After a move to play in America had fallen through in 2006, there was nothing for a couple of months. I thought I’d be happy with that – happy to drift along without the pressure of another comeback.

I’d stay at home, with our new baby, Minnie, play more golf and try to enjoy life for what it was.

I assumed that it would bring me a little bit of happiness and, to begin with, it did. I was relieved to be away from it again. But doing nothing can’t keep you happy for long.

As the weeks passed, I started to get bored. I got out of bed knowing that I had no purpose in life.

I wasn’t keeping myself busy with anything that you could call a focus. I didn’t want to play and at this stage I had no urge to try to be a coach.

When you have time to kill and nothing to kill it with, you torment yourself in different ways. At home, little things started to nag.

That stain on the carpet wasn’t there before. Where did that come from? Who put that there? And what’s that – who put that mark on the wall? Minnie’s toy shouldn’t be left out like that. Can we not put things away? Is there any chance we can look after the place?

Tiny things, trivial things that I never noticed when I was happy and playing – now I couldn’t take my eyes off them. They wound me up, made me irritable. The monotony was awful.

Come September, there was an escape. A call from James Fletcher, the News Of The World journalist I’d entrusted with the news of my departure from Blackburn Rovers. Sam Allardyce had been in touch with him and had suggested that if I ever wanted to go back in to another of my previous clubs Bolton and train – use the facilities, keep ticking over – I was more than welcome.

It was something else to do, so I took up the offer.

It was strange being back at Bolton, but I realised I’d missed the club environment. I threw myself into training without any real worries.

In one session, we were required to do sprints which were measured by lasers. I whipped through them and was later told my times had been the quickest in the squad.

I was never the fastest player, so that was something. Bolton had just signed Nicolas Anelka, who was known for his pace throughout a career at many top clubs, and when we teamed up in five-a-sides, we ripped it up.

Later Anelka’s agent called Barry, my father-in-law who was also by now representing me. He could not have been more complimentary about how I had performed in training.

Part of me wondered if this was an attempt to butter me up, to add him to his client list, but that was never going to be on my agenda.

I was, ultimately, happy just going into Bolton and going home again without any further demands. No contract, no expectation, no pressure. Not yet.

Eventually there was talk that it might come to something with the club. The thought troubled me. I couldn’t go through with it.

One day I left the training ground and didn’t go back.

More aimless months, more monotony, more wasting away. Then, in July 2007 – another invitation, this one from the past. A call from Neil Dalton, the physio at Carlisle. Was I up to much, and did I fancy coming up to join in pre-season training? The door was open if I did.

I grabbed my boots and drove towards the M6.

Going back to Carlisle was a comforting thought, but not necessarily because of the football. It was a chance to go home, see Mum and Dad, my brother and sister, and some friends.

Back to Wetheral. A change of scenery. A chance to escape the mundane for a while.

At Brunton Park I was reassured by some familiar faces. Dolly was there, so was David Wilkes, and so was Eric Kinder, the youth-team manager who had been at Blackburn for many years before moving to Cumbria. “What the hell are you doing here?” he asked with a big smile.

I then met Neil McDonald, the manager.

“Thanks for letting me come and keep fit,” I said. “I’m happy just to train.”

Neil was an excellent coach, and pre-season training was very snappy. Carlisle had a decent young group of players who had come off a promising season in League One. Although I hadn’t trained with a club for months, I still felt fit and sharp and it was good to be part of a squad again.

I suppose it was inevitable that the local media would pick up on the fact I was back. I was photographed on the training ground and the picture was front-page news.

Carlisle, two years earlier, had helped turn around the career of Michael Bridges, who had come to the club after a rotten run of injuries. Could they do the same for me?

If that was their plan, it certainly wasn’t mine. I was filling time, nothing more – there in body but not really in mind.

I trained for a few days, dragged it out, then picked up a problem with my toe. The club sent me to a chiropodist, then I came back and trained some more.

The first pre-season friendlies were on the way, and Neil told the media that he would have a chat with me to see if I fancied playing in the first of them, against Kendal.

It didn’t get that far. It was Carlisle, and it was home, but I couldn’t do it, wouldn’t allow myself to.

After a week or so, I packed my things and went home. Initially, there was some confusion at Carlisle about where I’d gone, and Neil said he was disappointed it hadn’t led to anything.

Maybe I hadn’t made it clear enough that I’d never been looking for a contract. Maybe, like all the others, he thought he could tap into what I used to be. He had the same chance as the rest of them.

I knew that the people at Carlisle would have rallied behind me. But I also knew they’d have had questions.

“What happened to him?”

“Why has he ended up here?”

“He used to be great. Where did it all go wrong?”

How would I have explained to them that my bubble had burst, that I was afraid to take the plunge again – that, no matter how I looked and played, it just didn’t feel the same any more?

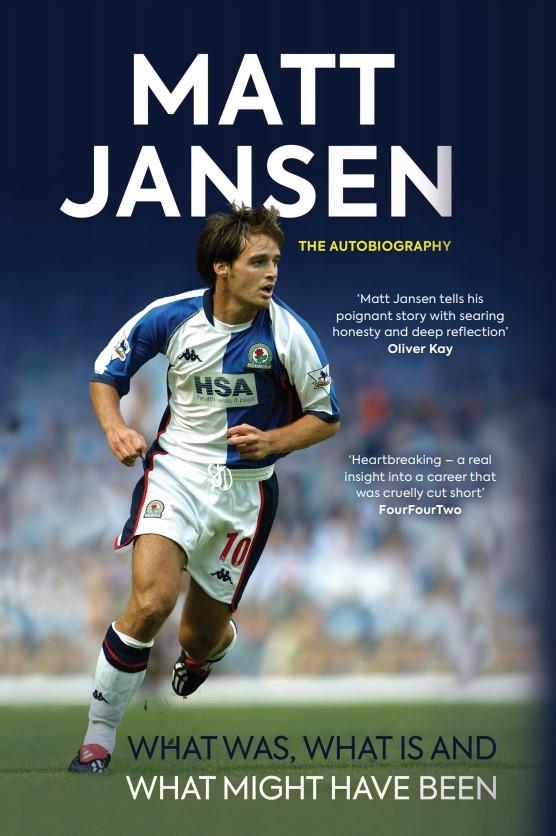

*Matt Jansen, the Autobiography: What Was, What Is and What Might Have Been is published by Polaris (£18.99)

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here