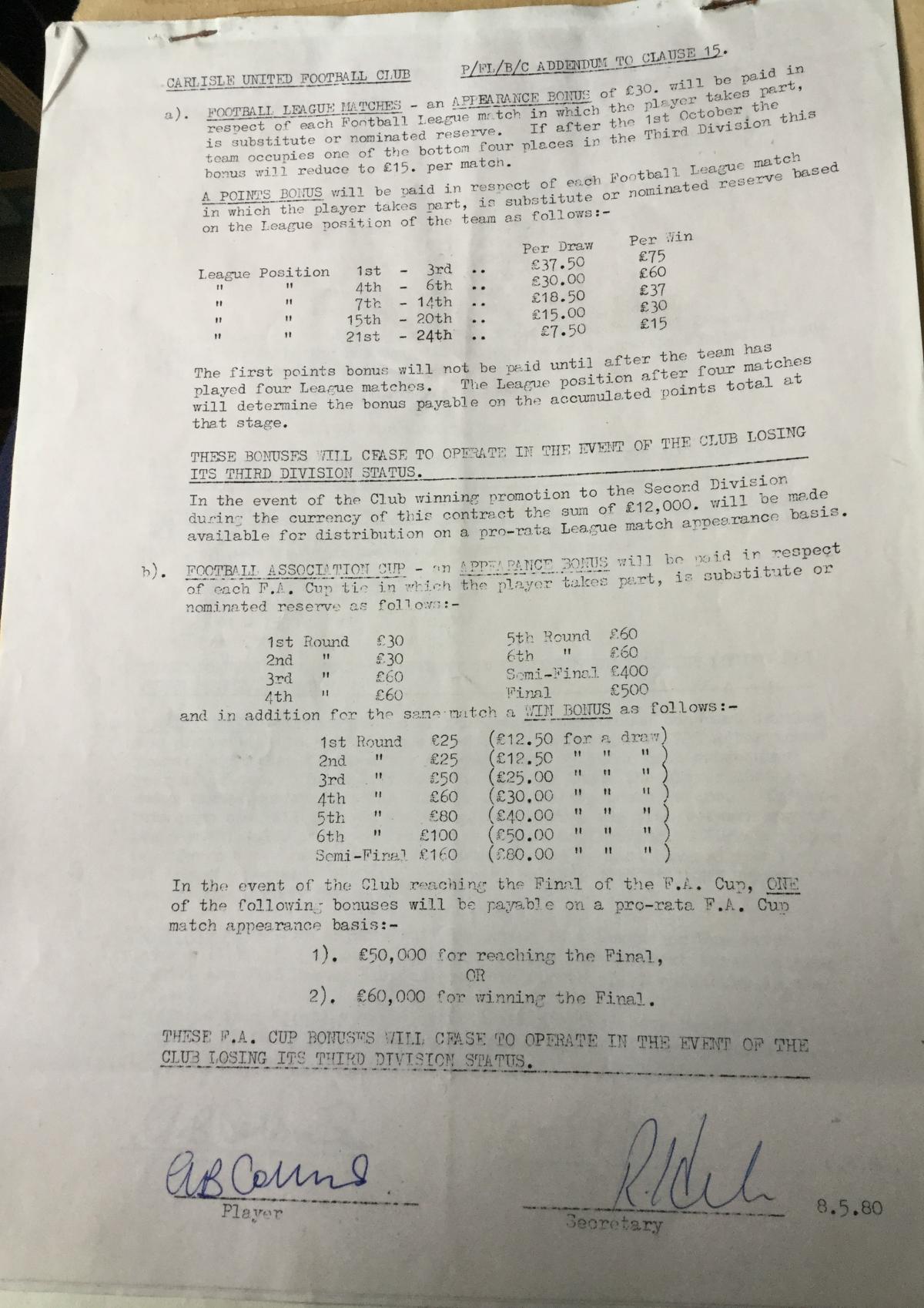

It begins with a basic wage of £120 a week, and the turning of the pages reveals more lucrative rewards available to Carlisle United players four decades ago. If a young professional happens to help the Blues’ reserves to a draw in the Lancashire League, for instance, he can expect an additional £1.50.

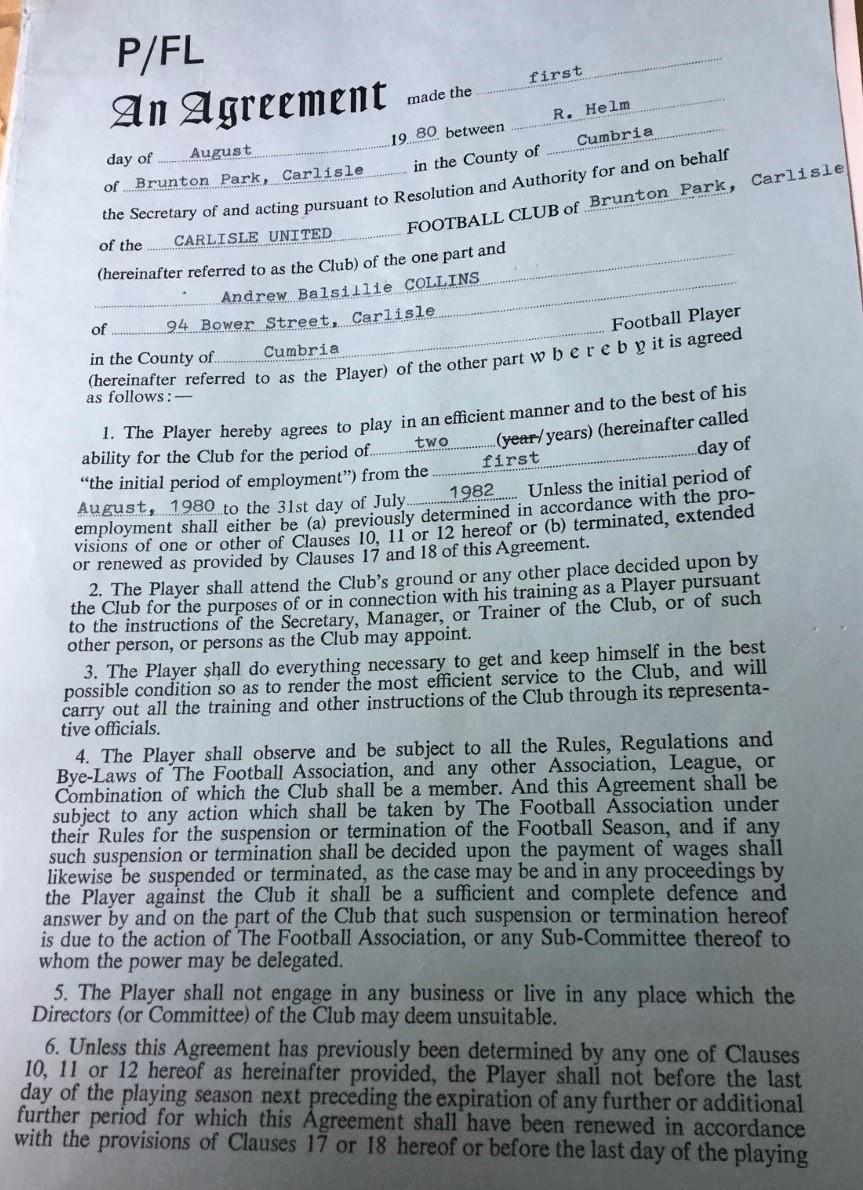

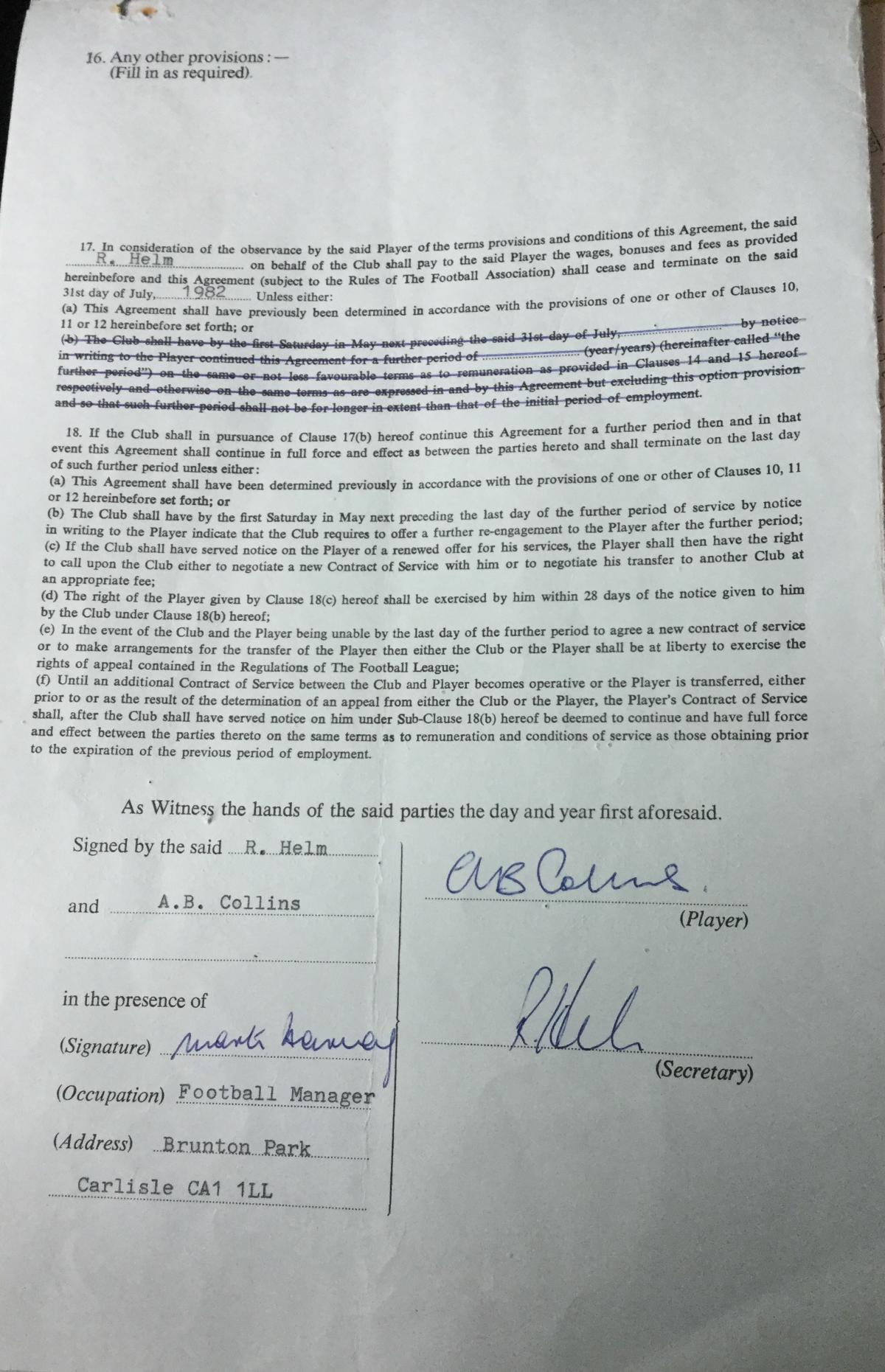

They are numbers from a different football age, and are preserved in a contract unearthed by the former Blues full-back Andy Collins. Some 40 years after signing it, Collins is now offering his old terms to United as a document of history.

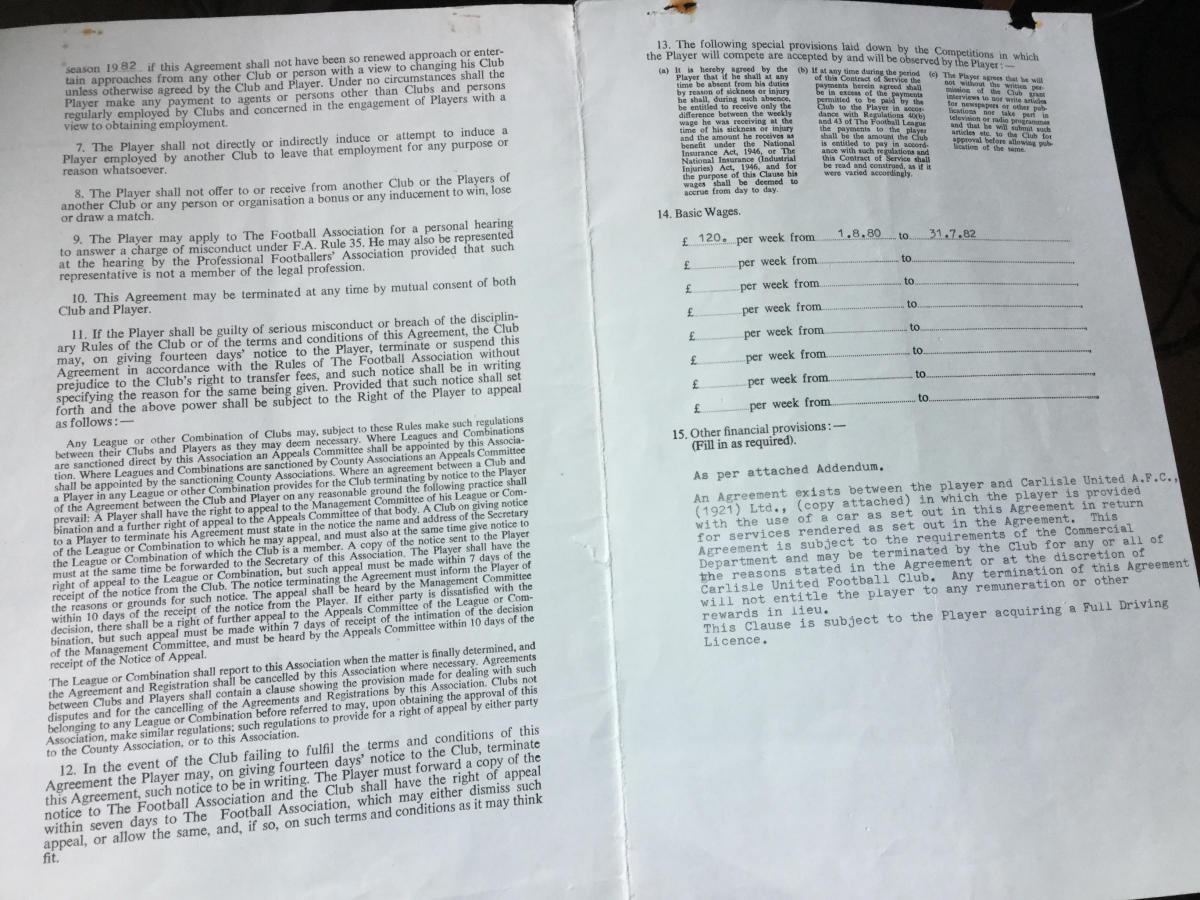

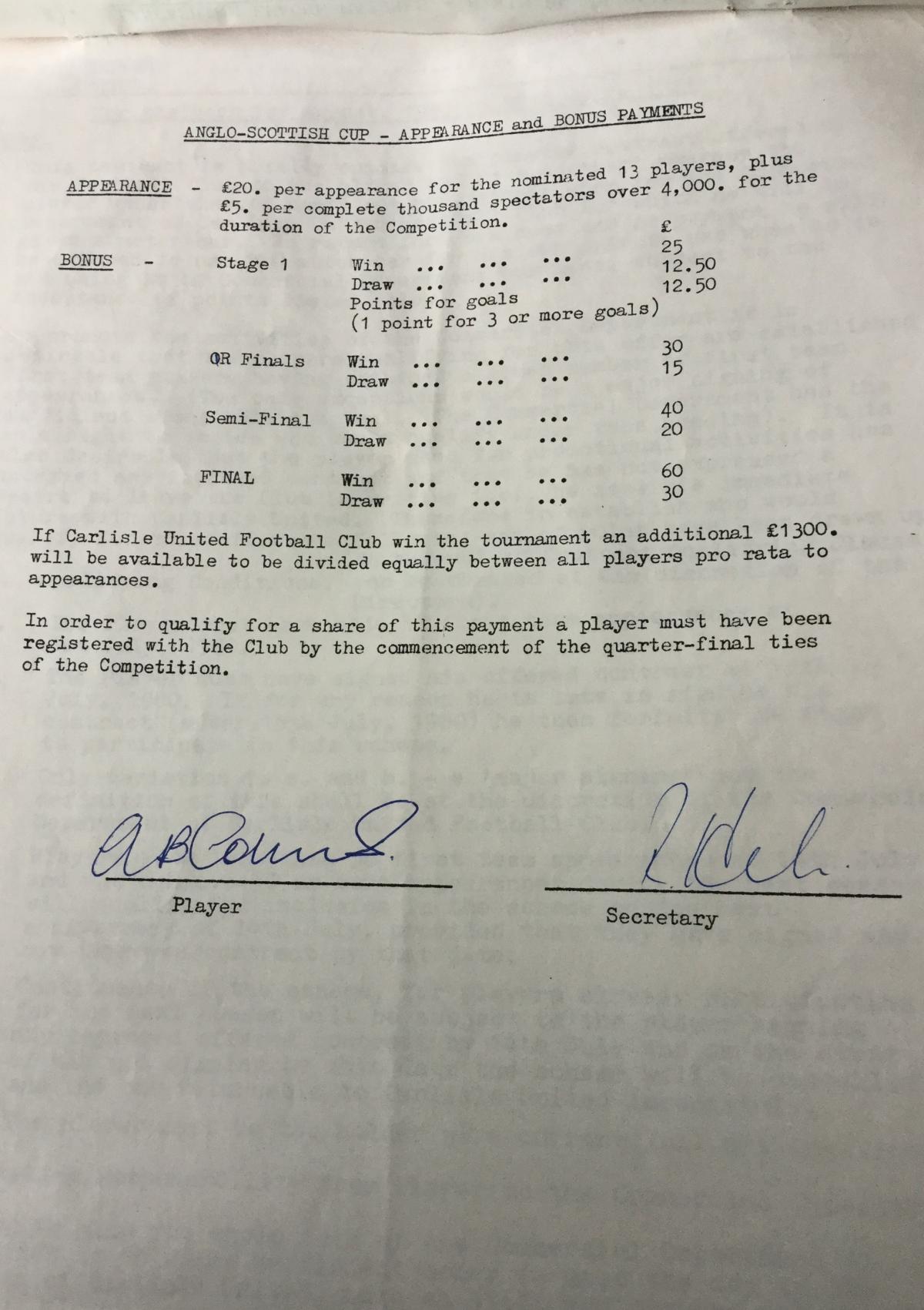

It records the fine print of life at Brunton Park in 1980. As well as wages and bonuses, there are stipulations on how a player had to behave, and what commercial obligations – and recompense – were also involved.

Collins, a Carlisle man whose second career as a journalist took him to Nottinghamshire, is whisked back to his young days as an aspiring footballer when he looks at the contract. The reminiscence was provoked when he returned to Carlisle last winter after his mother passed away at Eden Valley Hospice.

“The funeral was the day before Christmas Eve,” he says, and the next day we buried her ashes at Carlisle crem. While we were doing that, I went to lay some flowers where my dad’s ashes were buried. As we were coming back to the car, I bumped into George McVitie. He was there when I first started at Carlisle and was still there when I left. He wouldn’t have recognised me – I had shoulder-length hair and was 10-and-a-half stone wet through back then – so I had to remind him who I was.

“Meeting George certainly rekindled some memories, and about the same time I saw something in the News & Star about Carlisle United’s archive being basically destroyed [by floods]. Meeting George, and that story, made me wonder if I had a few things I could donate.”

Collins’ mum had given him a scrapbook some time ago and he recently brought it down from the loft to inspect the treasures within. His first contract with the Blues, signed in 1977, was there. Collins had also retained his third and final senior terms, by which point he had established himself as a first-team player.

“They first signed me on sort of a YTS apprenticeship contract,” he says. “For years Carlisle hadn’t had a reserve team, but when Bob Moncur was there, they decided to get it started. That’s the reason I went to the club – they had started looking around for local talent.

“Along with a few other lads, I went in to pre-season training and after a few friendlies they offered me professional terms. I’d just finished my A Levels and left school. I’d been offered a job as a trainee manager at Cumberland Building Society, tinkered with the idea of the Royal Marines, and had also been offered a position at a local Ford dealership.

“When Carlisle offered me terms, I thought, ‘I’ll give it a go for a year. If it doesn’t work out, so be it’. In the end, it did.”

Collins, who grew up in Bower Street, had come to United’s attention having captained Cumbria Schools, represented Carlisle schoolboys and even achieved an England trial. He had also played men’s football for Sunday pub teams and helped Carlisle Spartans to league titles.

He was given his debut by manager Moncur against Gillingham in 1977 and was a rarity in that era as a Carlisle-born player in the side. His initial wages were £37.50 a week, but appearance and win bonuses rendered his income more respectable.

“When I got in, and we had a decent run of results, I was probably on £120-150 a week,” he says. “I was getting paid four times what some lads were getting who I’d left school with.

“But I didn’t view it as work. You were doing what you loved doing and getting paid for it.”

Collins was thrust into a side that included players like Bobby Parker, Peter Carr, Billy Rafferty, Mick Tait, Phil Bonnyman and Ian MacDonald. “Ian strained his neck and missed a couple of games, so they moved Peter from right-back to centre-back. The idea was that I would fill in at right-back while Ian recovered.

“As it turned out, Peter and Bobby Parker established such a good partnership, they really tightened us up. And I must have done enough for them to think, ‘We’ll keep him in’.”

Collins played about 30 games in his first senior season. “I had a little hiccup in January with my hamstring and missed a couple of games. One was against Man United in the FA Cup. Because they’d printed the programme a week in advance, I was listed in the team, but didn’t play.

“I got back in, though, and played pretty much the whole season. It was a steep learning curve after schoolboy football. But I must have held my own.”

Collins progressed to an improved contract of around £80 basic. “As an 18-year-old lad in Carlisle – no mortgage, single – the money was good, or appeared to be. When you played other teams, you knew fine well their players were on considerably more. But it didn’t matter. Money was irrelevant, really.”

There was, he says, little in the way of negotiation when such contracts were tabled. “The truth is, I was green as grass when I went to Carlisle. A lot of other players had been apprentices somewhere, and had soaked up experience from older players, but I didn’t have any of that. When they offered me my first contract, they didn’t have to show me the terms. I just signed it. Even my second contract…I couldn’t believe I’d actually made it.

“During that off-season I went into the club and Bob Moncur said, ‘If you have another season like that, there’s a good chance you’ll play for England Under-21s’. That gave me a real lift.”

A fall, though, awaited Collins. A pre-season trip to Northern Ireland brought a cartilage injury and this heralded a knee problem which would recur in his subsequent two seasons. It restricted his appearance tally even though United retained the young player and improved his terms again with the 1980 contract.

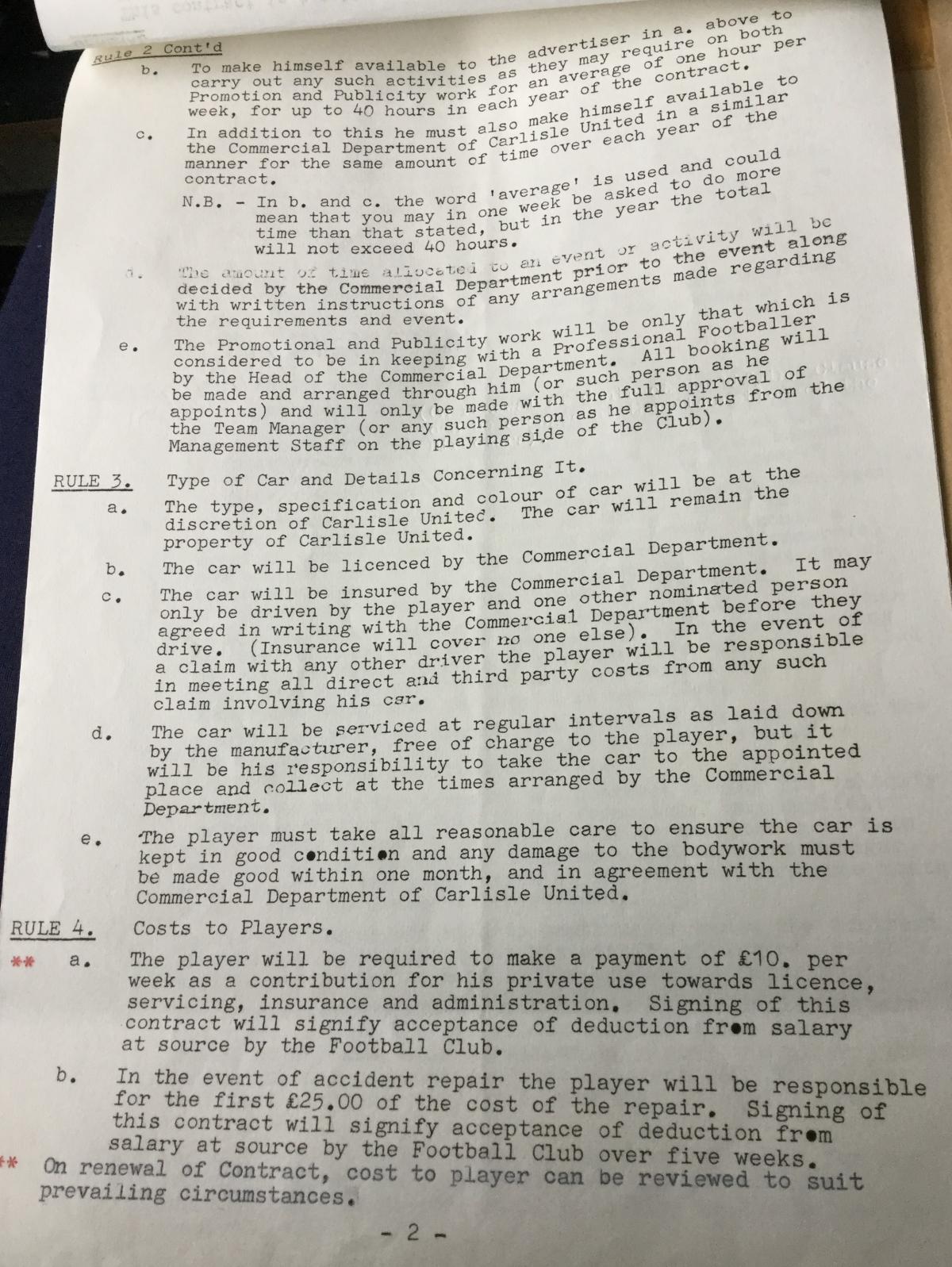

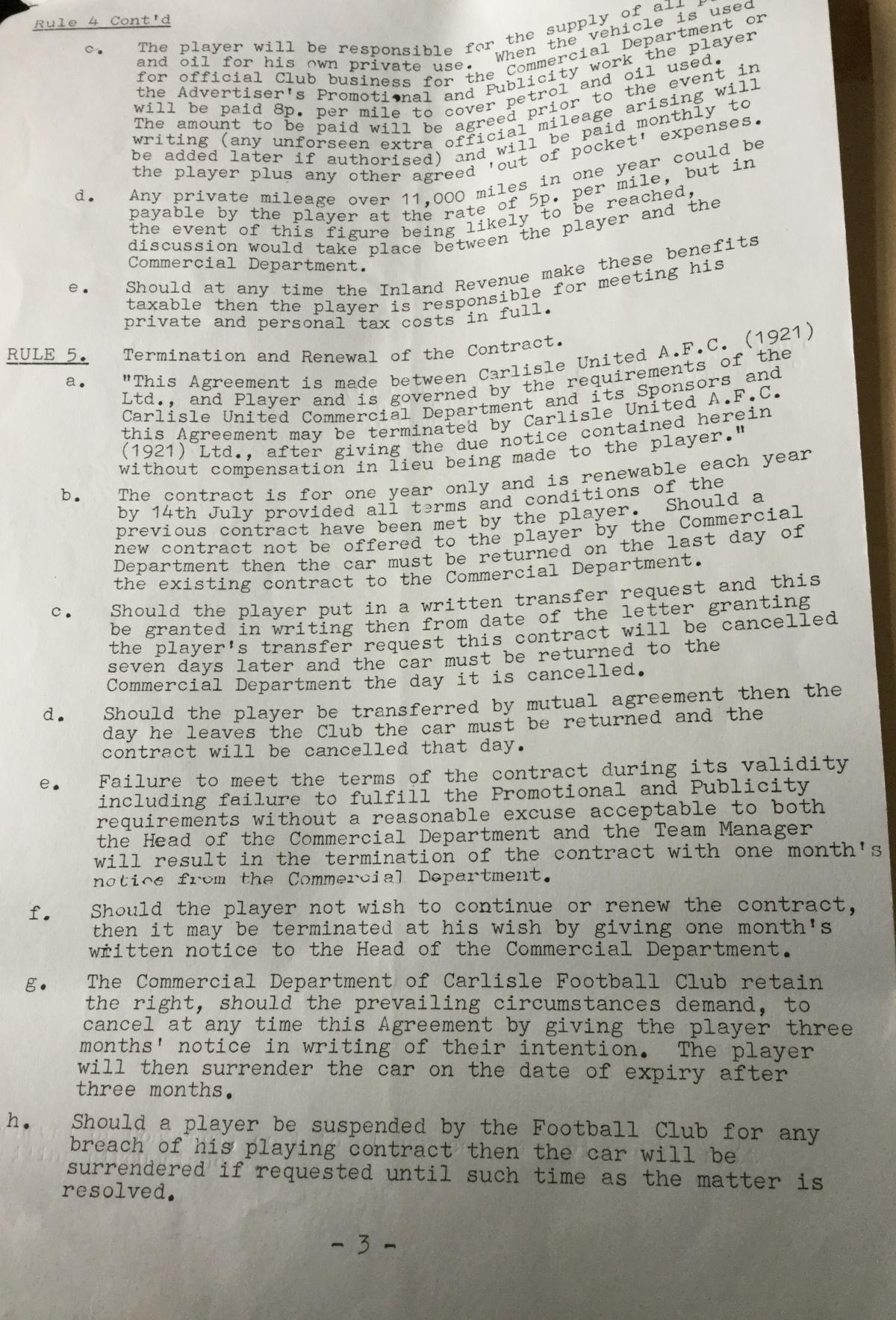

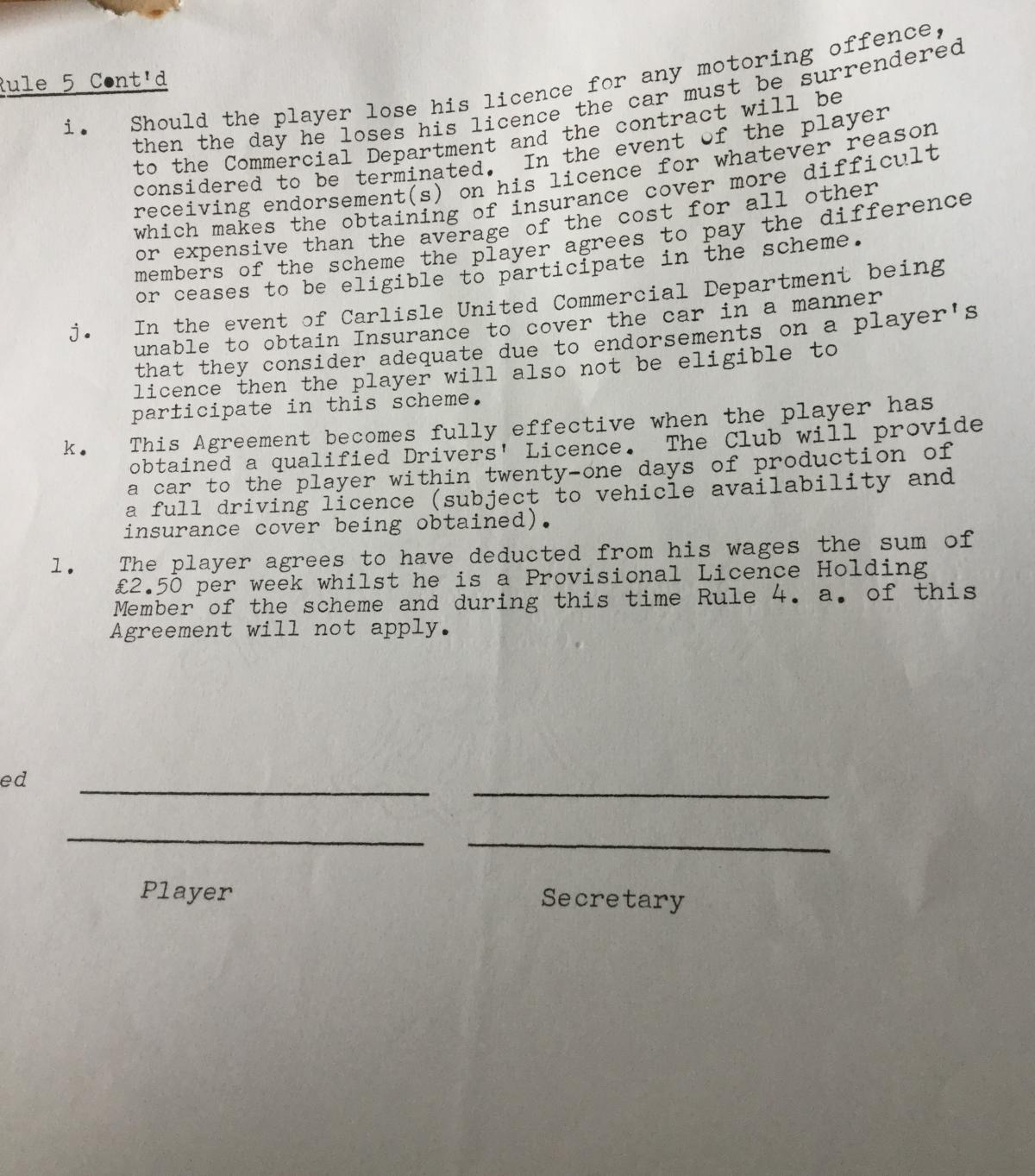

Its commercial terms raise a smile. The deal promised the use of a car, provided the player satisfied certain promotional obligations for the Blues. “It was a brand new Fiat four-door saloon,” Collins says. “One of the caveats was that you must have a full, clean licence. I didn’t drive at the time so it was an incentive for me to pass my test.

“I remember the day I passed it, bursting into a team meeting, shouting, ‘I’ve passed, I’m gonna get my Fiat now!’ The other caveat, though, was that the club retained the right to withhold the car if the club made a major signing. In the event we signed Paul Haigh from Hull, and, lo and behold, he got my bleeding Fiat…”

Collins enjoyed, though, the company of some of United’s distinctive players of the time. McVitie was a mentor and Parker was a sound pro. “Pete Carr was a complete headcase, but in a nice way,” he adds. “I remember my first season, we were playing Huddersfield away and we went for the pre-match meal in the George Hotel. I don’t know why – I didn’t question it – but all the players had a big steak, plus toast and tea, before the game.

“When the waiter came up taking orders and asked Peter how he’d like his steak, he said, ‘Pal, wipe its backside and take the horns off’.”

Collins got a close-up view of an even more thrilling player later in his United career. “When you played with Peter Beardsley for 10 minutes, you realised, ‘He isn’t going to be here long’. I remember his debut – horrible Tuesday night, blowing a gale, chucking it down, typical Carlisle weather. In the first 10 minutes someone lumped the ball away, aimless clearance, 40 feet in the air, and Peter killed it, nutmegged someone and then pinged it 25 yards to George McVitie.

“In training he also did things that were way above Third Division standard. I say all this, though, but the best natural footballer I ever played with – and that includes Beardsley – was a lad called Les Falloon. He played in the same Carlisle schoolboys’ team as me and he was head and shoulders above everybody on the pitch. I think he went to Liverpool but for whatever reason, didn’t become a professional footballer. I was gobsmacked when I heard that. If you’d asked me at 15 who’d play for England, I would have said Les Falloon without hesitation.”

Collins played under Moncur, Martin Harvey and Bob Stokoe as his five-year career with the club dwindled under the latter. He then followed a team-mate, Jim Hamilton, to South Africa for a spell, but had also been advised by a surgeon that he was unlikely to play professional football past 30. He had got to know the Cumbrian Newspapers sports writer Peter Hill on the bus to away games, and Hill gave Collins details of a journalism course.

This became his new route and a long career in newspapers followed as a reporter and sub-editor, predominantly with the Nottingham Post. This, as the decades passed, replaced football as Collins’ professional identity. “I was at Carlisle five years and in journalism for 30. When I meet people who ask what I did for a living, I say journalism.

“I never tell them I was a professional footballer. I did enjoy it, but when I walked into the pub, I knew people were looking at me, which I didn’t like. Football makes you appear a bit cocky and sure of yourself, but at the end of the day I was fairly shy, really. I enjoyed playing the game, not the goldfish-bowl lifestyle.

“When I came out of the game, I played a bit for Gretna in the Northern League – I was at college in Darlington and a lot of games were in the north east. When I got my first job on the Morecambe Visitor I played for Lancaster City, and when I moved to the Nottingham Post I played a bit. But the last time I played I was about 35 or 36. I’d got married and within a year had a son. Football didn’t consume or bother me. I knew I had to make a career somewhere else.”

Collins is now a grandfather at 61 and, in retirement in the village of Gotham, Notts, plays golf, enjoys the cricket at Trent Bridge and volunteers with Cancer Research. Harking back to the Blues has not been a regular pastime but his recent trawl for his old contract did reignite a few old thoughts.

“My one and only goal was against Brentford,” he says, “and to this day I remember Ivor Broadis coming up and saying, ‘What a cracking goal that was’.

“For most of my life, I’ve pushed it to one side. But things like that do come back.”

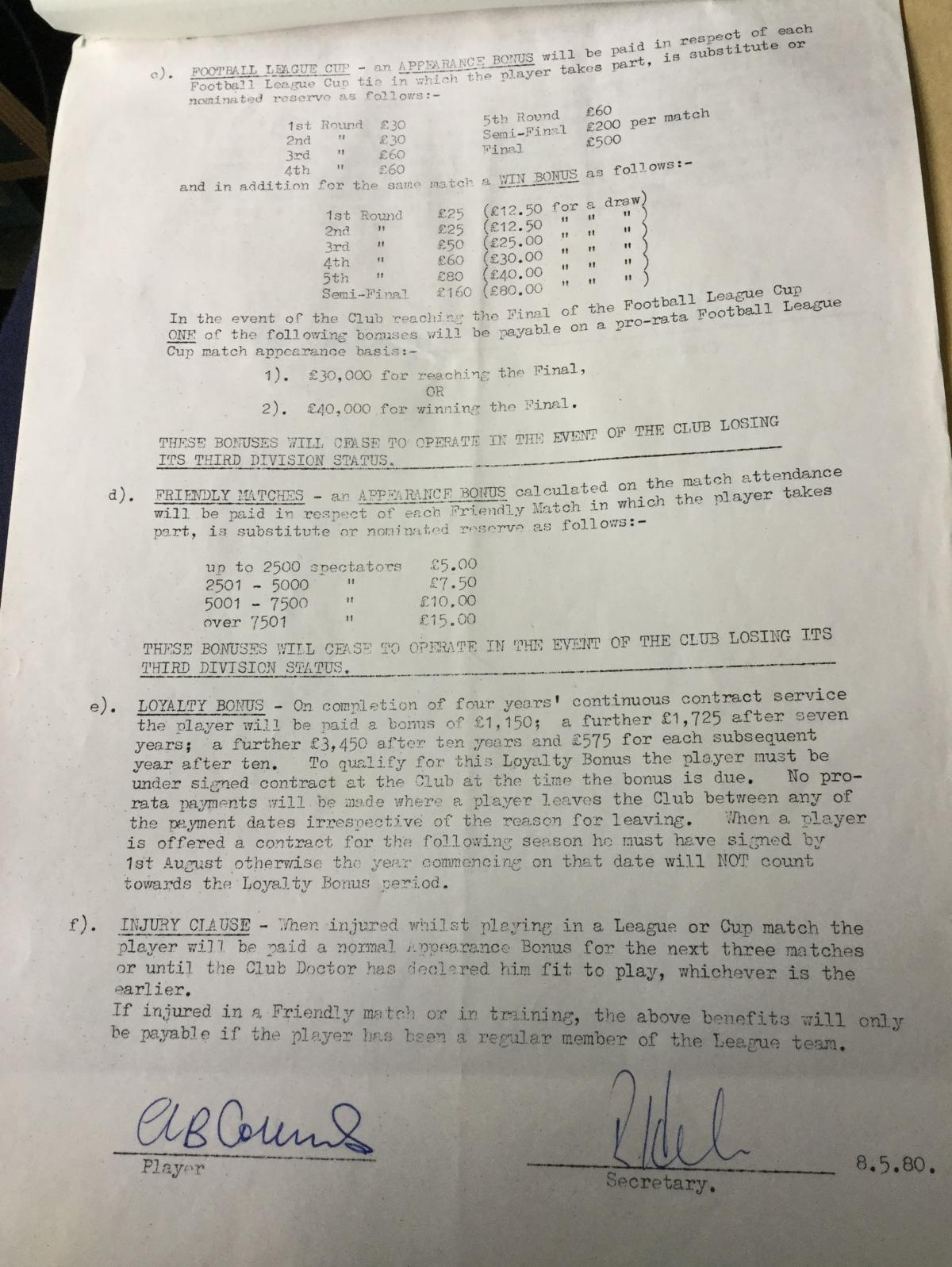

“There’s something else,” he laughs, thinking again of his contract. “There’s something in there about four years of continuous service guaranteeing you a payment of £1,150.

“I never received that money. When I signed the contract, I basically put it in a drawer without reading all those boring little clauses...

“I don’t know if the club ever checked it, but technically they owe me that money. My wife, Tracey, said, ‘Are you gonna chase them for it?’

“I said, ‘Tracey, it was 40 years…I’m probably prepared to let it go!”

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here