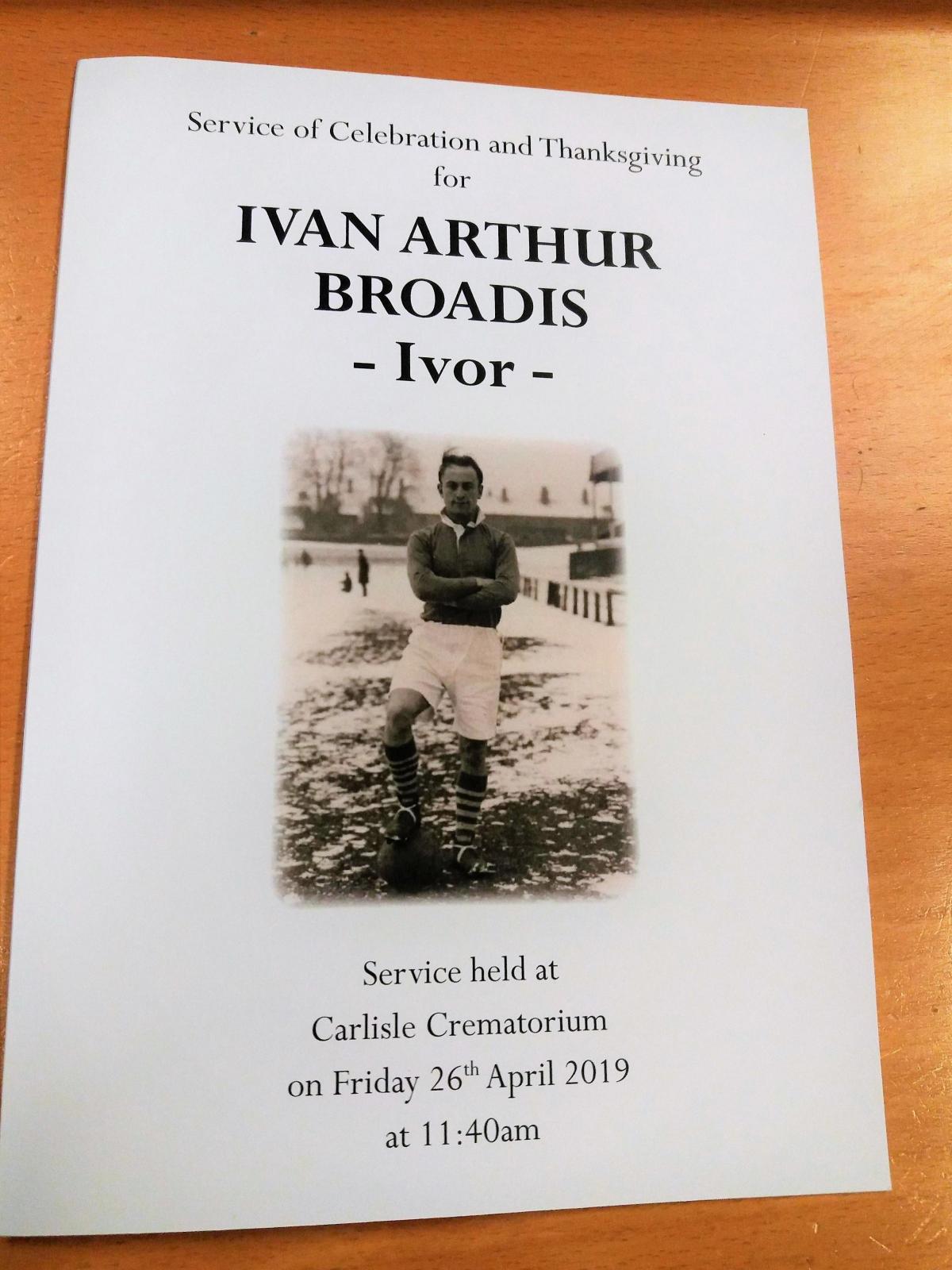

Two England caps, blue velvet with golden trim and tassels, balanced gently on Ivor Broadis’ coffin as his funeral hearse drew alongside the crematorium.

One marked his selection in 1954 to face Hungary. Another commemorated a friendly against Italy, when Broadis scored his first international goal.

A floral football also accompanied him and, when his coffin was carried into the building, and dozens of mourners filed inside, Louis Armstrong’s rendition of ‘Blue Moon’ played over the speakers.

Distinguished in death, as in life. Ivor was bade farewell in his adopted city today, and his family’s wish that his funeral would be a celebration as much as a solemn parting had already been achieved through many warm memories and tributes before celebrant Benet Waterman invited everyone to stand and applaud.

They clapped with gusto for perhaps the finest football man Carlisle has known; a person of wide and varied talents; a father, a husband, a family man. Someone of high public standing and private appreciation. A unique figure of several eras.

Someone whose like might never pass this way again.

Before Ivor’s arrival, a sunny and breezy morning had been accompanied by the hum of reminiscence. Alongside family and friends there was a number of old footballers, some white of hair, some stately of movement.

It was like peering into a dressing room of the past as, from Carlisle United’s pomp, George McVitie, Peter Garbutt and Joe Dean held court. Hugh McIlmoyle, straight-backed and elegantly suited, was beckoned to join them. Laughter quickly emerged from this cheerful quartet.

A Queen of the South blazer reminded us that Ivor, as well as gracing Carlisle, Manchester City, Sunderland, Newcastle and his country, had taken his gifts across the border. His standing in the North East was underlined when a black car pulled up and Peter Beardsley got out.

From Brunton Park, co-owner Steven Pattison and community sports trust manager John Halpin paid the club’s respects. They were in the packed main room, while others occupied the overflow chapel. After Ivor’s coffin had been carried in by his pall bearers – McVitie, Jazza Boyle, nephew Hilton Sanderson and his son David, Richard Telford and Keith Phillipson – the formal process of remembering began.

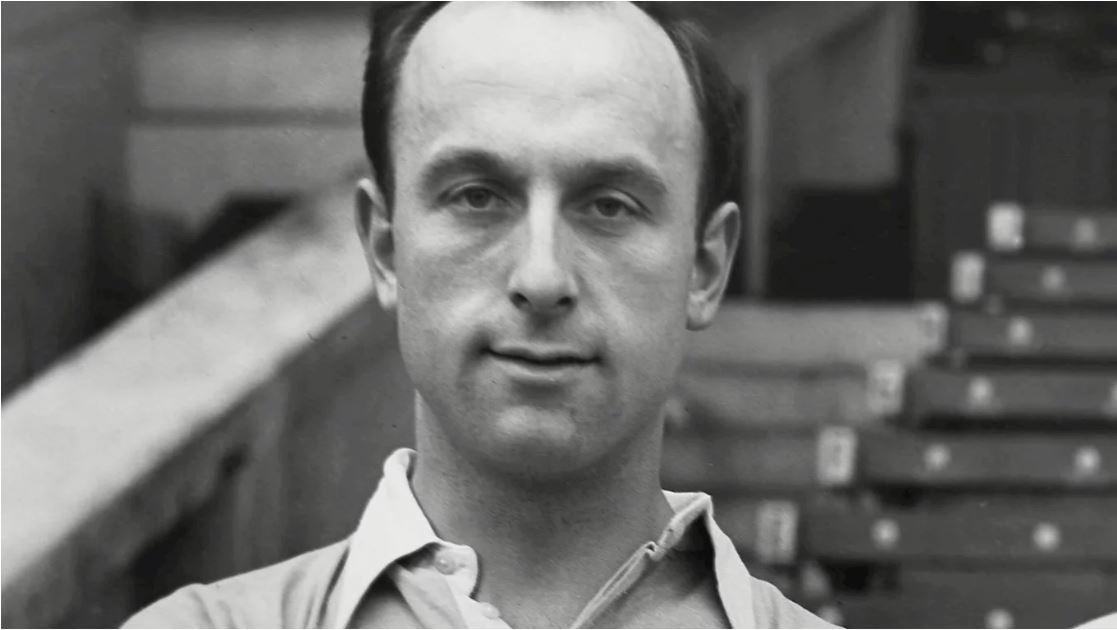

“He has lived so many lives in one,” said Benet Waterman, and each demanded proper reflection. It was recalled, for instance, that before his football reputation flourished, Ivor had completed 500 flying hours as a RAF navigator in World War Two.

This included the guiding of troops back to England after conflict’s end. Ivor’s own first-person memories were recounted, there not being a “dry eye” amongst the soldiers as he told them their plane was above the white cliffs of Dover.

When it came to football, his immense career was carefully laid out: his early days with Finchley and Northfleet, the registration mistake at Tottenham which turned Ivan – his real name – into Ivor. His appointment as Carlisle’s player-manager at just 23, still a record, after his posting to Crosby-on-Eden’s airfield. His decision to “sell himself” to Sunderland; his regret that the “Bank of England” club of Roker Park did not win the league in 1950. His £12 weekly wages in an age when “the only agent was Dick Tracy”.

His service as an inside-forward at Maine Road, St James’ Park, Brunton Park again, and Palmerston Park. Fourteen international caps and eight goals; England’s only scorer in their 7-1 defeat by the mighty Hungarians, the first man from these shores to net twice in a single World Cup match, the six-figure crowds against Scotland.

As a journalist, Ivor was also praised, for papers in Manchester, the North East and Cumbria. Ivor was not just a sharp football writer but a “staunch ally” for players embroiled in contract issues. “His words were not always what club boards wanted to hear,” but he was strong and sincere. He also interviewed the Beatles in Carlisle while, in the latter stages of his 96 years, he would waive fees for being interviewed himself, preferring causes such as the motor neurone disease appeal in Tony Hopper’s name to benefit.

Ivor was also “the heart” of his family. We heard of Joan, his wife, and their wedding which was significant enough to close streets in Carlisle. Son Mike, who passed in February, was recalled while, through the celebrant, daughter Gill painted pictures of Ivor at home, in his allotment, or, as a skilled cook, in the kitchen, whipping up steak and kidney pies, meatloaf, damson trifle, sloe gin. More than once had Tom Finney, another England football icon, visited to sample the fayre.

Towards the end of the service, thanks were issued to those who had helped and given: Hospice at Home, the Cumberland Infirmary, the supporters of Carlisle United, who had given Ivor a minute-long ovation at their last home game.

As those in the enclosed crematorium repeated that applause, two framed, commemorative felt badges, showing England’s Three Lions, also rested against his coffin, which was committed to ‘Wind Beneath My Wings’ by Bette Midler. David Harkins’ poem, ‘He Is Gone’ (“You can shed tears that he is gone, or you can smile because he has lived…”) was read, and as people walked out, Monty Python’s ‘Always Look on the Bright Side of Life’ played.

This meant, fittingly, that there was cheer, as well as sadness, as the great Ivor Broadis took his final leave. It was drizzling by now, but the sun was still nudging brightly through the clouds.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here