If referees feel they get a bad rap today they should perhaps count themselves lucky not to be operating in an era when things were, well, just a little more abrupt.

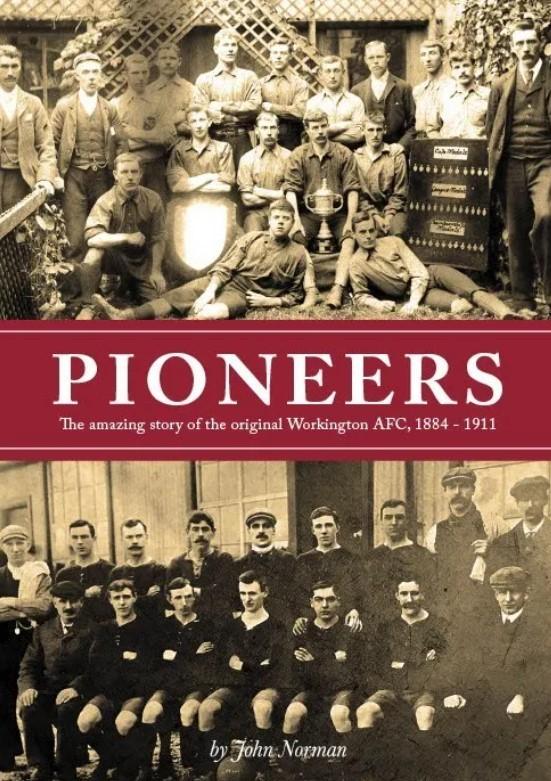

Consider the story from the 1908/09 season which is recounted by John Norman in his book ‘Pioneers’, which tells the history of the original Workington AFC.

The game concerned was staged on January 23 1909; a Lancashire Combination game between the Reds and Manchester United reserves, no less. The west Cumbrians lost 3-0 and decisions made by the ref, a Mr Bell from Oldham, were decided by spectators to have unfairly favoured the big-club visitors.

A section of the aggrieved home crowd were so incensed that they burst onto the Ashfield ground and surrounded poor Mr Bell, leading players, officials and police to step in and escort the official to the dressing room.

Yet that was not the end of the contretemps given what followed. The ref later alleged that, in order to evade another angry mob outside, he had been “forced to jump on a passing milk float” in order to escape to the train station.

Further allegations of visiting players being kicked and “hit with cinders” were later levelled, and this single game alone paints a picture of a feisty football era in which Workington AFC – the club that existed before the modern Reds – played.

There are many more anecdotes of a different sporting time in Norman’s fascinating book, which runs far deeper than tales about milk floats and fighting. It is in fact a fascinating, thorough and impressively detailed attempt to fill an often forgotten gap in the history of association football in Cumbria.

The Workington Reds that spent decades in the Football League and now functions in the Northern Premier League West Division at Borough Park only began in 1921. This was a full 10 years after the folding of the original Workington AFC: a club established in 1884 and whose history is, if chequered, short-lived and ultimately doomed, essential to understanding how the club game took root and flourished in the west Cumbrian town.

Norman’s book is not just football yarn but social history in the way it describes how an influx of steelworkers from the North Derbyshire and Sheffield areas, including the pioneering sportsman Fred Hayes, enabled football to gain a foothold in what had previously been a rugby league haven.

Norman is from Leicester but says he fell in love with Cumbria during a month spent at Eskdale Mountain School when he was 17. He took an interest in Workington during his time in the area and has devotedly followed the club since the 1970s, travelling thousands of miles to watch them in their latter Football League days and all their non-league adventures at various levels since.

“Apart from sport, my other interest has always been history, and although you could find snippets about the fact there was a Workington AFC before World War One, and that they went bankrupt, there were no real details about it – how did it start, who were they, who did they play against and so on,” Norman says.

“I’d retired after 50 years in the police force and suddenly we were in lockdown. I started looking online, one thing led to another, and I just went deeper and deeper into it.”

Norman’s original project was to produce something for Reds’ club website but his research grew so vast that a book became a realistic venture.

The finished product is clearly a story well worth the telling. It describes how Workington AFC grew from a new team playing on a field on Schoose Close into the biggest club in Cumberland. They had their hands on the county cup only three years after forming and also entered the FA Cup as early as 1887 (albeit losing 6-0 to Bootle in their first venture into the great knockout competition).

In piecing together these long-ago fragments, Norman also discovered a family connection which straddles the old Workington and the new – Alex McLuckie, full-back in 1887, was the great, great grandfather of Phil McLuckie, who played for Reds in recent years.

The progress of the first club was bold, ambitious and often embroiled in what must be described as typical controversies of the age, when no match, it seemed, managed to avoid being the subject of an “appeal” from the opposition. The slope on Workington’s pitch, the size of it, the manner of goals scored and pretty much everything else left many a game’s outcome the subject of interminable committee meetings and, in a number of cases, replays.

The developing game could also be rough. Goalkeepers were legitimately at the mercy of being barged over the line, while newspaper reports of an 1895/6 game against Black Diamonds castigated both sides for being “more interested in kicking a man than propelling the sphere.” One player was banned for a month for using “unsavoury language” - one can only guess at the Anglo-Saxon employed in such late 19th-century contest - while fighting even broke out at a benefit game for John Fisher, the young player who had tragically died after being struck by stones thrown by rioting Carlisle supporters following a county cup final.

Workington’s growth from local level to regional prominence brought other memorable episodes alongside the team’s rise and fall. The ample figure of William ‘Fatty’ Foulke appeared for Sheffield United in a friendly at Ashfield, the 20-stone goalkeeper so imposing that “no Reds player was brave enough to challenge him”. A Reds keeper, years later, was seen wearing an overcoat to keep warm while his team dominated one particular match, while in 1910 they tussled with Manchester City in the FA Cup first round, going down valiantly 2-1 to the future Second Division champions at Reds’ later home of Lonsdale Park.

If this, and other trophies won along the way, was evidence of a club with big aims, the eventual reality proved more troublesome. Workington AFC’s road to ruin, Norman writes, began when they thoroughly overstretched themselves, entering the North East League but also retaining sides in the Lancashire Combination and Cumberland County League. It extended the newly-professional club beyond their means, seeding financial problems which ultimately proved too much.

“One of the biggest problems was that, in the Lancashire Combination, the Lancashire clubs didn’t really want them there,” Norman says. “Travelling to Workington, as opposed to just around various conurbations in Lancashire, didn’t appeal to them and they put no end of obstacles in their way.

“As part of their being in the league, Workington had to guarantee travelling expenses. Then they decided to join the North East league as well, and had to pay travelling expenses there too. There was a sense of directors’ egos being devoted to the idea of being the biggest club in the area, and they thought spectators would flock to watch football every Saturday. But, really, they tried to con spectators – they were saying their reserve side, who played in the North East league, was the same standard as the Lancashire Combination. It clearly wasn’t, and crowds dropped off.

“The area was an industrial slump at the time too, early in the 20th century, and it just left the club up against it in all sorts of ways.”

Increasing entry prices, from 3p to 6p, was among other ambitious initiatives doomed to failure, with other attempts to avert the looming crisis unsuccessful. A share issue was poorly subscribed to, fundraising schemes (including the obligatory whist drives) raised limited funds, while an eventual withdrawal from the Lancashire competition came too late.

By 1910/11 the club was diminished. As the financial picture grew clearer, players accepted reduced wages, but then 10 key men left the club after being told they would not receive promised back pay. Local lads were summoned to replace Workington’s professionals and it was stark to think that, only a year after taking on Man City in the FA Cup, they were now losing to Lowca Juniors in the county cup.

The issues had become immovable. June 28, 1911 brought things finally to a head, when it was recognised Workington AFC were £1,600 in the red and directors recommended liquidation. The club duly folded, a 27-year story consigned to history and a 10-year hiatus following, before a new Workington AFC was formed.

It is the centenary year of that club now, yet Norman believes that the original Reds still have an important part in the overall story, and the restarting of Workington in 1921.

“There was that 10-year gap, the War in between, and I think people wanted something to take them out of the depression,” he says. “It must have felt like the right time to resurrect the club.

“The people who did that hadn’t been involved in the original club, but they certainly took notice of the mistakes that had been made in the past. The didn’t overstretch – they played in the North East league, and the reserves in local football – and, in fact, crowds proved better than what the original club had been getting.

“There weren’t huge connections between the running of the respective clubs, and the latter was certainly run on a far better basis. But the fact there had been an original club was still important. The new one got the ground (Lonsdale Park), they could call themselves Workington and they could play in the same red shirts. It was a case of improving on the original, rather than starting completely from scratch in every sense.”

The current club, Norman says, have been supportive in promoting his book, which can be bought (£12.99) via the Reds’ website, or directly from the author (johnnorman121@aol.com). It also supports an important and worthwhile cause; all profits from the publication are being donated to the Motor Neurone Disease Association in memory of the former Reds favourite Tony Hopper and a long-standing fan, Bob Atkinson, both of whom had the disease.

“Of all the players I’ve watched for Workington over the years, Tony Hopper was probably my favourite,” Norman says. “My daughter was mascot once against Blyth when Tony was captain, and he was so unbelievably kind and nice with her.

“Bob, who was known as Burnley Bob, was also a lifelong Workington supporter and somebody I stood next to on the terraces. All the profits from this are going to MNDA in their memory and I’ve been pleased already to send a cheque for a few hundred pounds to them.”

The memory of those men, and their original forefathers in red jerseys, is well served by this account of a fleeting but pioneering Cumbrian sporting time. “There’s been a lot of interest in it,” Norman says. “Maybe it’s something extra people will now talk about when they talk about Workington Reds. It’s a story that deserved to be told.”

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here