Armed robberies do not tend to come with silver linings. In Mark Pringle’s case, there are two. Firstly: his robbery did not succeed. “That career definitely wasn’t for me,” he says. “It wasn’t organised crime. It was disorganised crime.”

A judge at Carlisle Crown Court agreed. He described the attempt by Mark and an accomplice to rob a Cumbrian Post Office in October 2010 as “almost entirely incompetent”.

Mark held an imitation pistol as the men demanded money from the postmaster. They fled empty-handed after just 22 seconds, leaving a trail of clues.

The crime’s farcical nature did not lessen its impact on the postmaster, who was described in court as “traumatised”.

Mark pleaded guilty and spent four years in prison. He had been brought to this state by cocaine addiction. It had already cost him hundreds of thousands of pounds, as well as his relationships with his two sons and their mother.

The second silver lining: Mark is now a walking cautionary tale. He is volunteering to dredge up a painful past for The Cumberland News in the hope that his story will show drug addicts that there is a way forward.

Mark has not used drugs for 18 months. Last year he set up a scaffolding business which is doing well.

Speaking from his home at Thursby, the 41-year-old appears humble and contrite. He knows that revealing things he is ashamed of could deter potential clients, but considers this a chance worth taking.

The robbery was intended to clear drug debts. “I entered that criminal world to support my habit,” says Mark. “I couldn’t hold a job down anymore. I was sleeping on friends’ couches. I owed thousands.

“It was solely my idea. I wouldn’t put the blame onto anybody. I just screened off the reality of what I was doing. The reality of terrifying somebody for money. It was solely about my needs.

“We walked in with a replica firearm. The guy was round the back of the shop. It was like panic stations. My accomplice tried to take the till. It was wired to the counter. It bounced back and made a mess. It was a case of just getting out of there. It was more shock than anything - we’d just committed an armed robbery.”

They dumped the pistol and drove back to Carlisle. Earlier that day Mark had left his name and address at a nearby garage when he couldn’t afford to pay for petrol. When they fled from the post office he and his accomplice left behind a bag which had their fingerprints on it.

Two weeks later Mark was driving in Carlisle when his car was blocked in by police who arrested him at gunpoint. What was he thinking? “Bloody hell. Now I know what that fella at the post office felt like.”

He says that being remanded in custody and then sentenced was almost a relief. “It was like an end to that time of my life. I thought ‘I’ll do the time, whatever time I get.’ I was willing to ride that out and thinking that gives me a clean slate.”

Mark spent two years in prison before being released on licence. But he slid back into addiction, broke his licence conditions by missing probation appointments, and was recalled to prison for another two years.

Even after being released a second time, Mark returned to cocaine. Only when he attended a Narcotics Anonymous meeting 18 months ago did things change.

“A friend had been on the programme. He said ‘Come along, you’ve got nothing to lose.’ I quickly realised I was attending three or four meetings a week and I wasn’t using.

“I was meeting people that were like me. They would tell their stories, things I could identify with. It gave me a little bit of hope. I don’t take life seriously. Those meetings were one thing I did take seriously.

“I haven’t used since going to the first meeting. In the early days it was a struggle. When you have Christmas and everybody’s out partying. Last summer with the World Cup and your pals are at the boozer doing whatever: difficult times. A few wobbly occasions.

“Your brain starts to tell you you’ve got control of this now. Your brain wants you to use. ‘Once isn’t going to hurt you...’ If that was the case I wouldn’t have had 20 years of problems.”

Mark describes cocaine addiction as “madness. This drug has caused me nothing but grief yet you still go back to it, like a friend who wishes you harm. The amount of money that I’ve wasted. The friendships that have been lost. The relationships that have been lost.

“My brain tells me all the good things about using cocaine and none of the bad things. The first couple of lines you take is good. You feel euphoric - conquer the world sort of thing. From an hour in it just becomes a chore.

“You’re on edge. Paranoid. It’s not a lot of fun. You can make stuff wrong in your head. You’re insecure in relationships. You think people are talking about you - it’s as real as you and me sitting here. As soon as your head’s cleared a bit you can see. ‘I don’t know how I got that idea in my head.’”

What was his lowest point? “Suicidal thoughts. I’m an optimistic person. But when you’ve damaged so many lives, you sometimes think it’s a big black hole and I don’t know if I can get out of it.

“I know a lot of friends who have committed suicide through cocaine use. I’ve used at their funerals. ‘It’s what he would have wanted.’ And the reason he’s in that box in the ground is because of that drug.”

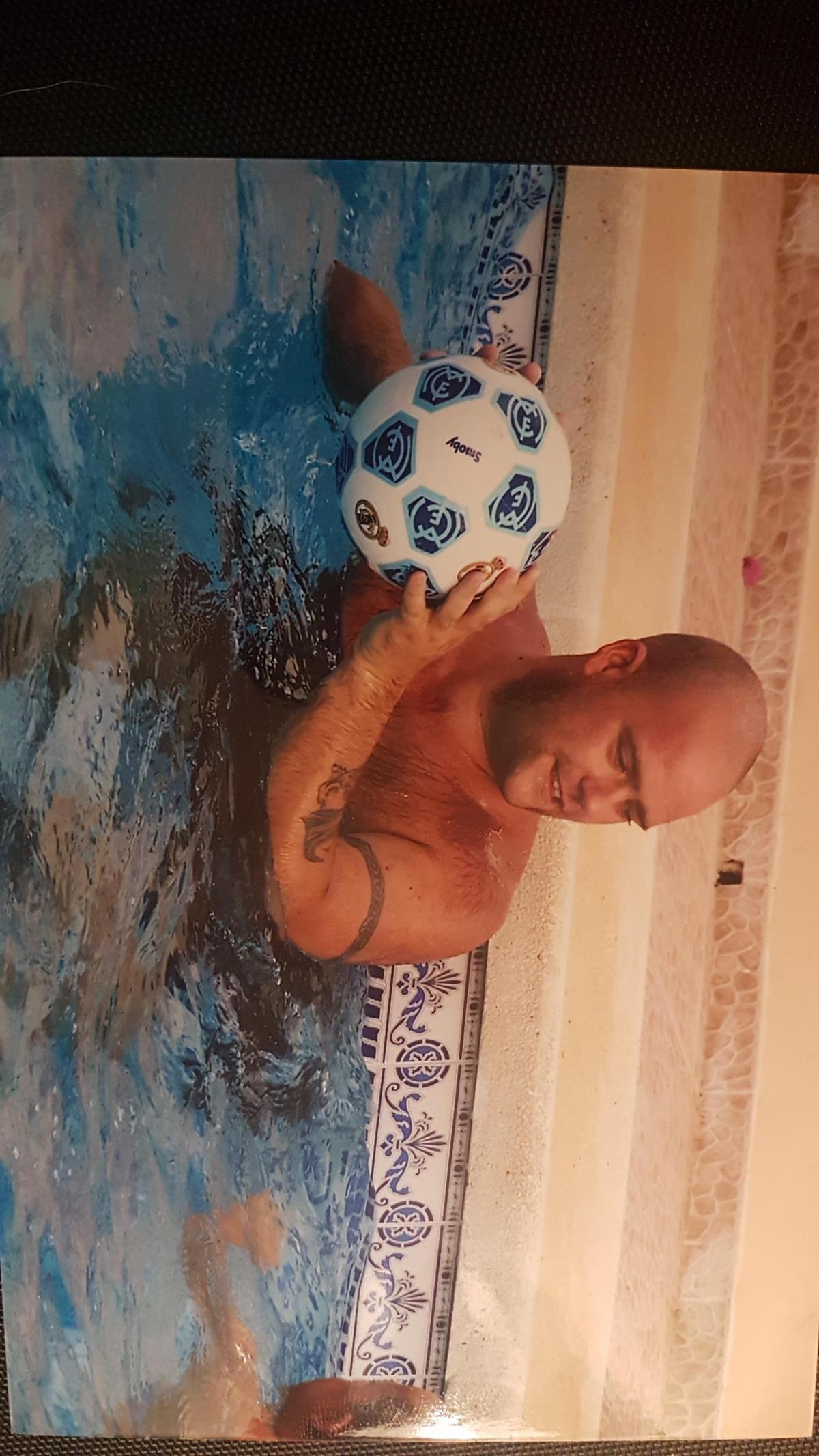

Mark grew up in the Belle Vue area of Carlisle, worked as a mechanic and moved to Bristol aged 20. He met his former partner there. They had two sons and moved to Spain. Their dream life included a house with a swimming pool.

“I ended up having a car hire business, two garages and a kebab shop. There were 26 people working for us.

“I’d dabbled before in the drugs scene. Nothing major. In Spain I think it was the lifestyle. Business meetings were all done in pubs. Drinking and drug use became quite intense. I was spending about £100 a day on cocaine. I would start in the morning and go on through the day. You can’t sleep. I blamed my problems on the stresses of work. But it was work that I’d created.

“The recession hit Spain in 2004. I ended up losing half a million quid. I lost everything. The majority was down to me. I split up with the kids’ mam. She didn’t know I was doing cocaine. I ended up telling her, just because I couldn’t keep the secret any longer.

“It answered a lot of questions that she couldn’t put her finger on. Money going missing. Benders: going out after work on Tuesday and turning back up at the weekend.

“With drugs they’re always your first priority rather than your business, relationships and kids.”

Back in Carlisle, Mark was still using cocaine while holding down a job as a mechanic. “I classed it as managing the situation. I was looking for the littlest excuse to get on it. A bad day at work. A good day at work.

“It’s the disease of addiction. It’s only the last couple of years I’ve learned about it. As a teenager growing up in Carlisle, cocaine wasn’t about. But I always seemed to be the last one standing at a party, the one that didn’t want to go home.

“People said ‘You seem to have this destruct button that you keep pressing.’ I couldn’t work it out until I got clean. You’re definitely born in that character. A lot of people I see at Narcotics Anonymous meetings have the same traits. We like to be liked. You carry that disease of addiction throughout your life.”

Mark says that Narcotics Anonymous emphasises taking one day at a time. Daring to look further ahead, he doesn’t know what it would take for him to return to drugs.

“Your worst day sober is better than your best day using. I’ve got members of my family back in my life. Helping other people stay off it is one of the things that keeps me off it.

“I have managed to help a couple of people. When newcomers come to the group I often give them my number for some support. If you can ring somebody and have a conversation or go for a coffee, sometimes that makes it easier not to use. It’s not just hooligans and council estates and all that. It’s solicitors and doctors.”

There are still times when Mark needs support. He hasn’t seen his sons, who are now in their late teens, since before he went to prison.

“That’s something that I’m working towards. The wrongs I’ve done to different people... I get frustrated and think ‘I’ve packed all that in now - you should forgive me.’

“When my ex-partner stopped me seeing my kids, I used that as an excuse to use. Any excuse. When I used to use, it blocked all the pain. Now you’ve got to deal with it head on. I’ve caused the mess so I can’t blame anybody else but me. It’s got to be me that sorts it out.”

Mark hasn’t contacted the postmaster he traumatised on that dark day eight years ago. “I thought that would be quite cheeky. He’s not going to forget the incident. I would have thought the last person he’d want to hear from or see is me.”

Mark is grateful to his partner Adele for sticking with him during the past four years. Six months ago he set up M&S Scaffolding with business partner Simon Lofthouse.

Mark wants addicts to see his story and realise that their lives can improve.

He admits to worrying that people who didn’t know about his past might treat him differently now, but he hopes for understanding.

“There’s not many people who couldn’t identify with a family member or somebody they know having used drugs,” he says.

Then he adds something which strikes at the heart of whether we believe people can change, and whether we can forgive: “I’m not that person anymore.”

n To contact Narcotics Anonymous visit http://ukna.org/

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here