Norfolk Island is a dot in the South Pacific Ocean: five miles long and three miles wide, halfway between Australia and New Zealand.

But plenty of its 1,800 residents feel a close connection to Cumbria. Many are descended from Fletcher Christian of Mutiny on the Bounty fame, who spent his early life in the Cockermouth area.

They are appealing to the News & Star as part of their campaign to gain more independence from Australia.

An unusual request, they know. Unlikely to inspire politicians in Canberra to change their position, they know.

Part of their reason for making contact is just to tell Cumbrians that Norfolk Island exists: that 10,000 miles away are people who live and breathe because of a famous Cumbrian.

“We identify ourselves as more British than Australian,” says Matt Nola, an islander and a descendent of Christian. “God Save the Queen is still our national anthem. So much of our history, we feel, unites us with the Lake District.”

This story begins with Christian, a man who would go on to be portrayed on the cinema screen by Errol Flynn, Clark Gable, Marlon Brando and Mel Gibson.

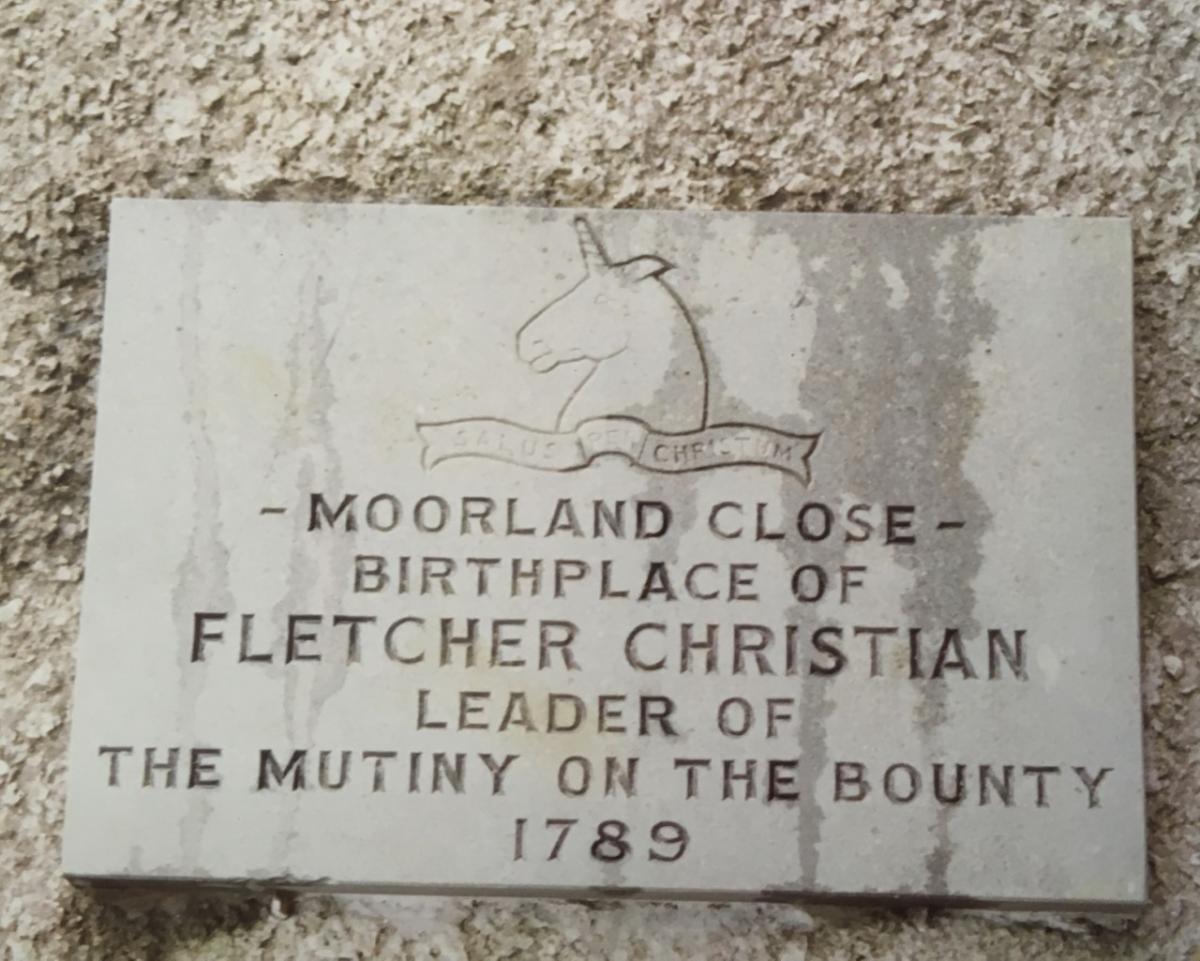

He was born in 1764 at Eaglesfield, three miles from Cockermouth. From the age of nine he spent seven years at the Cockermouth Free School and joined the Royal Navy as a cabin boy at 17.

He was master’s mate on HMS Bounty during Lieutenant William Bligh’s voyage to the Pacific island of Tahiti. Bounty arrived in October 1788 and spent five months there. The sailors were attracted to Tahiti’s idyllic lifestyle. Their mood darkened on the journey back, largely thanks to Bligh’s harsh treatment. Mutiny broke out, led by Christian. Eighteen mutineers set Bligh adrift in a small boat, along with those crew still loyal to him. Bligh and his men eventually made their way back to England.

Christian stopped briefly in Tahiti, where he married the daughter of a local chief. He and the remaining mutineers, plus six Tahitian men and 11 Tahitian women, then landed on uninhabited Pitcairn island.

Tensions apparently arose over the increasing extent to which the Europeans regarded the Tahitians as their property.

Survivors later claimed that in September 1793 the Tahitian men killed five of the mutineers, including Christian. He was reportedly shot and then butchered with an axe.

By the next year the Tahitian men were all dead, killed either by the widows of the murdered mutineers or by each other.

The surviving mutineers and their families lived peaceably on Pitcairn until it became too small for their growing population.

In 1856 their descendants - 194 of them - resettled on Norfolk Island; a deserted former British penal colony.

In 1914 the island was handed to Australia to administer. In 1979 it was granted limited self-government.

The island’s main industry is tourism. In 2010 financial problems, partly related to the global crash, led to Norfolk Island asking the Australian government for short-term assistance. This amounted to what islanders say was a small proportion of Norfolk’s annual budget.

After paying the money, Australia’s Parliament voted to abolish Norfolk Island’s legislative assembly. Major policies like tax and health care are now managed on the same basis as on mainland Australia. Most islanders voted against this and have been trying to loosen ties with Australia ever since.

Mary Christian-Bailey, 76, moved to the island from Australia at the age of 22 to be a teacher. She and her husband Bernie Christian-Bailey have five children.

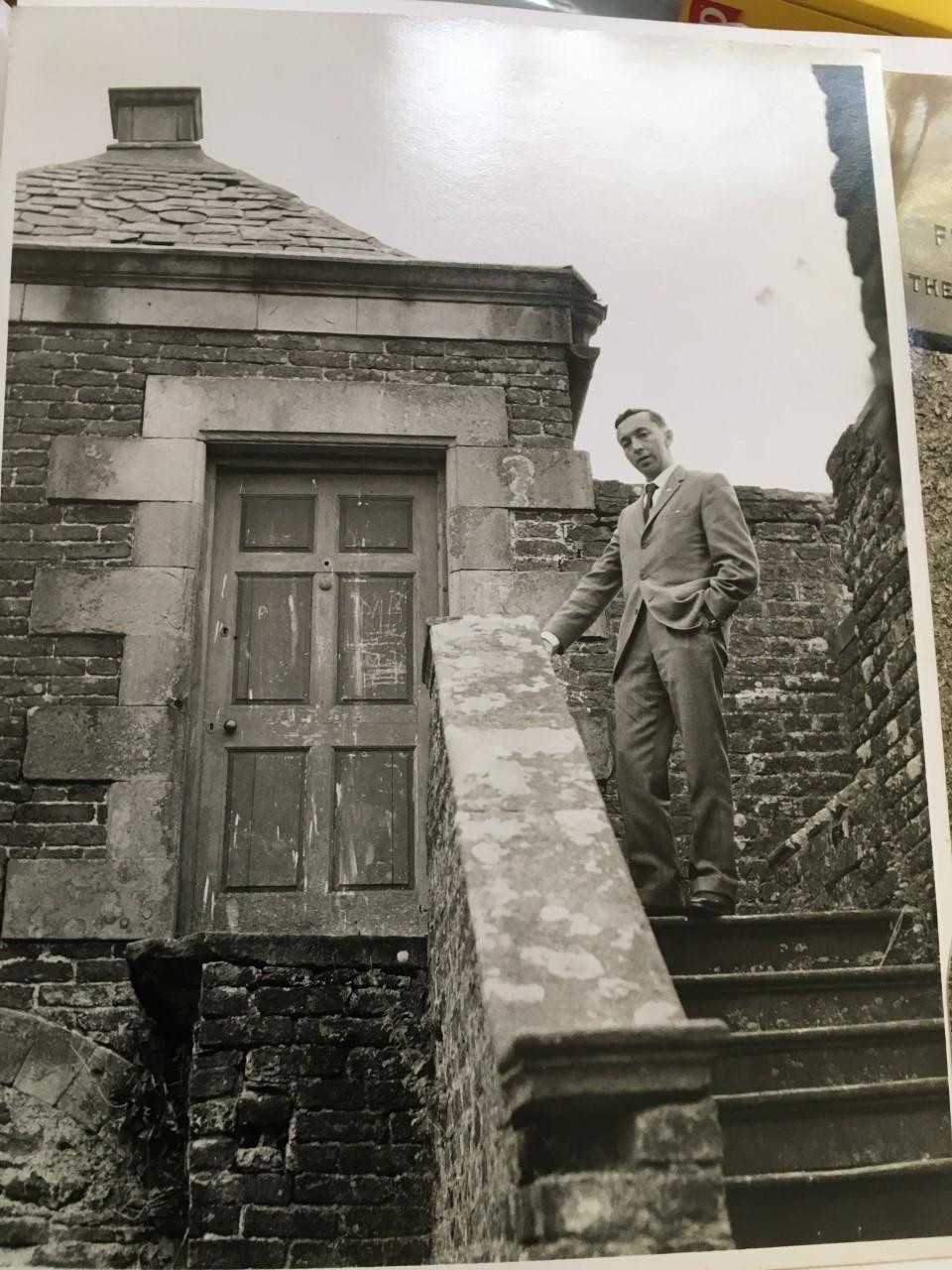

Bernie is a great-great-grandson of Fletcher Christian. In 1962 he became the first descendant to visit Cumberland, as it was then. Bernie, now 90, recalls being greeted warmly and taken around the district by a local newspaper reporter.

“I believe everyone made quite a fuss of him for being the first member of the Christian family to return to the area,” says Mary.

The trip included a visit to Moorland Close, the Christian family’s former home. Bernie arranged for a local stonemason to produce a plaque which was fixed to the house, with its owner’s permission.

Over the years Bernie has encouraged other Norfolk Islanders visiting Britain to include a trip to Cumbria.

Mary says that about half of islanders are descended from the mutineers, and many more have married into those families.

“People are extremely proud of their heritage. The Norfolk Island people feel like a separate people. Having been on Pitcairn for nearly 20 years before they were discovered, then onto Norfolk Island with no outside influence.”

This is why many islanders resent the extent to which Australia is now dictating what happens there.

“It wasn’t a huge amount of money,” she says of Australia’s financial support. “They put in a lot of conditions. It’s like blackmail in many ways.

“Where Norfolk Islanders feel it hardest is the denial of their identity and heritage. They’re just expected to be part of Australia and to be Australians.

“That’s pretty hard when you’re a people that’s looked after their own affairs for a couple of hundred years, that’s tried to deal with small, remote island problems in a small, remote island way. They want the right to work out their own solutions.

“The island is being subsidised in Canberra. But it’s being spent on bureaucracy and managers, on solutions to problems that don’t exist.

“New South Wales Department of Education spent an enormous amount of money at the school putting safety rails on verandahs and walkways that were only just off the ground. That’s New South Wales’ policy. No one bothered to think if it was necessary here.

“We never had land rates before. Now we have them. The system of family land that gets handed down to the next generation; people can’t afford to hand it down anymore. That goes against something that’s very important to people.

“Norfolk Islanders are independent-minded and extremely resourceful. They have to be when you live a long way from anywhere. It grieves people to see huge amounts of money being thrown at something that isn’t productive or necessary.

“The Falklands has the rights to the fisheries around its islands. Australia gets everything around Norfolk Island. Australia wants to work towards undermining the influence of the Pitcairn culture, to reinforce the claim that Norfolk Island is just part of Australia.”

Islanders have appealed to the United Nations to be recognised as a non-self-governing territory. These are territories governed by another country.

The UN says the interests of the people in these places are paramount and should be monitored.

Mary would like the UN to help Norfolk Island towards self-determination, “choosing what type of government we want. Whether to be attached to Australia like the Falklands is to Britain, or be more integrated, or be independent.”

Islanders have met British MPs. They hope that Britain’s relationship with Australia will have some influence.

The future is not the only uncertainty in this tale. Our view of Fletcher Christian - hero, villain or something in between? - is based on contrasting accounts from long ago. His volatile life has captured the imagination of legendary actors. His name lives on in popular culture, including the name of a Cockermouth pub.

Matt Nola says: “For certs, there was nothing glorious in the mutiny despite what Hollywood likes to portray.”

As well as “for certs”, Matt also says “the morrow” for tomorrow. Norfolk Island is a place apart in many ways. Very far from Cumbria, and very close.

n A petition calling for greater representation for Norfolk Islanders is on the change.org website.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel