One hundred years ago terms such as 'lunatic' and 'mad house' were commonplace in mental health treatment.

It shows how far we have come that these words are no longer socially acceptable - and will actually make many cringe.

A new exhibition, launching today, is taking a look back at Carlisle's famous mental institution - the city's Garlands Hospital.

"Secrets of the Asylum: 100 years of the Garland Hospital" gives a fascinating insight into life in the institution.

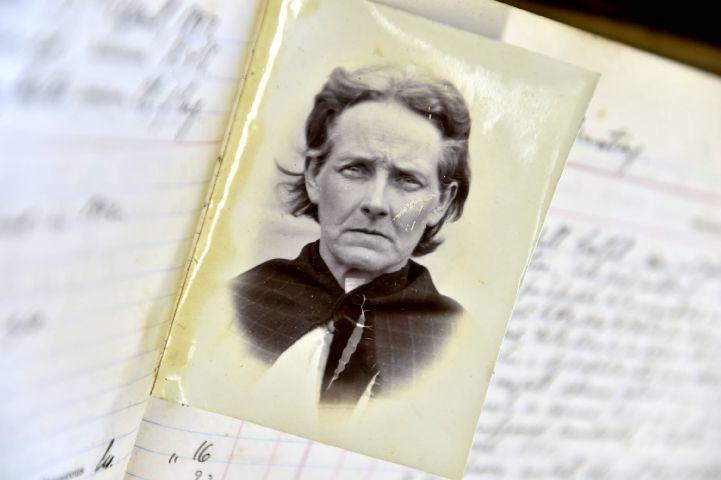

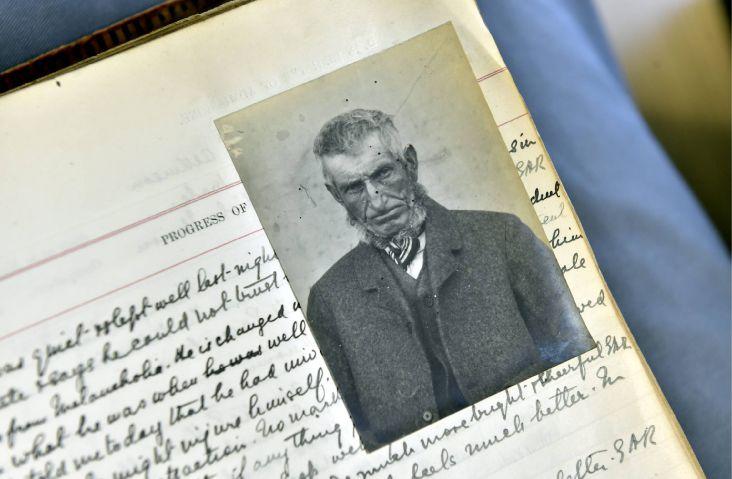

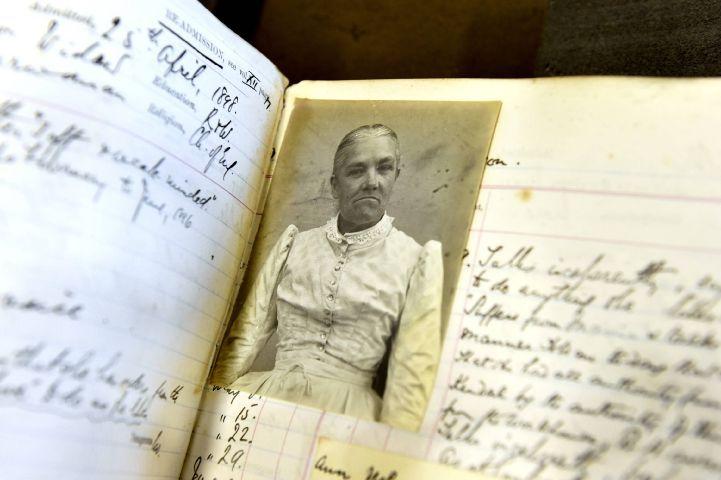

It will see some of the historic records made public for the first time, telling the stories of those who were treated there.

But as well as looking back at the past, it is also shining a fresh light on mental health stigma in the 21st century.

It shows how treatment has advanced in many ways, yet in contrast some of the older methods - such as spending time outdoors and keeping active - are now making a comeback.

The exhibition has seen teams from Cumbria County Council archives, public health, the Cumbria Partnership NHS Foundation Trust and Carlisle Eden Mind working together to bring it to fruition.

Cumbrian Phd student Cara Dobbing has led much of the research.

She said the Garlands Hospital was built in 1862 and was initially called the Cumberland and Westmorland Lunatic Asylum.

It started out with a capacity of 200. Within a year it had grown to 220, and by 1914 there were almost 900 patients.

It was the only mental institution in the area, taking people from all over Cumberland and Westmorland.

"This was a pauper institution. In the beginning it was for people who couldn't afford to pay for their own treatment," said Cara, who comes from Kirkby Stephen and studies at Leicester University.

As time went on, it became a specialist centre and started to admit private patients, money from which which helped keep it afloat.

The archives had full records of all the patients that received treatment at the Garlands, ranging from children as young as four to those in their eighties.

The majority of patients were receiving treatment for either mania or melancholy, which were common umbrella terms of the time.

Cara said there were a lot of women being treated for postnatal depression, while epilepsy was also seen as a mental health condition.

She said some of the records were quite upsetting, reading accounts of patients who had lost children, and seeing how they referred to people with learning disabilities as "idiots" or "feeble-minded".

One of those that has stuck with her was seeing a picture of someone who had Down's, but describing them as an idiot.

That said, much of her research actually contradicts popular opinion about what it was like in the asylum, or mad house as it was called then.

"The main thing that I found was that, when you mention the Garlands to people, there's this sense that it was a horrible place, quite brutal. But when you get into the records, you see that it wasn't.

"People also thought it was somewhere you went into and were there for life, but that wasn't true either. Just like today they had standards to uphold and were judged on their recovery rates.

"I just want to raise awareness of what actually went on. There is a very skewed view of it. Actually it was quite enlightened," she said.

Records show that some people were only there for a few months, though others stayed for 40 years. Many of these would otherwise have been in the workhouse, so they were much happier there.

Treatment options back then were limited, with the only medication available being sedatives. Patients were therefore encouraged to spend time outdoors, go for walks, work on the hospital farm and complete tasks that would give them a sense of purpose. There were also regular tea dances and even day trips.

Mental institutions of the past are often associated with the notorious Bedlam mad house in London or viewed as places where patients were left in isolation wearing straight jackets.

But Cara said the opposite was true of the Garlands.

"They had a system of non-restraint. It was generally only used to prevent them from harming themselves," she said.

"There is a restraint register and they had to write down why it was used, what method and for how long. There are some years when nobody was restrained, and sometimes only one or two patients."

Cara said Cumbria is lucky to have such well preserved records, with the more recent ones also include rare photographs from that era.

"When you look at other asylums, the records are not as detailed as this. They were pioneering in terms of monitoring each individual patient. The records contain so much background and history," she explained

However the records contain very few accounts from the patients themselves. Cara said there are some letters, but these were only really kept if they were evidence of a person's delusions.

"There are some snippets about the patients, such as 'she says she is content and happy to remain here' or 'he was happy to sit in his favourite chair' but that's about it. None in their own words," she said.

Richard Thwaites, clinical director of Cumbria's First Step mental health service, said that the records show how much the approach to mental health treatment changed, as has the terminology.

"Nowadays, the majority of these people wouldn't go anywhere near an inpatient unit. They would be treated in the community," he explained.

To put that into context, at its height the Garlands had 900 patients, when there are now just over 100 inpatient beds for the whole county.

Yet in other ways, he said the treatments have gone full circle - with creative and outdoor activities again playing a big part in helping people tackle mental illness and boost general wellbeing.

He compared the Garlands' farm, where patients worked on the land as part of their recovery, to growing projects happening in Cumbria today.

Richard said that mental health is no longer as taboo as it was then, and this research project shows how much has changed.

"For me, this is fascinating. We need to see what's gone before so we learn from it and don't make the same mistakes.

"Growing up in Carlisle, people used to talk about the Garlands in a derogatory way. Now, with all the new homes that have been built up there, it's quite a prestigious address, with some houses are less than 100 metres from some of the wards. That shows there's definitely been a shift, but there's still quite a long way to go," he added.

Richard feels there is one glaring admission - the stories of the patients themselves - and he would have liked to have been able to hear those to prove that there really was no brutality or abuse.

Cumbria's public health director, Colin Cox, said that when the Garlands was founded, mental illness was hidden away in an asylum.

He said it is encouraging to see people now being far more accepting and talking more openly, and he hopes the exhibition will help to open peoples' eyes even further and, in turn, reduce the stigma.

"The interesting thing about this exhibition is to compare and contrast. To look at how we have treated people in the past and how we are treating people today, from a social perspective," he said.

"Mental health is not something that's gone away. It's becoming more and more important, and people are more aware. Roughly a quarter of people will experience mental illness. That's a lot," he said.

The exhibition is being formally launched this afternoon at Harraby Community Theatre, between 1pm and 4pm.

Michael Stephens, Cumbria County Council archivist, explained that health records are only confidential for someone's lifetime.

After 100 years, the rules relax and allow historians and the wider public to gain access via the official archives - making this exhibition possible.

As well as giving people a unique insight into the Garlands history, the team also hope it will raise awareness of the county archives and the type of information available to the general public.

Although the records are publicly available, the team have decided to withhold full names from the exhibition itself.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here