Rev Matt Martinson once went six months without a shower. He was too frightened.

The Carlisle vicar had a former life as a criminal. He had convictions for drug dealing, burglary and armed robbery, and admits he was in and out of prison many times.

And he dismisses any suggestion that prison is somehow a soft option.

“It was a very horrible place,” he says. “And it’s getting worse, not easier.

“Violence is the norm. It takes an awful lot to survive.”

Matt’s recollections are at odds with the picture painted by inmates at one prison.

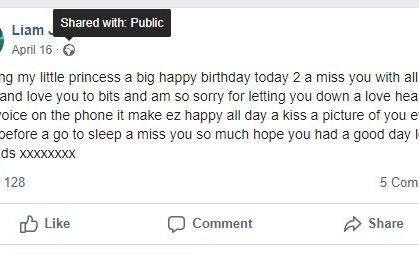

A report in The Cumberland News revealed that criminals from Carlisle at HMP Northumberland were using smartphones and posting messages on Facebook.

One inmate, 26-year-old Liam Ford, said: “I’m cushty, mate. Holiday camp here, boyo.”

In another Facebook post he is bare-chested and clutching a silver weightlifting trophy.

There may have been an element of bravado in the messages. But they do fit with a popular conception that prisoners are well catered for and prison is not the deterrent that it ought to be.

It’s not a picture that Matt recognises.

“In my experience it wasn’t a holiday camp,” he says. “Every sentence got harder.”

Matt’s last spell inside was four years in HMP Wold in east Yorkshire. During his time there he became a Christian and on his release he trained as a clergyman.

He is now married with a son and last month became vicar of Holy Trinity, St Barnabas’ and St Luke’s churches in Carlisle.

He’s a changed man. But his memories of prison are vivid.

During the course of his earlier life, Matt served time in all categories of prison and says: “You never feel safe. Even going back as a visitor or a chaplain I don’t feel safe there.

“There was one jail where I didn’t take a shower for six months because I didn’t feel safe to do it.

“You can never trust anyone in prison. There are guys who seem reasonable and the next minute they could stab you in the back, literally.”

He notices that it has changed – for the worse. “They have done away with slopping out. But the level of violence is increasing. You could get killed for a £2 bag of heroin.”

Mandatory drug testing, he believes, has increased the violence. It has made fighting over heroin more common.

“Cannabis stays in your system longer than heroin,” Matt explains. “A lot of people who were cannabis users switched to heroin because it was harder to detect.”

He’s not arguing against prisons. “We do need them, because there are certain people who, no matter what we do, have to be locked up for the sake of society.”

But there needs to be reform. “There are cells designed for one person where we are locking up two or three people.

“There’s a lack of funds and a lack of staff.”

Re-offending rates are lower among offenders who are given community punishment orders, and he says: “We need to look more at community punishments, and give more support to offenders when they are coming out, to make them less likely to re-offend.”

Mick Pimblett was a prison officer in the north of England for 30 years and is now assistant general secretary of the Prison Officers’ Association.

Over his years in the service he saw prisons become more brutal places – and agrees with Matt that they are far from holiday camps.

“Violence is the main issue and it’s getting worse and worse,” he says.

“There are 28 prison officers being assaulted in prisons in England and Wales every day. Among prisoners it’s much higher.

“Even in open prisons we’re seeing increased violence. In the last nine years 8,000 prison officers have left.”

There’s one main reason for the increase. “Drugs are widely available now, prisoners are very innovative about finding ways of getting drugs and they are very difficult to intercept.

“Sometimes they’re just thrown over the wall. That jail in Northumberland has the longest boundary in the country and it is impossible to police it.”

He explains: “Prisoners get into debt over drugs and the debt is often settled by violence. So drugs fuel the violence.”

The violence is not confined to men’s jails. “It’s across the whole estate. In women’s prisons, like Low Newton in the north-east, it’s as bad as anywhere else.”

Criminal gangs also operate inside. “They exist in the community and they get formed up in prison,” Mr Pimblett points out.

“One gang will try to take over the drug dealing within a prison. We try to keep the gangs separate, but with a shortage of accommodation we can’t always do that.”

But he is convinced the problem of violence could be reduced if there were more prison officers. The Government boasts of 2,500 more recruits – but more than three times that number have quit since 2010.

“When I started you would have 180 prisoners and 12 officers. Now you have 180 prisoners and six officers.

“The prison service is supposed to offer some rehabilitating, but all we can do is manage the population. They are like warehouses.”

Helen Berresford observes that much of the violence in prisons is inflicted by prisoners on themselves.

She is director of external engagement with the National Association for the Care and Resettlement of Offenders (Nacro), and says: “The recent ‘Safety in Custody’ figures by the Ministry of Justice tell a story of a broken prison system, with incidents of self-harm at a record high – 57,968 people harmed themselves over a 12-month period.”

Of course prison is not supposed to be pleasant. But the hope is that those who serve a sentence don’t end up back there and Ms Berresford argues “high levels of self-harm, drug abuse and suicide within our prisons show that in many cases they are not helping to prepare people for a better life upon release, and could contribute to an increased risk of re-offending”.

Like Matt, she feels a different approach is needed to reduce it.

“At Nacro, we see how critical the first few hours and days after release are.

“We all know that having somewhere to live, a job, good health and connections mean someone is much less likely to commit a crime. But currently around 1,000 people a month are released homeless from prison, some with only the clothes they are wearing and £46 discharge grant.

“Giving people the best chance benefits us all – it reduces crime, builds stronger communities and leads to a criminal justice system that people can trust.”

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here