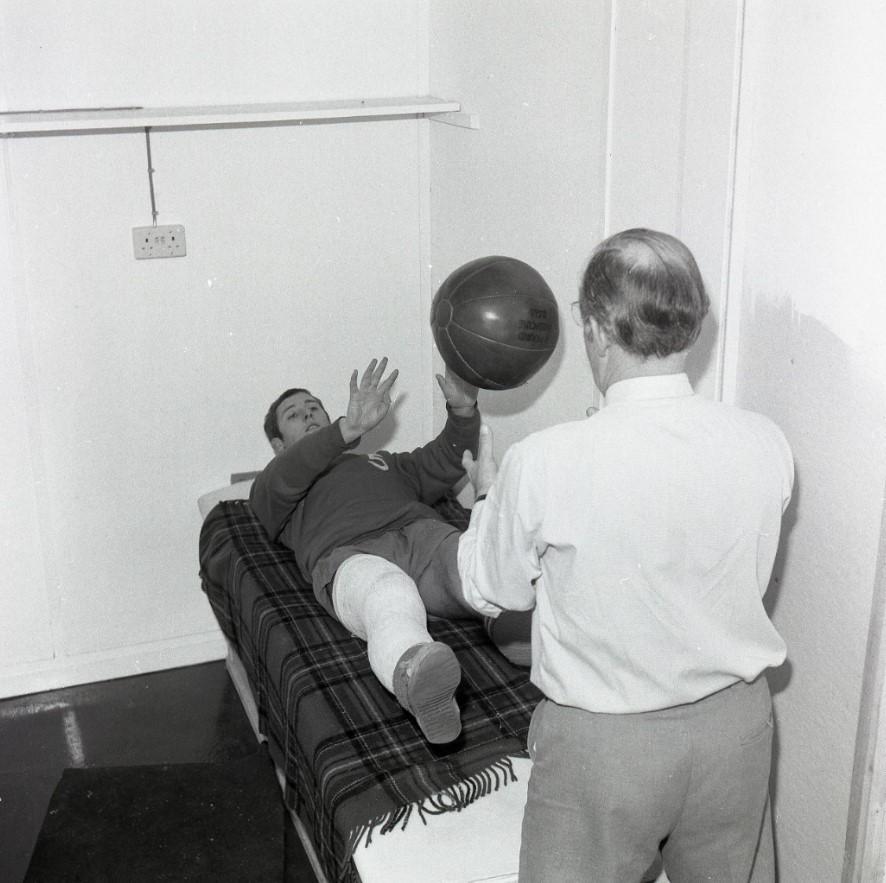

Sutton junior, who starred for Norwich, Blackburn, Chelsea and Celtic, owes his career to his father. He talks about the time he was rejected by Norwich at 12 and Mike, by then a teacher after injuries led to retirement at 28, dragged him out of bed and urged him into regular fitness drills in the school gym. This bred a new athleticism and determination in Chris which led to a second chance at Carrow Road. He spectacularly seized it, going on to become Britain’s first £5m player in the vivid early years of the Premier League.

“I would describe my dad as super-driven as a person,” Chris adds. “He was hard on me, quite straightforward and up front, and would tell me what he thought of my performances.

“Those years under him made me. Away from football I have fond memories too. When he moved from Loughborough University to Norfolk to become a teacher, it was a bit like The Good Life [the 1970s sitcom]. We had goats, chickens and grew our own vegetables. I wouldn’t describe us as hippies but we probably weren’t a million miles off.”

Chris, whose two older sisters were born in Carlisle and whose younger brother John briefly represented the Blues, recounts these memories because his father cannot. Mike Sutton’s mind and body have for the last 10 years been gradually smothered by dementia.

“The first time alarm bells started was when he was travelling home after watching my son play football, and he got lost,” Chris says. “My dad knew the area as well as anyone and could normally find any village or sports ground in the county [Norfolk].

“That’s when the worry started. He went to the doctors and had tests. They wouldn’t really commit to anything but over time we all became well aware of the issues which he has. Over the last decade he’s been in a gradual decline and is in a state now where he’s lost his dignity. He can’t eat properly, he can’t toilet properly. He gets spoon-fed, he can’t clean his teeth or shave. He can’t walk now. We missed five months of visiting him because of the [Covid-19] lockdown, and when I went to see him again, he was being pushed in his wheelchair and didn’t know what he was doing.

“He’s just a shadow of what he was. It’s really sad for my mum, who has been with him 56 years. He’s in a home now because it got to a situation where she couldn’t cope any more. He would disappear, leave the house, couldn’t find his way home. Fortunately she would put his name and her number inside his jacket. But it became a 24-hour issue. He could just get up and bolt.

“It’s been an awful, awful decline and nothing is able to halt it. All I can do is go and visit him, hold his hand and sit and talk to him. I just hope some of my words get through and he does understand. But that’s just hope. Nothing comes back.”

Chris shares this raw account not just to highlight the pitiless reality of his father’s condition. It is because he believes football has failed Mike, who is now 75. He is fervently critical of what he regards as the Professional Footballers' Association’s sluggishness in supporting and funding research into links between repeatedly heading a ball and neurodegenerative diseases.

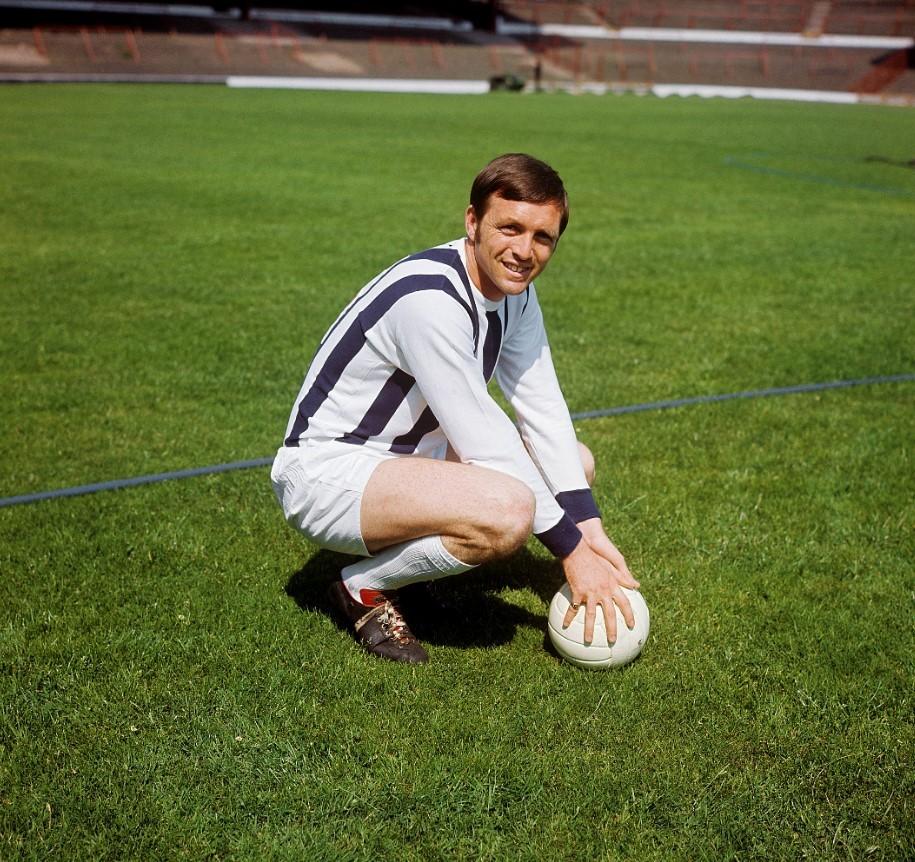

This has been in public light since a coroner ruled in 2002 that Jeff Astle, the great West Brom and England striker, had died by “industrial disease” – namely a brain injury caused by heading heavy footballs, something Mike and those of the same era routinely did. Other players, such as the World Cup winner Nobby Stiles, are also suffering from dementia and while the PFA have claimed to have been “committed to research in this area since 2001”, Sutton is aghast that many years passed without significant action, and that he and others, such as Astle’s daughter Dawn, feel they have always been pushing uphill in their bid to make the game realise its obligations.

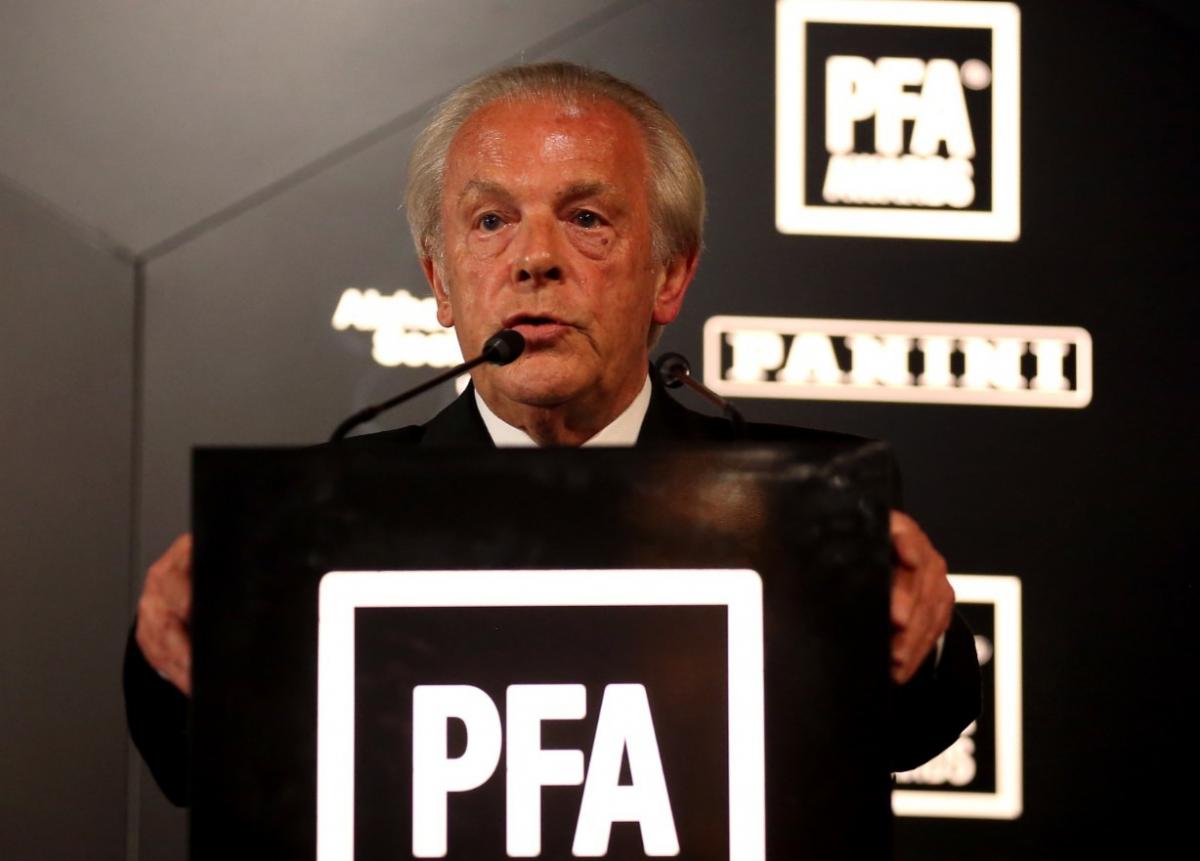

Gordon Taylor, the long-standing head of the players’ union, is a pointed target for criticism. “The reality is this,” Chris says. “Nothing can be done to save my dad now. But not enough has been done. Testing was being done, then it stopped – not a problem, because not everything works – but it took over a decade for it to come out that it had been stopped. It was Gordon Taylor’s duty of care to his members, like my dad, to say it had stopped but it was going to start up again. That is a scandal in my eyes and it has never been satisfactorily answered.

"A lot of high-profile people don’t want to get involved in this subject. But in 15-20 years’ time, when players from my generation are suffering with Alzheimer’s or dementia, our families will be saying, ‘Why didn’t we do something? Why didn’t we make more of an effort back then?’”

In very recent times there have been moves to ban heading in children's football. Sutton regards these as sensible. He remembers heading "100 balls a day" when practising as a young player and says that, had he known of the apparent risks, he would have been empowered to refuse.

He also cites research in 2016 regarding the 24-hour memory impairment suffered by people who head a ball 20 times in one day. He refers to the documentary made by Alan Shearer in 2017 which saw the England legend undergo tests himself.

He also mentions a landmark study by Glasgow University in 2019 which found that former footballers were three times more likely to die of dementia than non-footballers of same age range. The latter was commissioned by the PFA’s charity and the Football Association and, upon its publication, Taylor stressed that “our members’ well-being is of paramount importance to us” and research “must continue”.

Chris, though, says these were sporadic, belated steps that have lacked game-wide momentum. “Gordon Taylor is the great survivor,” he adds. “Look – he may have done a lot of good things for footballers over the years, and I also know there are arguments about his salary and the PFA buying paintings for millions of pounds. I’m not gonna get into that. I keep this pretty simple. Has the head of the players’ union done enough to help players with the issue of dementia? Absolutely not.

“There are hundreds and thousands of families around the country who are going through the same as my family is, seeing them live the most horrible life, seeing their condition degenerate and seeing them die in the most undignified way. We all feel the same. It will not get better with the wrong person in charge leading football’s fight against dementia.”

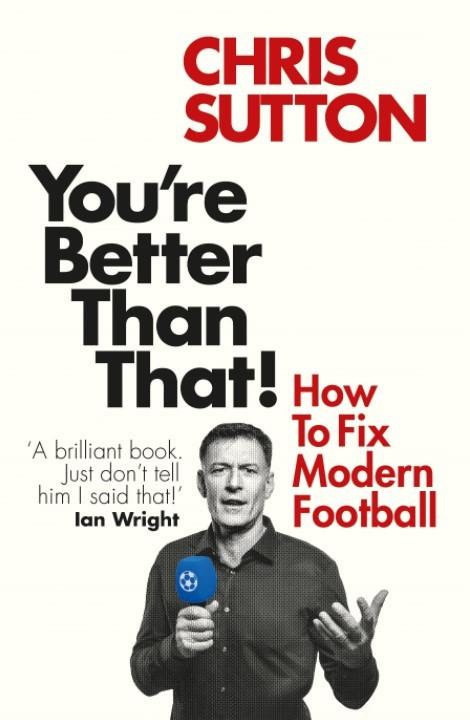

Sutton writes passionately on this issue in his new book, You’re Better Than That!, which offers arguments on and solutions to what he perceives as problems holding the game back. He is also considering legal action in light of his view that football has let his father down.

Though their cases may not be publicly known, there are Carlisle players from Mike Sutton’s time suffering similarly. Chris believes his father would be proud of his outspoken campaigning, but adds: “All I’m trying to do is raise awareness that there’s a serious issue here. I don’t think that’s remarkable.”

It is stark to hear Chris declare with conviction that his father, if he had known about the condition that was to befall him, would say, ‘I’d rather be dead’. I also wonder how Chris can speak as he does without his emotions overwhelming him. He has a forthright media persona but this is also a family man who has watched his bold, brilliant, health-conscious dad regress so terribly.

“I find it really difficult at times,” he says. “I find that I’m getting better about it, but if I sit and think about my dad, and about how it is when I visit him…as I’m speaking to you now, I’m struggling.

“This was a strong, fit, funny man who people looked up to. As a teacher he had an eye for the rogues and liked to help them. It makes me so proud when I hear people talk about him. It would have been impossible to think this could happen to him.”

There is a small tremor of emotion in Chris’s voice, and this is because he has spoken again about his latest visit to Mike. “I’ve got an eight-year-old daughter who I take to see him,” he adds. “She’s always heard heroic stories of what her grandad was like, so it’s sad for her to see him in that manner.

“I’ll hold his hand and, when I go, I always make a point of never saying goodbye to him. I don’t want him to think I’m leaving. That maybe sounds a bit strange. But I just want him to know I’m there for him.”

You’re Better Than That! How to Fix Modern Football by Chris Sutton, published by Monoray, £14.99 www.octopusbooks.co.uk

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel