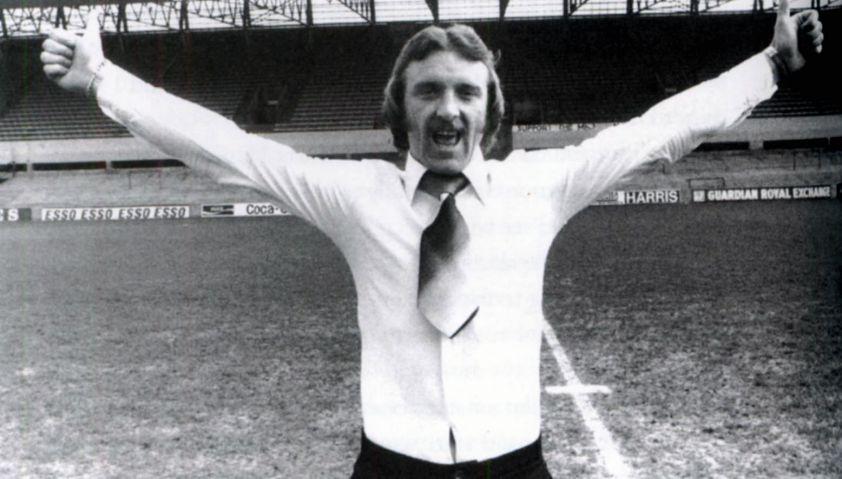

Back in 2007, when Kevin Beattie was launching his autobiography in his adopted town of Ipswich, arguably the greatest of all Cumbrian footballers was taken aback by the response.

"What surprised me," he said, "was how many kids were there. They never saw me play, but they said they were keeping the book for themselves, not for their dads or uncles."

They had, one imagines, been told. And if you hadn't been fortunate enough to see Beattie, but were brought up to speed by someone who had, what you heard was extraordinary.

It was, above all, a career not defined by numbers, or even necessarily medals, but by a higher tribute: how people felt when Beattie played. What they remembered. What they said.

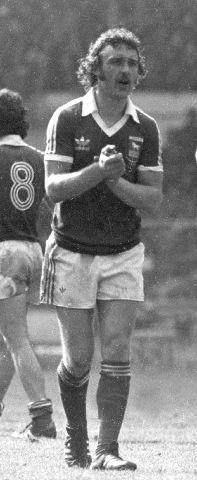

And so, as those memories surge back in the week of his death at 64, it is far better to sidestep the statistics, since his nine England caps was an absurdly small number for a player of Beattie's gifts. Even his 307 Ipswich Town appearances might have been doubled were it not for the injuries that led to retirement at 28.

It is much better to think, instead, of what the giants said about this Botcherby lad. Sir Bobby Robson, no less, felt that, after George Best, these islands had produced no better footballer in a 25-year period.

That in itself is a breathtaking claim. Not Charlton. Not Law. Not Edwards. Not Greaves. Not Moore. Not the scores of others who dazzled in Robson's long era.

No - to Robson, it was Beattie who was the total package, the footballer you would design if given a pick of all the qualities required. He had pace, he had strength, he had a leap so high "he could have seen the town hall clock and told you the time", as Robson put it in his own book. He had a left foot that produced piston power. He had timing and presence. He had heart, that part of the body that tragically failed him in Sunday's early hours.

He had, when you saw all these pieces assembled, nothing less than the highest class.

Another time-honoured compliment was that made by Bill Shankly, who reasoned that not signing Beattie was one of his few mistakes, perhaps his biggest.

Again, take a pause. Shankly: one of Britain's most iconic managers. Shankly: architect of Liverpool's golden age. Shankly: whose personality filled stadiums and transformed clubs. Shankly: greatness unsurpassed.

These sayings, Shankly's and Robson's, have been repeated so often they run the risk of losing impact, yet as Carlisle, Ipswich and football mourns Beattie now, they ought to be considered in fresh light. For they capture the true scale of the man this county and its city somehow produced and sent into the national game.

Beattie's book, written with Rob Finch, was of course absorbing. How could it be anything else? It was a life often lived the hard way, a journey studded with pitfalls and near tragedy, tough times forging the young man and accompanying him during and after his rarefied rise.

"There were times I didn’t go to school because I didn’t have any shoes," he once told me, reflecting on childhood. "I had four brothers and four sisters, and we were a poor family. There would be times I would have nothing to eat for two or three days, unless my dad won a game of dominoes at the pub and got the fish and chips in.

"But my teacher at St Cuthbert’s School, Mr Rafferty, bought me a pair of boots. They were my crown jewels. I looked after them like nothing else on earth. Even at that age, football was a release for me."

Beattie spoke unsparingly about home life; how his father, Tommy, drank; how Kevin later returned to Carlisle to "sort him out" in order to protect his mother; how, after mellower years, he lovingly buried Tommy in one of his England suits, and later his mum alongside, in a plot in Carlisle Cemetery which he had bought specially.

He also spoke innocently about his love of Carlisle United: his collection of cigarette cards, the rattle he made at school, days in the Warwick Road End, adoration of Hugh McIlmoyle, the Blues' princely centre-forward. His regret, later, that although he eventually coached his home-city club under Roddy Collins' management in 2002, he had never pulled on the shirt as a player.

The shame is that Carlisle, in the 1970s, were not adept at securing local talent. John Carruthers, the masterful scout from the city, was never asked to work for the Blues either and instead recommended Beattie first to Liverpool, where Geoff Twentyman was Shankly's trusted pair of eyes, and then - Beattie having travelled to Lime Street station, only to get the train home when nobody from Anfield had turned up to meet him - to East Anglia.

Beattie did not know where Ipswich was, but knew it was a professional football club - and also knew, after one trial game, that Robson wanted him badly. His debut was at Old Trafford, against Best, Charlton and Law. Ipswich won 2-1 and Beattie set up the winner.

From here his path seemed glitter-strewn. He was the inaugural PFA Young Player of the Year in 1974 and was picked for England's under-23s, despite the day when, shortly after his first child had been born, the young defender felt tired and homesick and went to see his parents instead of joining up for a training camp.

He was photographed in Botcherby's Magpie pub and savaged by the newspapers. Yet Beattie rolled on, given a full England debut against Cyprus aged 21, later scoring for his country against Scotland, tipped for "150 caps" by the devoted Robson.

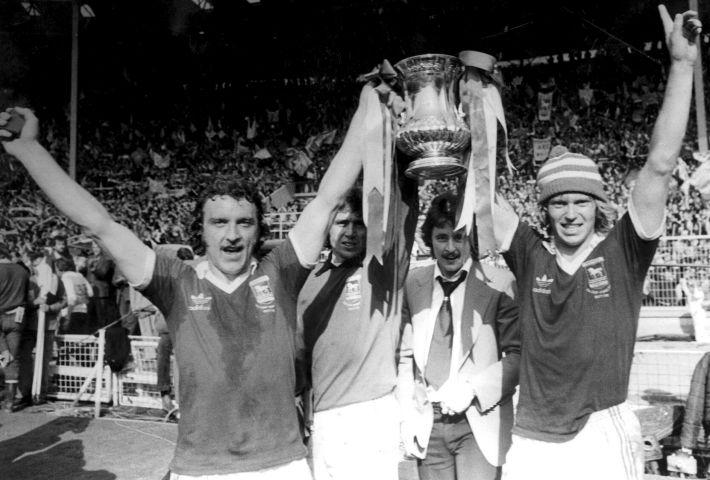

It was not, though, a story of the squeaky-clean or the comic book. One time, Beattie tried to burn some leaves in an oil drum in his garden, injuring himself so severely he missed the rest of Ipswich's season. In 1978, though, he helped the Suffolk club win the FA Cup, gasping on a cigarette after Roger Osborne's goal had defeated Arsenal. "I held that medal tight in my hand," he later said. "It was one of the greatest days of my life.”

Carruthers had sent other fine Carlislians to Portman Road - David Geddis, Robin Turner, Steve McCall - yet Beattie was the best. The travesty is what fate did to his body, a broken arm ruining his chances of a UEFA Cup winner's medal in 1981, and more persistently his knees, which started failing him in his twenties, were pumped with cortisone even at his magnificent peak, and led to premature retirement, a decade sooner than he had imagined.

He left the game as Ipswich's best-ever player yet walked into dark times. Entering the pub trade, he drank too much and suffered such damage to his pancreas that, one morning in hospital, he was given two hours to live and read the last rites. His residual strength and fitness, from those powerful football years, saved him then.

Weaker but wiser, Beattie suffered differently when, unable to work because of his knees, and signing for benefits opposite Portman Road, he was depressed and considered suicide.

A plan involving an array of pills and a bottle of vodka was intercepted by a friend. "Someone up there was looking down on me that day," he recalled. "He sent my friend round, out of the blue, and really, he saved my life."

Beattie reflected openly on these stark times when, as a grandfather and carer for his wife Maggie as she confronted multiple sclerosis, he became more contented, and proud - or "lucky", as he sometimes put it - to have got past life's worst challenges. Those who worked with him more recently in the Ipswich media have, since Sunday, remembered a kind, friendly, avuncular man, one who wore his greatness lightly, one whose eyes twinkled just gently when you asked about his brilliant days in England's sideburns and flares era, not to mention some unlikely tangents, such as Beattie's role in the film Escape to Victory , when he was Michael Caine's body double and, off set, beat Sylvester Stallone in an arm wrestle.

Again, they are tales that make you blink. Those who knew of Beattie from the outset, who always identified his force, might think it the most amusingly appropriate epitaph of all: this boy from Botcherby who had too much power for Rocky and Rambo combined.

Those who knew football best would settle instead for what he did on a pitch: more naturally than so many of his generation, a "diamond" as Bobby Robson also put it, a golden-locked hero who played like others wished - and, from this small but proud city, better than anyone who has ever put a boot to a ball.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here