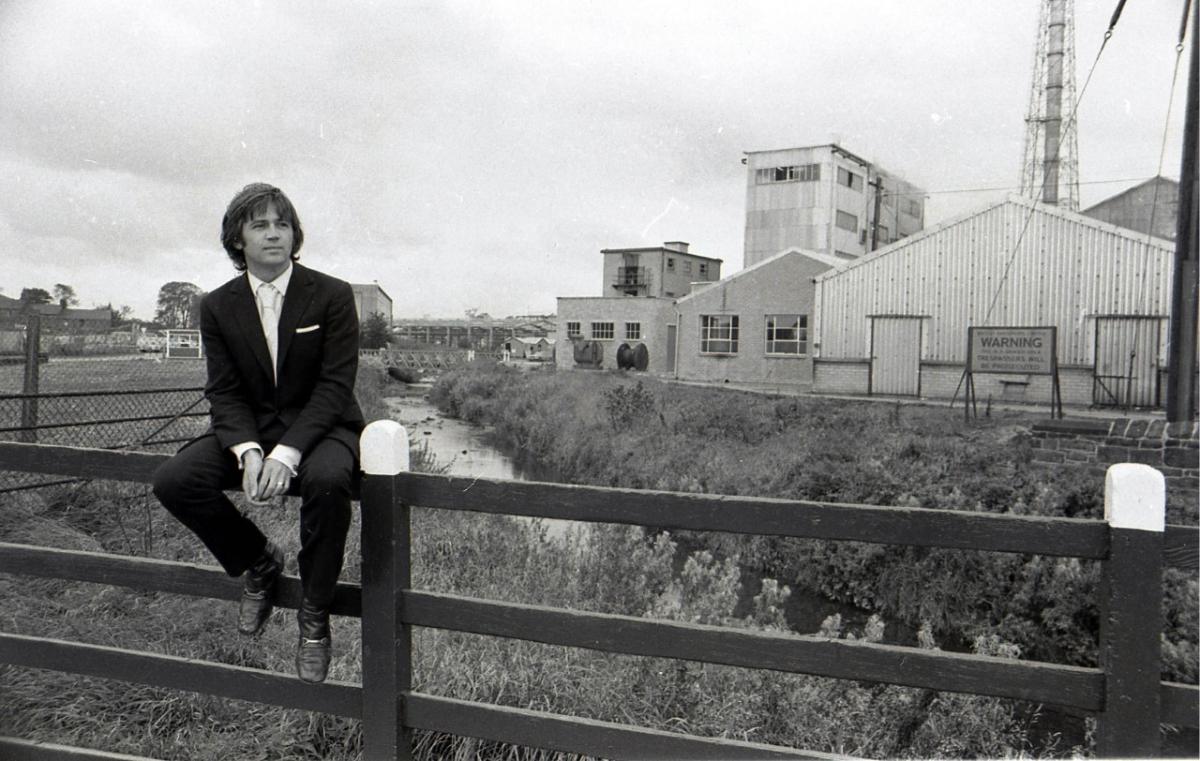

The day before his wedding, Melvyn Bragg was thinking of the past as well as the future. Memories of his Wigton childhood poured out. Those years have fuelled many of his novels and they never seem far away. “I suppose childhood was quite dramatic for my generation,” he said, talking to The Cumberland News in a lounge at The Pheasant Inn, Bassenthwaite.

“I was born in 1939. For the first six years of my life, a war was going on. My father was away. People we knew were being killed. And the blackout. If you wander around a blacked-out town every night, that’s got to affect you, hasn’t it? And yet, life went on. People who stayed made a life. With our little shielded torches in Wigton, when we went to the Congregational Church Rooms for dances and that sort of thing.

“After the war there was ration books and serious austerity. It was a different world. And I liked it very much. Samuel Johnson said ‘London has everything a man could want.’ Well, Wigton had everything a boy could want.”

How much of that boy remains in the man? “That’s one of the big questions: what you inherit and what you make for yourself. I think what I got from Wigton was the sense of the value of each individual. Although there were doctors and solicitors and the vicar, I remember feeling we were as good as anybody.

“And also the fact that you could do anything. We had swimming baths. We had fields to play in. We had these clubs to go to all the time. The idea of seizing opportunities and doing an enormous number of things was bitten in.”

An only child who grew up above his parents’ pub, the Black-A-Moor on Market Hill, Bragg was the first in his family to attend university. He has gone on to be a best-selling author of novels and non-fiction, and an acclaimed broadcaster. Since 1978 his South Bank Show has celebrated classical and popular culture, bringing insight into icons as diverse as Paul McCartney, Laurence Olivier and Marlene Dietrich.

Since 1998 he has also presented BBC Radio 4’s weekly discussion series In Our Time, in which he and expert guests discuss topics related to science and culture.

A hugely successful professional life, fuelled by a fierce work ethic. Personally, things are more complicated. Bragg has had two “very bad breakdowns”, one in his early teens and another in his late twenties. “It started when I was 13 or 14. I don’t quite know what triggered it. Either some kind of chemical imbalance or it was all too much for me. It was difficult to live above a noisy pub. Maybe it was that? I really don’t know.

“Later on my first wife and I had both got ourselves in a depressive fix. We were clinically depressed, both of us, which was awful. I think if things get on top of you and you can’t see a way out... when I was a kid I didn’t know what was happening. I had no idea who to talk to. Of course I talked to nobody. Who could you talk to? First of all, how could you describe it? Who would you describe it to? Who would listen? Then when I was in my late twenties we both went to analysts. There was somebody to talk to at least.”

Analysis did not seem to help his wife, Marie-Elisabeth Roche, a French viscountess and painter. They had been married for 10 years when, in 1971, she killed herself. “She was very ill,” says Bragg, quietly. “She was taking terrible pills that she shouldn’t have been allowed to take.”

He later became president of mental health charity Carlisle Mind, then president of national Mind. Bragg was one of several public figures whose openness about mental illness helped to reduce stigma. “The public began to understand that severe depression was an affliction. It was easy to be sorry for somebody with a broken arm. But somebody in terrible depression... they just used to tell you to give yourself a good shaking.”

He and Marie-Elisabeth had a daughter, Marie-Elsa, who is now a priest. Bragg remarried, to writer Cate Haste. They separated in 2016 after more than 40 years. “We had some marvellous times. Then it just ran out of steam. We had two terrific children, Alice and Tom.”

Three weeks ago Bragg married his partner Gabriel Clare-Hunt. The service, at St Bega’s Church, Bassenthwaite, was conducted by Marie-Elsa. “For my generation, marriage is part of our lives really. There’s something traditional about it which I like very much.”

Another landmark beckons: this Sunday, Bragg celebrates his 80th birthday. He looks much younger, but has suffered recent health problems including prostate cancer. “I’ve had 15 months of horrible bad health. And I’m not quite clear of cancer yet. But I’m well on the way. But that depletes you. I had viral pneumonia, a collapsed lung, a new hip. The cancer was very nasty. They had to wait to operate: the pneumonia depleted me a lot. Then I went in for very heavy treatment, and came through it. Just last week we went for another big check-up and I’m doing very well. Nearly through it.”

Turning 80, he says, “feels great. Life begins at 80, I’ve decided! There’s a lot I want to do. And I’m up for it. I think it’s the last big adventure. Your last phase in your life.”

His plans include more In Our Time, more TV arts programmes, more books. “I’m writing a book which is based on Wigton between the end of the Second World War and the time I went to university. That time just after the war, when it was still almost a Victorian society. A fairly battered society. Looking back on it, that time is almost like a foreign land. Nobody I knew had a telephone. Nobody I knew had a car. Very few people I knew had an indoor toilet. All that sort of thing. But there were qualities there. And I’d like to go into that.”

Bragg’s work ethic has been with him since the age of 14. School work became a focus after his first breakdown. “The idea of reading and learning was bitten in. And I’ve still got it. I love doing In Our Time. I like finding out about these new subjects every week.”

The South Bank Show, meanwhile, has revealed the methods and motivations of some of the most important figures in world culture. “I’m very proud of what I did with The South Bank Show. That I took on the establishment of the arts, and I got absolutely hammered for it. I basically said, ‘I think pop music is as great as classical music at the moment. And I think television drama’s better than stage drama.’ We also did classical music and ballet.

“Just in a major arts programme to say, ‘These are the arts now.’ To stop saying that whatever is at an opera house is ipso facto good. Because I’ve been to opera houses and it’s been rubbish. And I’ve been to pop music and it’s been much better. I’m going to follow my own instinct here. I set that out as the agenda. That was already in the air. But I think The South Bank Show helped to define it.”

On the question of whether culture is dumbing down, he said: “I think culture’s going both ways. Some culture in this country is absolutely terrific. More people are going to galleries and museums. In Our Time – look how that’s doing.

“I think a lot of the other stuff now is dumbing down. Facebook stuff is very worrying. It’s getting more powerful. More people are better educated than ever before. At the same time there’s more pornography around. There’s more instant fame around. You never know what comes of that. A hundred years ago people dismissed pop music as trash. In the last 50 years pop music has been the major art form.”

In 1998 Bragg became a Labour peer: Lord Bragg of Wigton. In the Brexit debate he is a passionate remainer, describing Brexit as “the biggest act of self-harm this country has ever done. There’s no doubt that lies were told. There’s no doubt that input was coming in from Russia. It was a fixed and crooked referendum. And we’re pretending it’s sacred.”

These were rare moments of vexation during an hour in which he seemed largely serene. “I’m very happy. My former wife and I are on good terms. I see a lot of my children. I love Gabriel very much. With a bit of luck, it’s going to be the best decade of my life. If spared.

“There’s two or three things I think I could do better than I’ve ever done. The nice thing about your eighties is, you care more than you have done because there’s so little time left. And you don’t care in another way because probably the best of your life is behind you. So what is there to lose? Maybe I’ve written the best novels I’ll ever write. Maybe I’ve done the best interviews I’ll ever do. But maybe not. So you’ve got one more decade to really go for it.

“I’d just like a few more years where I can go full pitch. And the sort of life I lead, it’s possible. I was brought up with people who worked really hard and wore themselves out. Well I haven’t done that. I’ve sat down and thought a lot and wrote a lot. That’s hard work in a way. But it doesn’t necessarily wear you out. So if I organise things properly I can have a real go.”

As for his legacy as a writer and broadcaster, he claims not to care. “I’ll be dead. They’ll think what they want. I’m glad I’ve written about Cumbria. I’ve done about 10 or 15 novels about Cumbria. About ordinary people, if there are any ordinary people. It’s been extremely unfashionable – I couldn’t be more unfashionable as a writer. There you go. I’m not going to give in.”

After eight decades, is he any nearer to answering the biggest In Our Time-style questions of what life’s about and why we’re here? “No, but I’m thinking more about it. And I think there is a meaning. I wish I could reach it. All we know is, something happened 13-and-a-half-billion years ago. What was it? Was it an intelligence or was it an accident? I’ve not the slightest anticipation of getting an answer. But I’ll enjoy thinking about it.”

One certainty is that the boy from wartime Wigton has had a remarkable life, travelling far while remaining deeply rooted. Asked if he feels lucky, the answer came quickly. “Yes. In terms of when I was born, who I was born to, and where I was born. I’ve worked hard and been lucky. That’s the thing. You need both.”

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel