As the game drifted into its final seconds, the Hull City winger, Arthur Cunliffe, surged through on goal. Carlisle’s goalkeeper Thomas Knox was ready, and denied him with a superb save.

It was an impressive last gesture of defiance from the Blues, even though a goal would not have counted, given the final whistle had already blown. It was also, sadly, a token act in another sense, given there had been 11 previous occasions when things went rather better for Hull.

For Carlisle, less so. If eyebrows were raised when Manchester City put nine past Burton on Wednesday, at least the Brewers avoided the indignity of double figures. United were not spared such a fate in their Division Three North game on Humberside, 80 years ago tomorrow.

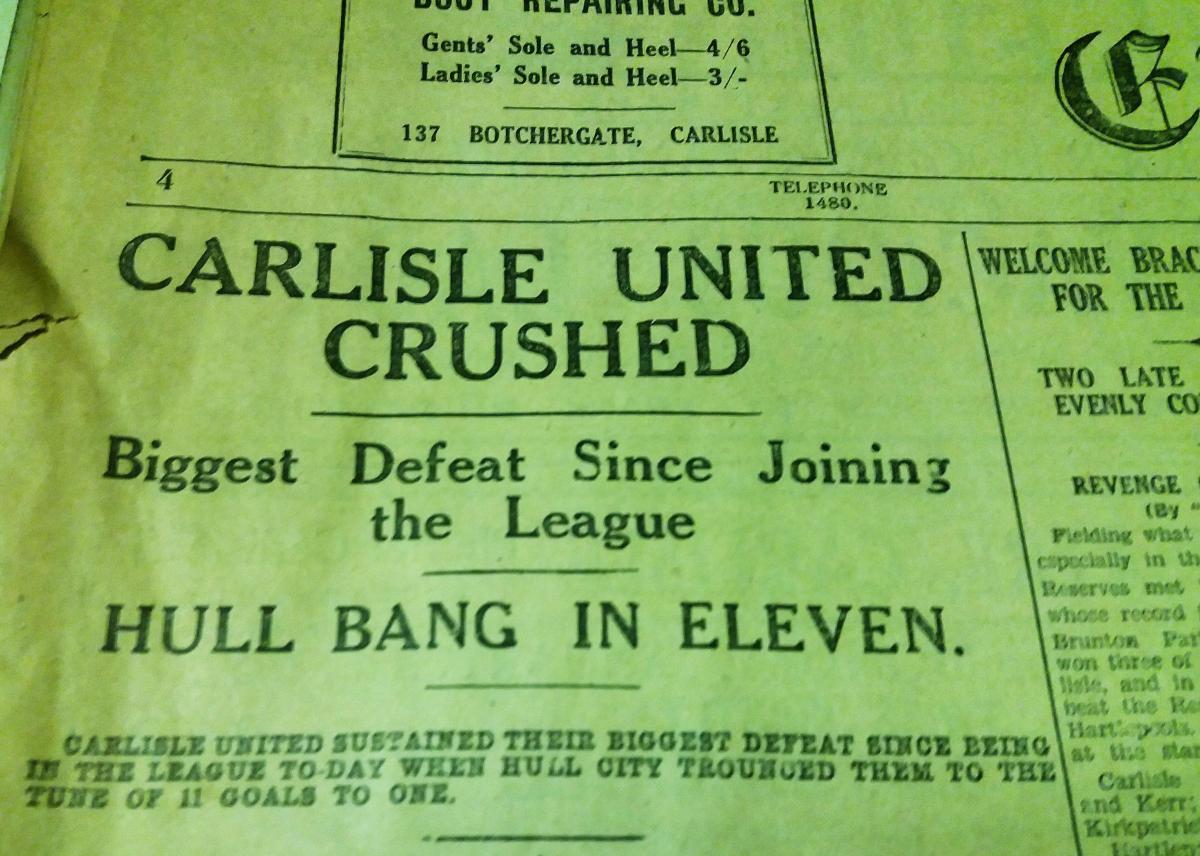

Their 11-1 thrashing remains their biggest league defeat, a notorious counterpoint to a present time when more positive records have been chased. It came at a time of change and, in one respect, deep controversy, also arriving in the final full Football League campaign before World War Two.

Hitler’s “sabre-rattling” was gathering headlines in January 1939 but life, and football, was still proceeding normally. Long gone, as Carlisle started their 10th campaign as a Football League club, was their initial talisman goalscorer Jimmy McConnell, yet while summer 1938 had seen 14 players depart, the eight who came in were described as a “hefty lot”.

Under Scottish manager David Taylor, they opened with a 2-0 win against Hartlepools, yet mediocre results left them in lower mid-table come winter. This then paled into the background as the Blues were named in one of the biggest scandals to strike the game.

January 3 saw a joint commission of the Football Association and Football League report its findings into alleged illegal payments to players. A former Stockport director was suspended and 11 Carlisle players, current and former, were fined.

The controversy concerned claims that money had been given to various players after a game against Lincoln in April 1937: a Blues victory which helped Stockport’s promotion cause. Some of those at United felt their punishment, paid in £1 weekly instalments, was severe. “We will have to get this back in bonuses,” one told The Cumberland News. “The opposition teams we meet from now til the end of the season will suffer this.”

Abrasive words, yet events did not quite correspond. United’s last game of 1938 had been a drab 1-1 draw with Darlington which brought “considerable barracking” from supporters, then two weeks later came their trip to Anlaby Road, Hull.

The home side were in the top half, compared with United’s 15th, yet there was no real warning of what was coming. Hull had conceded six in their previous two games and their biggest win to date was 4-0, against Barrow. Their previous Carlisle meeting, at Brunton Park in September, had brought a tight 2-1 away win.

On a chilly January 14, a 5,200 crowd rose for “Abide With Me”, honouring a late Football League president. The game then began on a heavy, sanded pitch with United setting a deceptive pace.

Taylor’s men competed aggressively, centre-forward Sam Hunt a threat and outside-right George Embleton denied a goal by offside. Even when Hull took a seventh-minute lead through Billy Dickinson’s flick, United were in the game. James Murphy struck the crossbar and a Hunt attempt was cleared off the line. “This was another fortunate escape for the Tigers,” wrote 'The Traveller' in the Cumberland Evening News.

Fortune, sadly, then fled completely. Hull’s attacking found greater flow and midway through the half they scored twice more, George Richardson converting a cross and Cunliffe cutting in to shoot past Knox.

A 3-0 deficit was not Carlisle’s only concern, since two players had to be treated for concussion after heading the heavy ball. More scrappy exchanges followed before Charles Robinson converted Hull’s fourth.

Before the break then came perhaps the smallest footnote in any United defeat: their consolation goal, dispatched by Hunt almost straight from the restart. In the first eight minutes of the second half, they then shipped three more, through Cliff Hubbard, Richardson and Cunliffe.

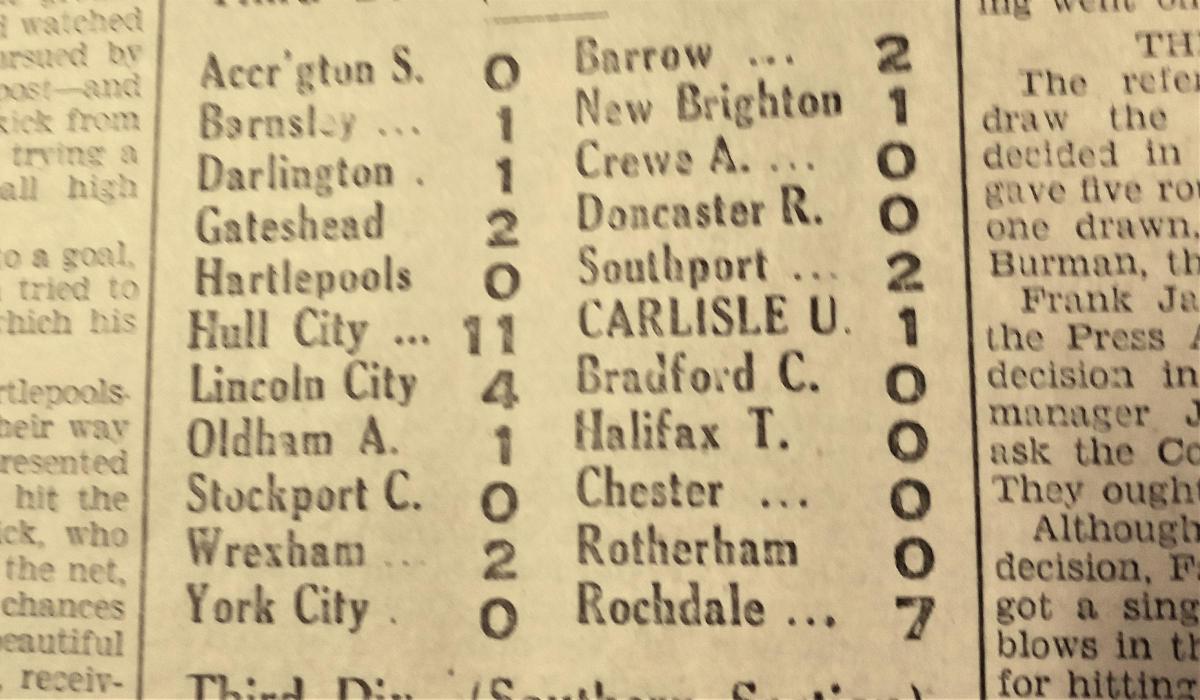

There was no accounting for their defensive weaknesses - and Hull were ravenous. With 20 minutes left, Hubbard drove in the eighth and Dai Davies struck a ninth, before double figures were reached in the 86th minute through Dickinson. With two minutes left, Davies headed home number 11.

In an obvious sense it had been a great humiliation - yet Carlisle’s response was restrained. “They took their beating like a sensible set of players should,” The Traveller wrote, describing how rival players left the pitch shaking hands. A Hull director added: “You have the most sporting and game team I have ever seen.”

Later reflections focused on Hull’s roving attack and United’s weakness at half-back. Yet, in a report whose tone would find favour with some of today’s more sensitive football directors, Carlisle’s correspondent also wrote of the “clean and plucky game” they had played.

It is tricky to swallow, in light of the scoreline, the assertion that “had they scored in a good first 15 minutes, the game would almost certainly have taken a different turn”, not least because their next fixture proved only slightly kinder: a 7-1 defeat to Crewe, described by another writer as “not so bad as it looked”.

What a seriously bad day would look like was not fully set out. Mercifully, it did not go as poorly again, though the Blues still ended the campaign 19th out of 22, their equal second worst finish in their first decade as a League club. Hull came a more creditable seventh a few months before football, and normal life, was suspended - while in all the years since neither has got particularly close to the records set that January afternoon.

It remains the Tigers’ biggest win, as well as a landmark loss which Carlisle will be happy to see recede a little further into a long and distant past.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here