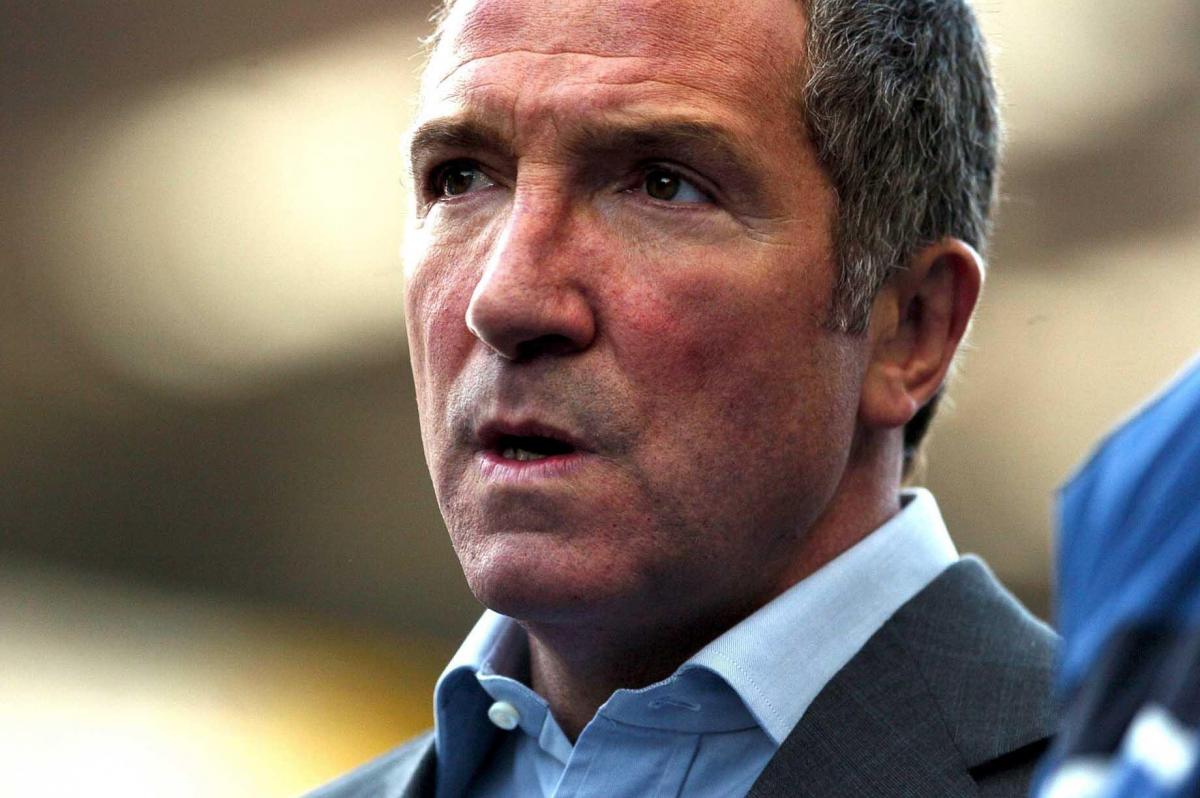

There was one more game for Blackburn Rovers in the 2002/3 Premier League season. If we won at Tottenham, it would mean qualification for the UEFA Cup. I was on the bench and watched as we built a 4–0 lead before manager Graeme Souness put me on for the closing stages.

“How long’s left, ref?” I asked.

“Another seven minutes.”

That long?

I was desperate for it to be over before it had started.

That summer, I then walked into a new problem: I started to forget about the torture of the previous months when I had struggled to regain my old feeling of invincibility after the accident.

As May slipped into June, I deceived myself into thinking that my problems were over. The truth was, I had merely put them into storage.

Away from football for the summer, I wasn’t going home anxious from a bad day’s training. I wasn’t standing under the dressing room showers asking myself why I wasn’t feeling the same. I wasn’t tossing and turning in bed quite so much. I was probably a better person to be around.

I conned myself that I was okay, and that next season, after a bit of rest, things would be fine.

We went to America for a pre-season tour, and that also seemed to convince Souness that I’d returned a different player. It was a fairly relaxed trip, with a bit of golf, a couple of nights on the beer and a game against DC United in Washington that passed without any problems.

I actually did okay in the friendly, but it was low-key, with barely any Rovers fans there.

Souness later said my form had been one of the highlights of our pre-season, and he put me in the starting line-up for our first few games of the new Premier League campaign.

I scored in our second match, against Bolton, but I didn’t feel like I was there yet.

I felt thousands of eyes on me, wondering who this lesser version of Matt Jansen was, and the vicious circle resumed.

By September, I was really struggling again and it made no difference to me at all when, against Liverpool at Ewood Park, I scored a goal that, to anyone else, must have appeared extraordinary.

Eight minutes had gone when the ball fell to me 25 yards from goal. Jamie Carragher, one of the country’s most determined defenders, was closing in from the right.

Approaching the D, I dinked the ball over his head, then wrong-footed him again as I shifted it back inside before smashing it home left-footed.

The ground went bananas and I ran off to celebrate. But I didn’t feel excited, or joyful. My expression was strained because I was closer to anger than jubilation.

What’s wrong with me? How did I do that? Why can’t I keep doing that?

Once again, I had no idea how it had happened. This time it was worse, because this was on the big stage, and the passing of nearly a year hadn’t made things any different.

It was a goal born of fear. I’d felt completely out of control.

From there, I went in and out of the side for a couple of months: dropped when I shouldn’t have been, playing when I had no right to be anywhere near the side. These were my own thoughts – I had no idea what Souness or anyone else was seeing.

I had no idea if or when it would all come back to me. I’d tried all sorts – going on loan, antidepressants, running myself silly, the occasional prayer – and nothing had worked.

I became depressed again and progressively found that the only thing I could rely on to give me any sort of relief was a beer. I got into the habit, whether at home or with a couple of the lads, of knocking a couple back. It took my mind off the problems and helped me hide away.

The temptation to hole up in the apartment with Lucy, switch on the telly and have a few drinks became overwhelming and, increasingly, I started to look forward to days off, because I knew I could have a little binge.

It’s no way to live your life, and I can’t think how it must have been for Lucy. My medical notes around this time indicate I was ‘very low and depressed’ and even entertaining ‘some self-harm thoughts’, and I suppose what happened in this period fits both theories.

I was in the apartment, on my own, after another day’s training that had confirmed to me that I was still all over the place.

I reached into the fridge for a bottle of beer and flicked off the cap. I glugged it down and went back for another.

I felt desperate. I was drinking to block it all out, and I knew it. I sat down, stared into space and realised that I was crying.

After a couple more bottles, I began pacing around. I wanted it all to stop. I paused and opened one of the kitchen cupboards. I knew what I was looking for and it didn’t take me long to find it: a box of Anadin Extra.

I removed the sleeve from the box and pressed out the pills, one by one. I threw the lot into my mouth and swilled them down with lager.

I don’t remember exactly how many there were. There could have been eight, there could have been a full pack, there might even have been a second pack. I wasn’t counting. I was past caring.

Someone will find me. They’ll take me to hospital. I’ll be fine.

I had a few more beers, to help get me off to sleep, and eventually stumbled to bed. When I opened my eyes, it was morning. My mouth was dry but everything else was normal. I got up, walked into the kitchen and saw an empty box on the counter.

I cursed myself.

Just as hangovers never troubled me, it turned out I was also resistant to a gutful of Anadins. Great.

I wouldn’t categorise it as a suicide attempt. I wasn’t thinking as clearly as that. It certainly wasn’t planned, and I didn’t have any real idea what would happen.

I just wanted whatever was eating me alive to stop for a while. I should have been relieved that the pills hadn’t done any damage, but I knew it had been another cry for help that nobody had heard.

* Tomorrow: Battles, bruises and brilliance with Carlisle United

Matt Jansen, The Autobiography: What Was, What Is and What Might Have Been is published by Polaris (£18.99).

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel