For a small country, Ireland has always had a disproportionately large number of writers.

From Jonathan Swift via Oscar Wilde to James Joyce, WB Yeats and George Bernard Shaw to Seamus Heaney, Michael Longley and countless others, there are far more than you might expect.

Malcolm Carson could fit within that tradition, almost.

He was born in Cleethorpes in Lincolnshire but his father was from County Antrim, his mother was from Belfast and he spent some of his late teens in that city.

So when he mimics the Northern Irish accent he is note-perfect, unlike so many other English attempts at it. It can even make a Northern Irishman slightly homesick.

He can slip in and out of it with ease. In fact if he wanted to pretend to be an Irish writer, rather than a writer with Irish parentage, he could probably get away with it.

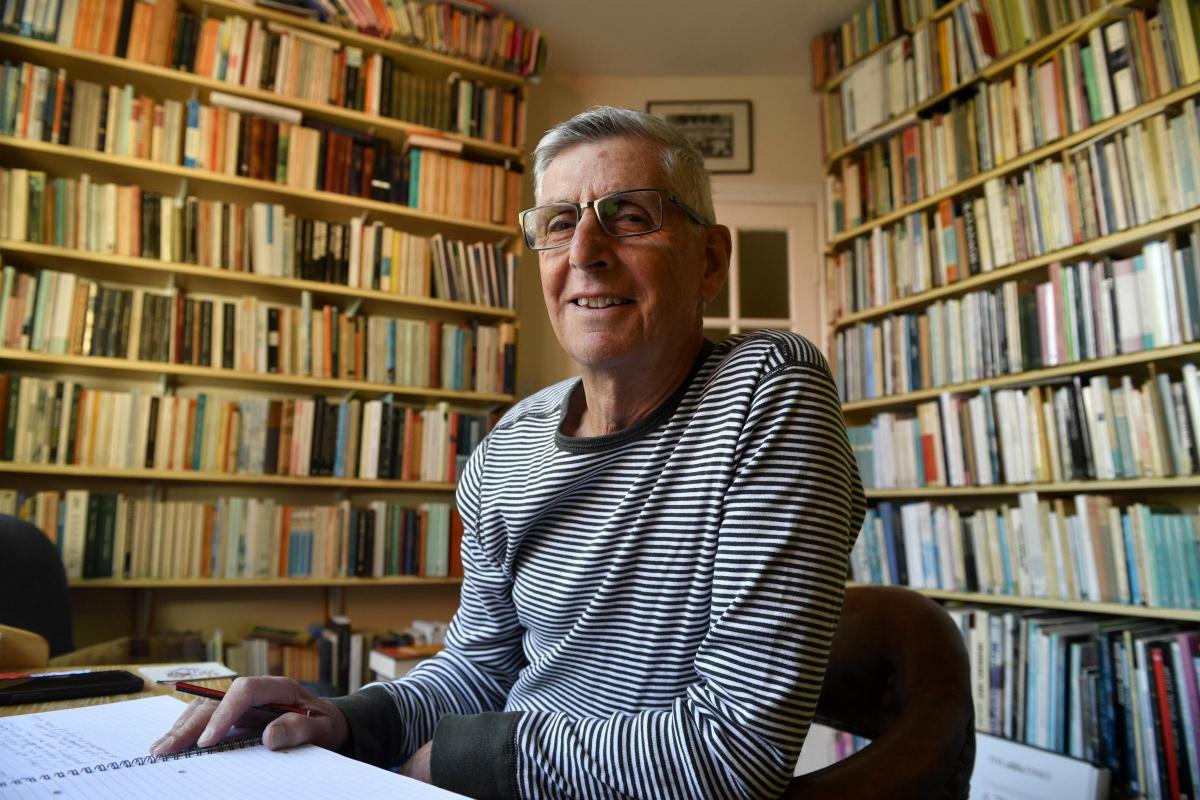

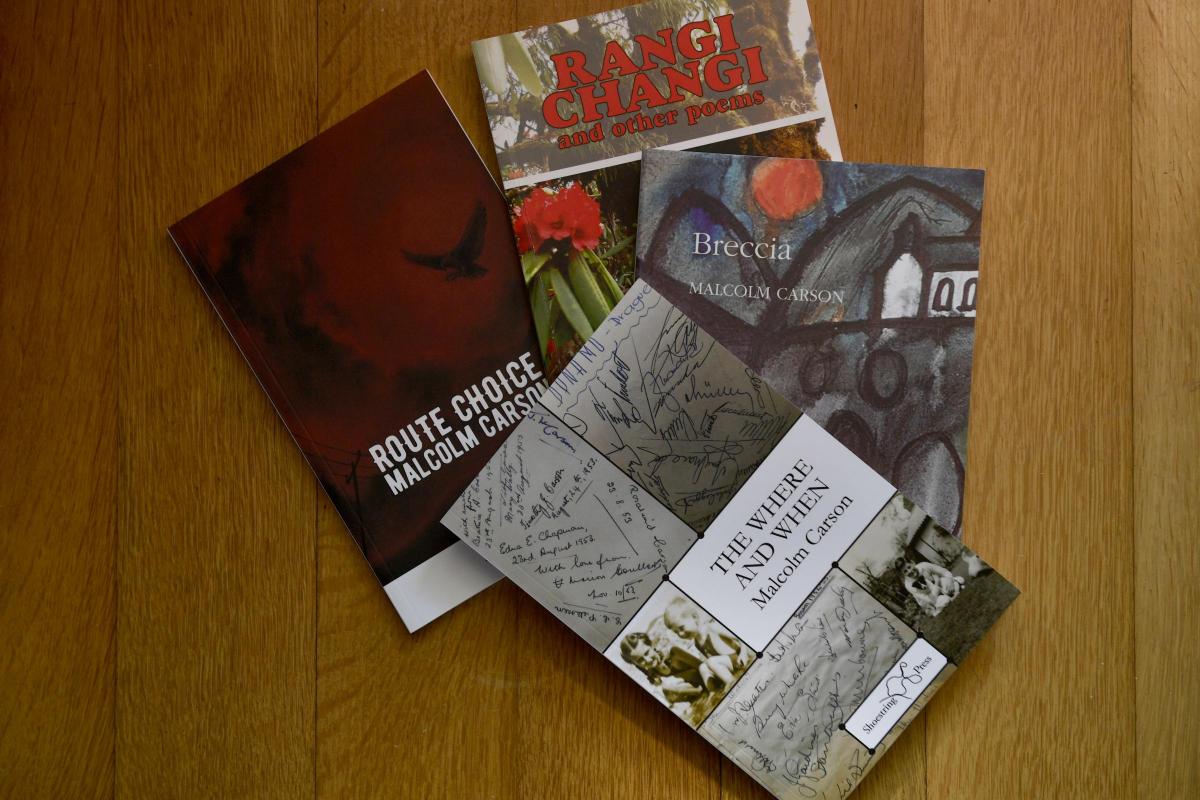

Yet Malcolm has lived in Carlisle for the past 28 years. He is the author of four collections of poems and will be reading from and signing copies of the latest, The Where and When, at Cakes and Ale café on Tuesday, June 11.

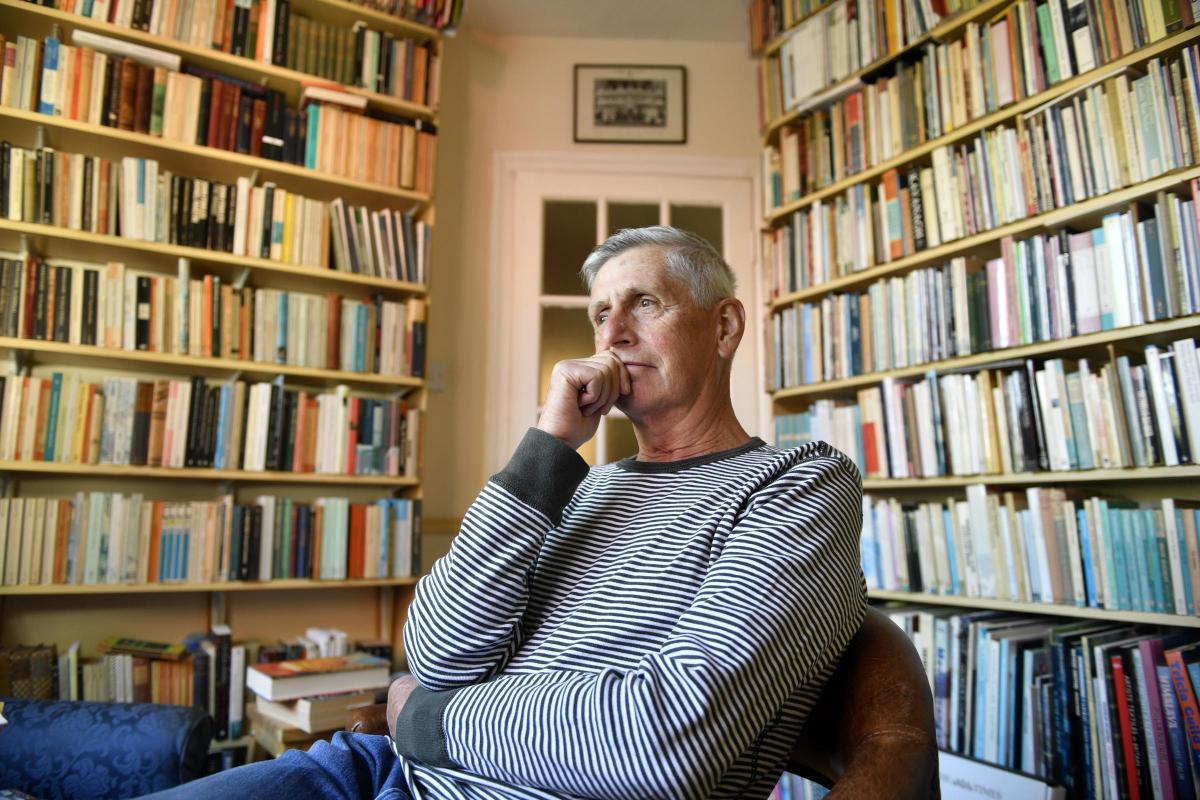

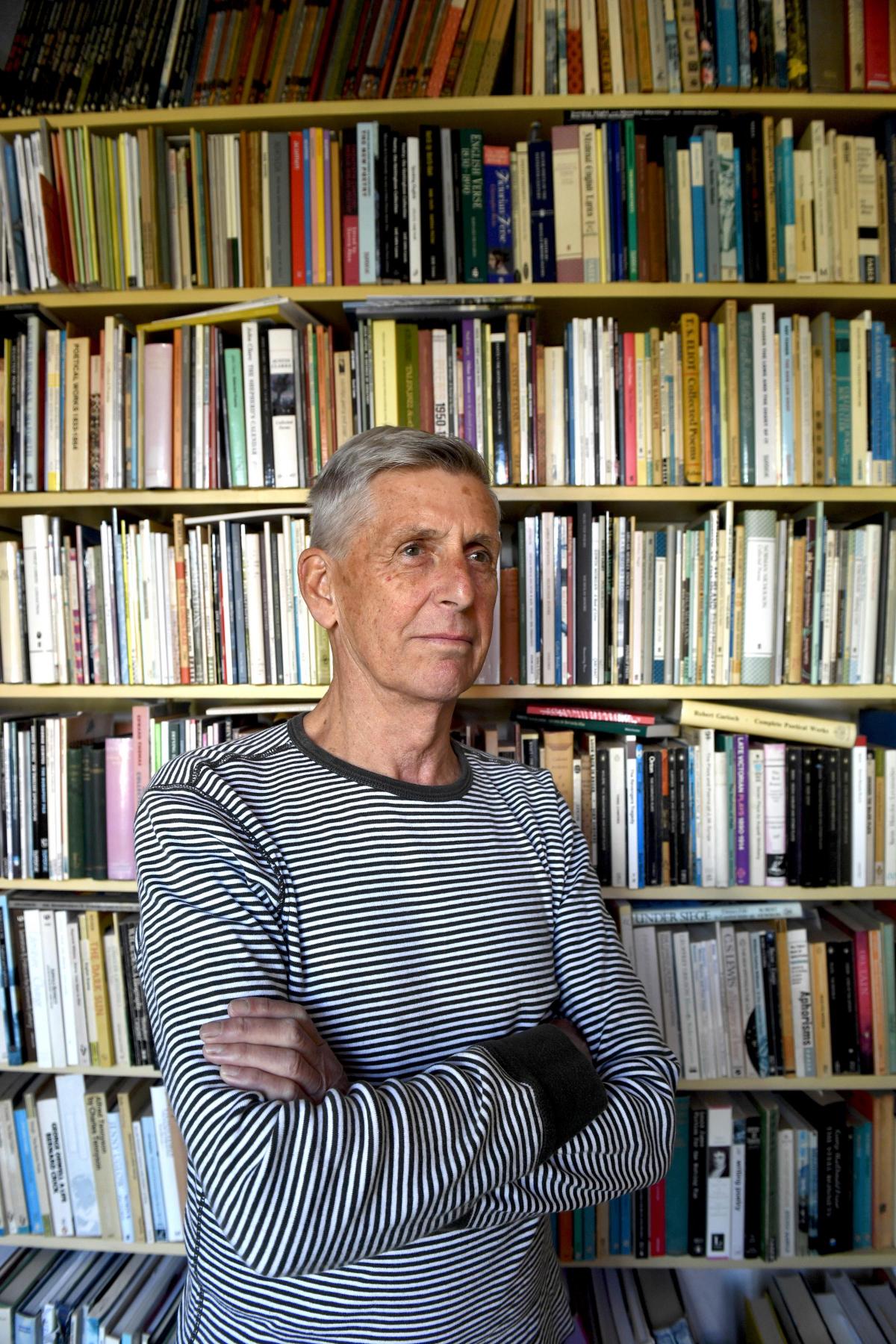

Some of us might imagine the typical poet as moody and dreamy, eyes lost in thought.

But Malcolm is engaged, talkative, friendly and self-deprecatingly humorous.

He does have a poet’s untidy, book-cluttered writing desk. But he had no interest in poetry when he was young.

His father was a doctor who had studied medicine in Belfast and Dublin and had a GP practice in Cleethorpes, and decided to move back to his homeland when he retired.

Malcolm won’t give his age, but moved to Northern Ireland with his family at the age of 16 “before it all kicked off” in the late 1960s.

He remembers vividly the culture shock that met him there.

He attended Campbell College, a large boys’ grammar school in the east of the city which, at least in those days, had a good reputation.

“Being an English boy in an Irish school was very odd,” he recalls. “It was the accent more than anything else.”

“Just saying my name in a flat Lincolnshire accent sounded like ‘Cahson’, not ‘Carrson’.”

So he changed his voice. “I had to learn to speak ‘morre like this herre,” he says, with the more distinct Rs of Irish accents.

“And going from a badly run grammar school in Cleethorpes to Campbell was a shock. My school in Cleethorpes was chaotic, wild.

“It had a terrible headmaster, there were fires in the classroom and so on.

“The pupils would be chucking toilet rolls around while the teacher was trying to talk about poetry. Campbell was totally different.”

Campbell College took and takes rugby very seriously and when it failed to reach the final of the inter-school rugby cup he remembers the stern, pompous warning from the headmaster in assembly.

“He said: ‘If you must go to the match, remember to remain aloof.’”

Religious observance of Sundays in Northern Ireland also took him by surprise.

“Everything closed, there was nothing to do except go to the park.

“But I had a whale of a time in Belfast. I loved it there.”

He was also a singer in an amateur band. “We’d play Eddie Cochrane, Buddy Holly and Roy Orbison, and charged a small amount for people to hear us, until the police shut it down.”

Malcolm took a wrong turn in his choice of A levels. “I did sciences – I don’t know why – and I failed wonderfully. I screwed up the whole lot.”

By then his parents had decided to move back to Lincolnshire, where most of their friends were, and Malcolm followed them.

He got a job as an auctioneer in a country auction house in Louth and says: “We sold everything. There were antiques, furniture, livestock, produce, everything. My first sale was a huge bag of carrots.

“I was terrific. I was fast and I got good prices.

“I’ll watch auctions on TV from time to time and they’re rubbish, they’re far too slow.

“The quicker you are, the better prices you’ll get. There’s a sense of urgency.”

It was while in Louth that he first really discovered poetry. “I was in a bookshop during my lunchtime and I picked up this book called The New Poetry.”

It featured the work of Ted Hughes, Philip Larkin, John Wain, Kingsley Amis, RS Thomas and Norman MacCaig among others.

“I bought it, took it back to the office and I was hooked.

“Then I started reading Shakespeare properly for the first time. My aim was to go to university and study English.”

He studied part-time for three more A levels, in English, French and Latin, and won a place at Nottingham University. Before taking it, however, there was more work to be done – driving tractors in the Lincolnshire countryside.

“It was muck spreading mostly. It was cold and wet, you’ve got diesel and cow muck on your hands, you’re eating your sandwiches in rat-infested barns.

“The people who were doing the ploughing got the newer tractors. We got old, beaten up ones.”

With more time before starting university he travelled through Europe, taking in Ireland, France, Italy, Greece, Yugoslavia and Spain. “I was going to go to Morocco but I ran out of money.”

Then there was a lot more work back home, during the pea season. “Lincolnshire fields are perfect for pea growing,” he explains. “People were working 16-hour shifts at Bird’s Eye.”

At university he developed a love of writers such as WB Yeats and James Joyce. He adds: “John Clare is one of my favourite poets, and I got to like TS Eliot.

“Sylvia Plath was a very good technician. And when she was good she was very, very good.

“It was then that I thought: ‘I’ll have a go at that.’ I wrote quite a bit at university and I edited the university poetry magazine for a couple of years.”

Afterwards he taught at a secondary school and then a further education college in Grimsby.

He married his wife Caroline in 1991 and took a job at Carlisle College and then at the University of Northumbria when it had a campus in Carlisle. Their three sons grew up here.

Writers are forever being asked where they get their ideas from – and invariably find it impossible to answer.

“I’ve no idea!” Malcolm says. “Sometimes I find myself thinking: ‘Where did that come from?’

“When something goes wrong you might think: ‘That could be a poem.’ For some people it can be therapy.

“I still write about things that happened a long time ago.”

The writing process, he adds, can be “very enjoyable and very rewarding. It can also be massively frustrating.”

And his advice to aspirant poets is: “Be self-critical. Stand back from your work.

“There are people who will read a poem straight off their phone. There’s nothing wrong with that in itself – but I wonder how many crossings out and revision have taken place.

“And look for musicality in your work. If there’s no musicality it’s chopped up prose.”

n Malcolm will be reading from The Where and When at Cakes and Ale in Castle Street on Tuesday, June 11 at 7.30pm. Signed copies will be on sale for £10. For more details call (01228) 529067.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here