"I couldn’t believe that could happen in football,” says Mick Wadsworth as, nearly 25 years on, he remembers the deluge of letters and cards he received upon walking away from Carlisle United. Wadsworth, the director of coaching, left for Norwich a few months after overseeing a stunning and historic season at Brunton Park. It was an awkward and regretted parting both for Wadsworth and the many supporters who had grown to revere him.

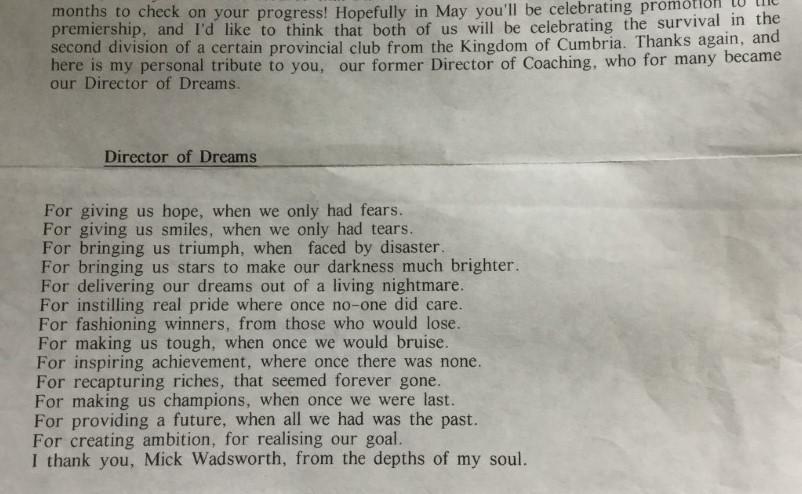

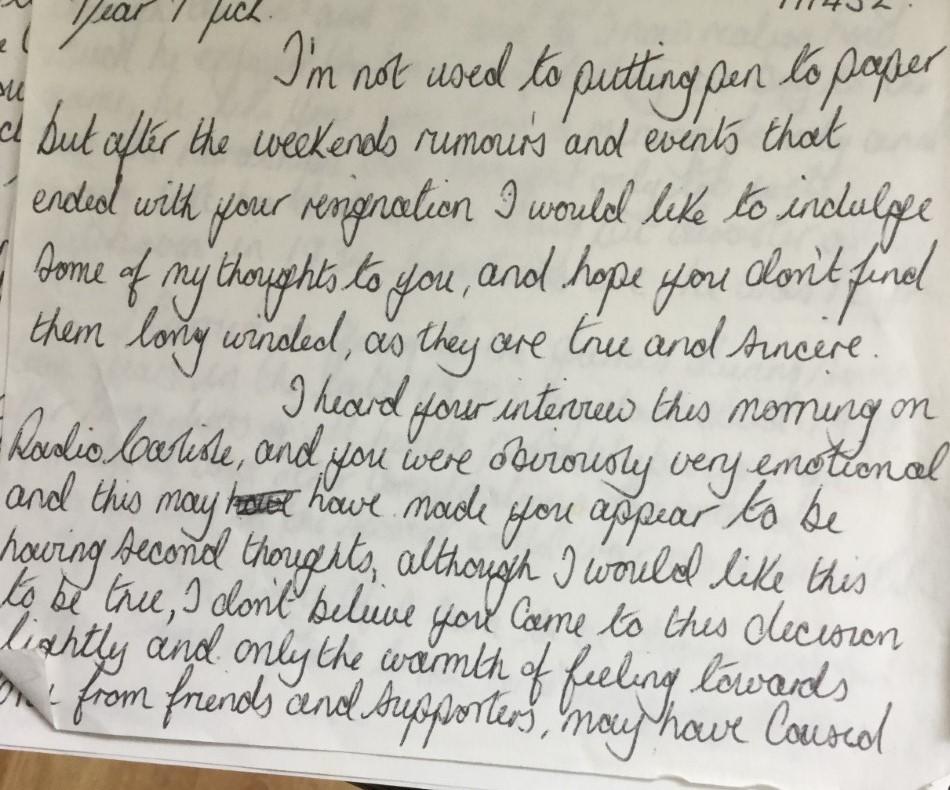

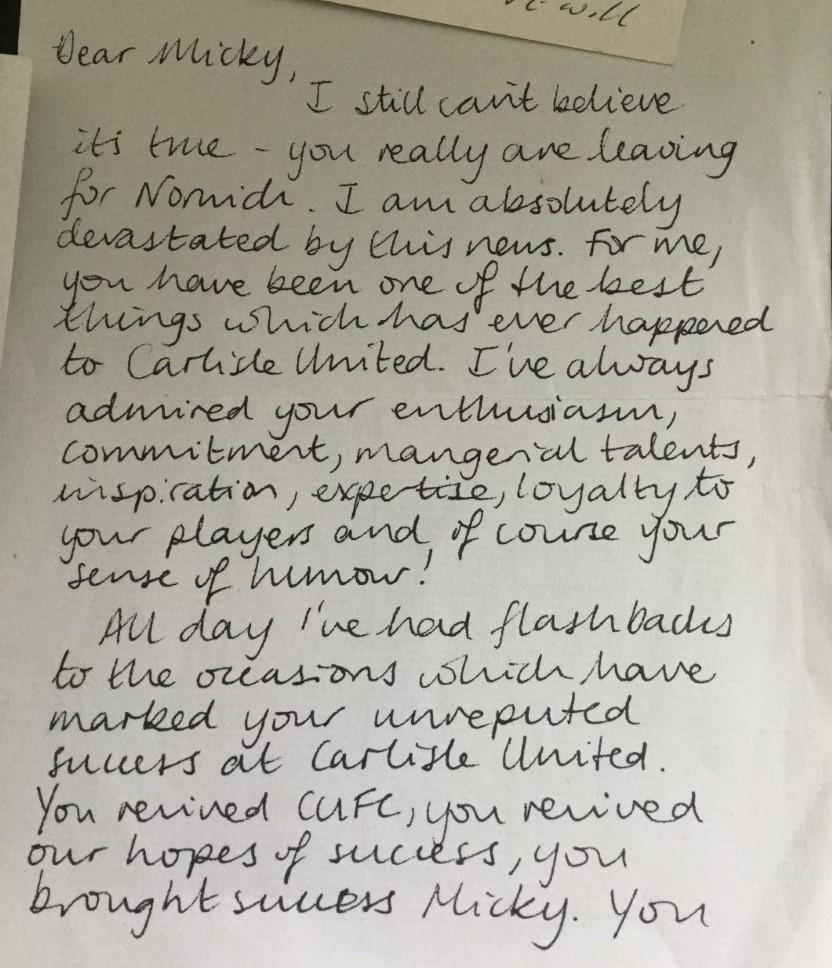

After our interview, Wadsworth posted to me a few of the heartfelt messages that United fans sent him in January 1996. Words of sorrow, disbelief and gratitude tumbled out of a large brown envelope. One man even wrote Wadsworth a poem.

“It hasn’t happened since,” laughs the 69-year-old, thinking of his vast career of many more managerial and coaching roles. “But it was amazing, the amount of mail I got. It was this pouring-out of emotion…it was gut-wrenching.”

Wadsworth keeps the cards and letters in a folder at home and has sifted through them occasionally over the last quarter of a century. “Not so much for affirmations of anything, other than it just being nice that people cared.”

The reason they cared, and still do, is that Wadsworth was central to one of United’s most exhilarating campaigns. 1994/5 brought the Division Three title with 91 points and was accompanied by the club’s first visit to Wembley, where they dramatically lost the Auto-Windscreens Shield final in golden-goal extra-time to Birmingham in front of 76,663 fans.

Wadsworth and many of his players had intended to reconvene this spring, but the Covid-19 outbreak curtailed a reunion which will hopefully be rearranged. A sell-out night had been anticipated, for it was one of United’s most fondly-remembered times. “It was a magical couple of years in my life, not just my career,” says Wadsworth, who was in charge from 1993 to early ‘96. “The sad thing is, you don’t enjoy the good periods as much as you should when it’s happening. The game eats you up and you’re always thinking about what you can do next. I probably learned that as I got older. But nonetheless, it was a great time. We had a ball.”

Wadsworth was appointed by the flamboyant Michael Knighton at a time United were creeping out of a barren period. A tough start was followed by a gallop to the play-offs as Wadsworth, assisted by Mervyn Day, aligned signings such as Rod Thomas to the best of what he inherited, like Dean Walling, Tony Gallimore and Simon Davey.

“The first few months were tough, but I found a lot of positivity, because he [Knighton] generated that,” Wadsworth says. “Michael had a great front, good oratory skills and presented himself very well, by and large. He was never negative. I’ve worked for some chairman who, when you lose, it’s like the end of the world. But Michael was really good that way.”

Carlisle broke their transfer record in the autumn of 1994, signing David Reeves from Notts County for £121,000. “I thought that was a magic moment. Reevesy was infectious, apart from being a bloody good centre-forward and great in the dressing room. To this day he’s a very, very good friend. A terrific signing. That kicked us on no doubt.”

Wadsworth also says it is his “proudest thing” that he gave debuts to more than 90 young players during his coaching career. At Carlisle he introduced a number from David Wilkes’ productive youth set-up, such as the goalkeeper Tony Caig, the biting midfielder Richard Prokas and the supremely confident Paul Murray. Others, such as Jeff Thorpe and Darren Edmondson, were already established and the likes of Matt Jansen, Rory Delap, Lee Peacock and Tony Hopper would flourish later.

He also brought in experience, like Joe Joyce and the centre-half Peter Valentine, and Carlisle got to the brink of Wembley in 1994, losing an epic Autoglass Trophy northern final against Huddersfield. “Huddersfield was funny,” Wadsworth chuckles, “because we left the chairman at their ground. We got beat down there [4-1 in the first leg] and everyone was on the bus at the allotted time, but Michael was still in the boardroom. I said to [driver] Colin Titterington, ‘Let’s go’. I don’t know how I kept my job after that…”

After losing to Wycombe in the play-offs, Wadsworth primed United with the experience of David Currie, the long-haired, enigmatic attacker, and the illustrious ex-Everton defender Derek Mountfield. “I just saw Derek on the list of available players, which I couldn’t believe. I thought we’d never get him. But I talked to him and he liked what I was saying.

“I’d watched a lot of Everton in the 80s, through working for the FA and living near Merseyside, and I knew a lot about him as a player. His physical condition wasn’t perfect – bad ankle, bad knee, sometimes had to wrap him up in cotton wool and say, ‘See you on Friday, Derek’ – but totally dependable as a player. I remember in one pre-season game digging Mervyn in the ribs, saying, ‘He’s not picking up, Merv, he’s nowhere near the centre-forward’. But the ball kept coming in and Derek kept heading it. After about 10 minutes I worked it out. ‘He knows what he’s doing. I’ll shut up’.”

Currie was just as influential. “I’d worked with him at Barnsley and always liked his ability. He could do things that were unexpected. He was overweight when he came in and we had to work like hell with him – he didn’t particularly like running around too much. But we got him in good nick and he did brilliantly. Adding him to Reeves and Thomas gave us a front three that had a bit of everything.”

United quickly hit the front of Division Three in 1994/5 and embarked on long unbeaten runs, where Carlisle’s vibrant, streetwise team was supplemented by a young midfield sentry. “Richard Prokas was a revelation,” Wadsworth says. “I’d watched him in training and thought, ‘He’s just efficient’. Didn’t lose the ball, tough as nails, could break up the play and allowed our other midfielders to attack.

“People talked about Claude Makelele as if it was a modern invention. Richard was the quintessential holding midfield player. He played early on at Torquay and hardly missed a game. It was just great getting those kids in the team.”

Murray, who would go on to accompany Wadsworth at several future clubs, was also eagerly in the wings. “There was one occasion [at Carlisle] where Muzza was on the bench, constantly at me to put him on,” Wadsworth smiles. “You know what he was like. Anyway, after about 75 minutes I told him to get ready. He sorted out his tie-ups and his pads, and when he took off his tracksuit top he had no shirt on – he’d left it in the dressing room. ‘You’d better go and get it,’ I said, but when he reappeared I decided not to put him on. ‘You won’t do that again in a hurry’.

“I’d forgotten about that, but don’t worry, Muzza has reminded me since…”

United showed brilliant spirit in adversity when substitute Thorpe flashed in two late goals for a 3-2 win at Scunthorpe, while other occasions were consummate, such as a 3-0 festive win over Bury when many fans were locked out of a packed Brunton Park. Reeves was voracious and in the spring Wadsworth replaced Preston-bound Davey with the £100,000 midfielder Steve Hayward – also adding the mercurial, ample figure of Warren Aspinall.

“I’d known Warren as a young player when I worked with England’s youth teams. He’d had his big moves to Everton and Villa and now he was at Bournemouth. Mel Machin, a dear friend, rung me up and said, ‘Do you want him? You can have him for nowt. I can’t deal with him. He’s mad’. I said, ‘Yeah, I’ll have a go’. I thought he was a good player, and the lads were so strong, they wouldn’t take anything from anyone who tried to kick against what we were doing.

“Yes, Warren was a handful – I remember throwing a cup at him at Chester and it whistled past his ear – but I liked him.”

On the road, United were a distinctive sight in their green, red and white striped away kit which itself became legendary. “Matchwinner brought some stuff up that summer, showed me some samples and I just liked it,” Wadsworth says. “It was bright, distinctive, a good colour scheme. And it looks well on photographs.” United wore it at Rochdale, when their latest Auto-Windscreens mission almost came apart at the last. After leading 4-1 from the first northern final leg, Dale scored two early goals.

“I was in the directors’ box and remember launching myself over the barrier, down through the crowd, and over the paddock to get into the dugout,” Wadsworth says. “Anyway, Derek scored before half-time and we were quite comfortable after that. It was a bit of a squeaker to start with.”

A 5-3 aggregate victory satisfied the Wembley yearning. “The club had never been there, so it was a massive day, walking out there, those colours, the deckchair army. Credit to Birmingham, they weren’t short of fans either. It was a fitting final – they won Division Two and we won Division Three. There was nowt in it, was there?”

Both sides had chances – Carlisle through Thomas and Paul Conway – before Paul Tait headed the winner for Barry Fry’s team in sudden-death extra time. “That was one of the strangest feelings I’ve had in my whole career,” Wadsworth says. “That golden goal, done, finished, kaput. We didn’t have the chance to get an equaliser. A really empty feeling. But, in the end, it didn’t detract from the day.”

United went on to clinch the title at Colchester and, a few weeks later, fans lined Carlisle’s streets as Wadsworth and his players embarked on an open-topped bus parade. The boss enjoyed this, as well as other, earthier aspects of the supporter-club relationship. “Your immediate interaction with the crowd is always that group behind the dugout,” he says, thinking of the Paddock. “Often they’re the older supporters, who’ve seen Carlisle a lot of years, and their approval or disapproval was quite marked. They would give you in no uncertain terms what they thought about certain situations. They were honest and as a manager you have to deal with that.

“When it came to the civic reception, we couldn’t believe how many people turned out. We’d lost our last game [to Lincoln] – probably influenced by alcohol intake that week – and were going to Spain on the Monday. The Sunday, how long it took us to get around the city…it was just amazing. For winning Division Three, flipping heck. Amazing that so many people could be bothered to come out.”

It was those scenes, and that overflowing of sentiment, that, the Yorkshireman says, “enveloped” him forever into Carlisle. “By osmosis almost, in a situation like that you become part of the city. I’ve still got dear friends in Carlisle and I come up a lot. I would say it’s the place I hold most affection for in all the places I’ve worked. It just engendered a sense of belonging.”

It still frustrates Wadsworth how things subsequently unfolded: a summer of minimal signings amid the building of the new East Stand, a relegation battle in the third tier and certain events he is reluctant to detail which led to his mid-season decision to leave for the No2 post at Norwich. This was accompanied by a press conference in which a number of parties were in tears.

“Perhaps I could have handled it better, perhaps Michael could,” Wadsworth says. “I don’t want to criticise anybody and I’ll never say a bad word about Michael. Hand on heart I probably should have stuck it out. But I did what I thought was the right thing. It’s by the by. It’s life.”

Norwich was not a success. “I’d only been there a few weeks and thought, ‘I’ve made a right mistake here’. They were in financial trouble and, now and again, I’d find those letters from the Carlisle people and think, ‘Why the hell did I do that?’ I suppose when you make any decision, you try to make the right one. I just made a cow’s backside of that one…”

Wadsworth returned to management with a series of clubs, while his bond with Sir Bobby Robson led him to the great man’s side at Newcastle. Another surreal post saw Wadsworth take charge of the Democratic Republic of Congo for eight weeks; this spell – “the most bizarre, ridiculous, threatening, frightening, funny experience of my football life” – was, he says, riven by corruption and lurid events which he plans to cover in the autobiography on which he is working.

His most recent job, an academy position at Sheffield United, ended last year and Wadsworth, who turns 70 in November, says he is now content to “wind down a little bit”. He retains connections with clubs such as Sunderland and Manchester United, and does consultancy work. “I like helping young coaches the most. I’m the old fart in the corner now.”

On the balcony of the civic centre in 1995, the younger, moustachioed Wadsworth took a microphone and, addressing the huge swell of Cumbrians below, laughed about his image as a “miserable sod”. Yet there is great lightness in his memories of a twinkling United time – and, after all, it is not every manager who is capable of leading supporters to verse.

One fan who wrote to him penned a 14-line poem, and looking at it afresh transports you back to those fine, fleeting “deckchair” days which, as long as the Blues are in the fourth tier at least, they and their supporting community will always be trying to recapture. “For making us champions, when once we were lost / For providing a future, when all we had was the past / For creating ambition, for realising our goal / I thank you, Mick Wadsworth, from the depths of my soul.”

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here