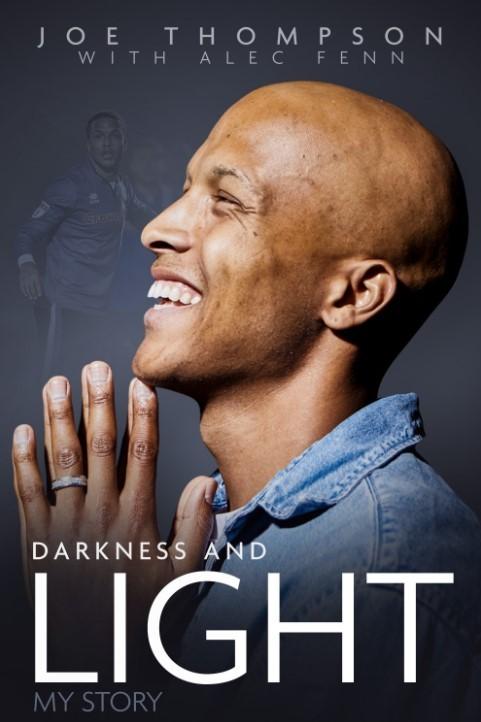

Our final exclusive extract from 'Darkness and Light', the autobiography of former Carlisle United player Joe Thompson.

The room was a blank canvas, filled with the stench of bleach. All I had for company was a television, an en suite and a window, which offered me the only glimpse of the outside world I would have for up to two months.

I’d overcome battles at home, in the playground and on the football pitch, but this was life or death, and my opponent was hell-bent on getting revenge.

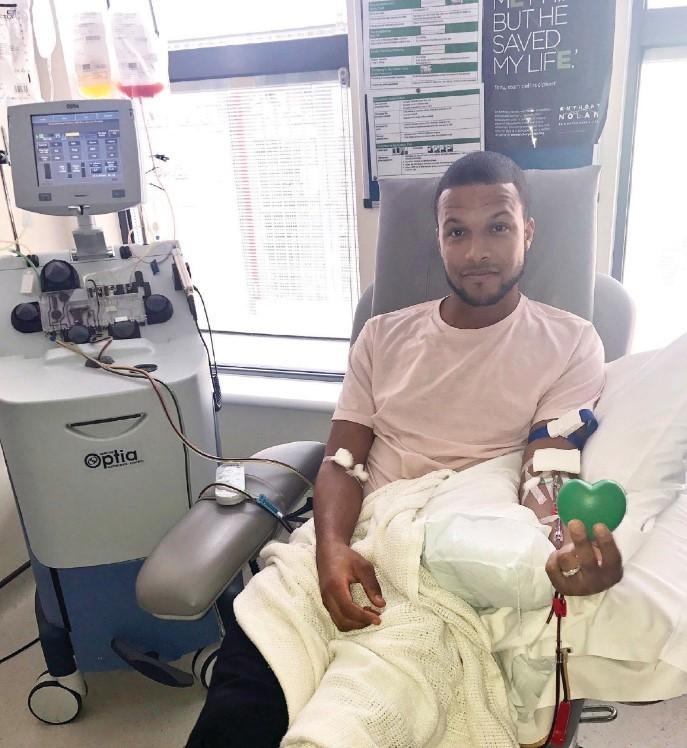

It was June 3, 2017, and I was sat on my bed in one of the dozens of isolation rooms at Christie Hospital, preparing for my final week of chemo, before undergoing a stem cell transplant.

The chemo was that powerful, it had attacked cancerous cells, but also killed white and red blood cells and platelets I needed to fight infections, transport oxygen around my body and basically stay alive.

This meant I had to be locked away for an indefinite period of time until my immune system was strong enough to survive in the outside world without medical assistance.

Players are often perceived as alpha males, trained to bottle up their fears as a way of surviving in a ruthless sport. That might be true for some, but I’ve never seen myself as a macho man, and would openly admit I was scared.

When my doctor came in to explain the process, I asked him not to tell me which symptoms I was likely to experience and make sure the nurses did the same.

It was my way of waging mental warfare against cancer. If I knew exactly what was coming, then perhaps my mind would begin playing tricks on me and I’d imagine pain that wasn’t really there.

Instead, I wanted to know the record time a patient had recovered from a stem cell transplant and made it out of isolation. His answer was 21 days. Footballers relish having targets to hit and in my head I vowed to break that barrier. To pass the time, I’d spend hours scrolling through my phone looking at old pictures and videos and seeing what my friends were up to. I saw team-mates on holiday in Las Vegas with smiles on their faces. I’d been there 12 months ago for my stag do and had the time of my life with my closest friends.

I wondered if I’d had my last holiday, but I tried to combat those negative thoughts by reminding myself of the rich life I’d lived up until that point. I’d played football for a living, married the girl of my dreams and recreated life. If this was the end of the road, I was content with everything I’d achieved at 28.

My concentration started to waver and I became increasingly sensitive to light, which meant watching DVDs and reading books was almost impossible. I was struggling to keep food and liquid down and my weight began to plummet.

More worryingly, I noticed a change in my doctor’s and nurses’ tone of voice. They sounded panicked as their visits became more frequent. I needed blood transfusions to try and boost my white and red blood cell count.

On day ten, hallucinations haunted me. During one bizarre episode, I was convinced a SWAT team had abseiled down the outside wall of my room, smashed my windows in and were about to perform open-heart surgery while I was strapped to the bed fully conscious. I woke up shivering and sweating like Gollum in the corner of the room with a nurse looking over me.

Emotionally, the following three days were the worst of my life. I spent 36 hours in and out of sleep. Every time I woke up my bed looked as if a dog had shed its fur over the sheets and pillows.

I desperately missed my daughter. It was the longest period we’d been apart since she had been born and I worried what impact my suffering would have on her in the future.

After three days of horrendous suffering, my white blood cell count at last began to shoot up, which meant the stem cell transplant was working. My first wedding anniversary was approaching and I was deemed well enough for Chantelle to pay me a brief visit to celebrate. Before she arrived, I watched our wedding video back on my iPad. It brought a tear to my eye. My wife had remained by my side in sickness and health – that’s true love.

Children are normally banned from visiting under any circumstances, but with Father’s Day just around the corner, I decided to defy doctor’s orders and asked Chantelle to bring Lula in.

I hadn’t washed in two days, because the change in temperature when I stepped into the shower cubicle caused me to be sick, but I made a special effort for my little girl because I didn’t want her to be alarmed when she saw me.

She was only with me for about 40 minutes and spent most of it playing games on my iPad, but it was worth it just to receive a card she’d made for me and to see her smile after I gave her a hug.

I felt like I’d been plugged into the mains and given a boost of power. My spirits had been raised and I could feel my competitive streak returning.

On day 16, my friend Nicky Adams and Rochdale team-mate Brian Barry-Murphy joined Chantelle by my bedside. Shortly after they arrived, Dr Gibbs came in with some news. “You’ll be glad to hear your immune system is strong enough for you to go home, Joe.”

My reaction should have been one of elation, but instead it was mixed with fear. I held on tightly to the metal rails on the side of my bed and argued that it was too soon. I realised I’d almost become institutionalised. I looked at Nicky and asked him not to tell anyone about my reaction. I was embarrassed and didn’t want people to think I’d gone soft.

In the end it didn’t take me long to pull myself together. I told Chantelle to pick Lula up from school and bring her into the hospital for 1pm the following day.

The three of us would leave together as a family. As I left the room for the first time in 18 days, I realised I’d smashed my target and set a new record for an isolation patient at Christie Hospital.

The sun was still shining brightly when we got home, so I pulled up a chair in the back garden and basked in the feeling of the rays hitting my skin.

I was out of the woods. The chemotherapy and stem cell transplant had been a success and somehow I’d beaten cancer for a second time.

*Darkness and Light, by Joe Thompson with Alec Fenn, is published by Pitch Publishing, £18.99.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here