It’s daft, expecting to see something unusual in Kenny Stuart. Some clue that reveals the source of extraordinary powers, that makes you think “Ah – so that’s his secret!” Daft... and hard to resist.

Kenny is small in stature – 5ft 5in – quietly spoken and a little cautious before relaxing during an hour of conversation. Not extraordinary. Ordinary, in the nicest way. But his front room in Threlkeld is not really the place to understand his talents. And 2017 is not really the time.

We have to go back to the 1980s to see what was special about Kenny. When he powered up hillsides while rivals tried vainly to hang on. When he glided over stony ground in style. When he was young.

Kenny’s house is 100 yards from the one he grew up in. He played and ran on the surrounding fells, a long time ago now. Last month Kenny turned 60. Does he feel it? “Not at all,” he says. “But when you look back you realise how many years it is.”

Here are some of the reasons Kenny Stuart is rated alongside Joss Naylor and Billy Bland at the pinnacle of his sport.

In 1985 he became the first man to win the British Fell Running Championship three times. He set records in classic races such as Ben Nevis, Snowdon and Skiddaw, records which still stand. He switched to marathon running, proving successful there too.

And then the dedication that brought Kenny here backfired. His immune system “crashed”, as he puts it. He was overwhelmed by tiredness. In his early thirties he quietly retired from running and has worked as a gardener ever since.

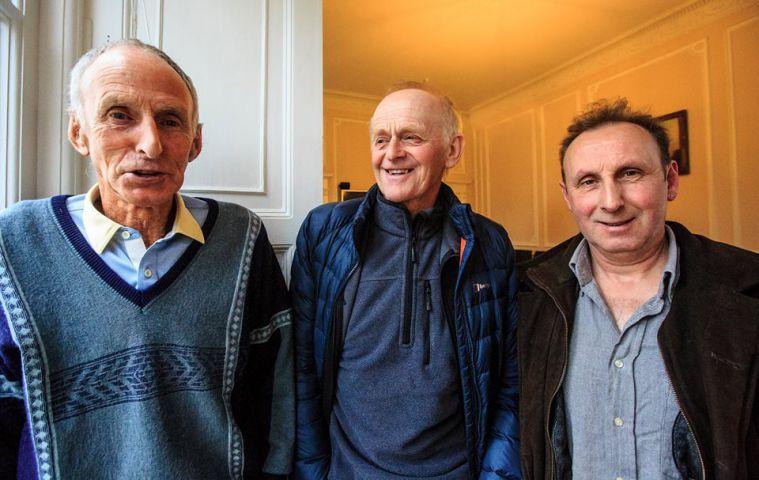

Kenny Stuart Even at his peak Kenny was not a household name. Fell running’s rewards have never matched its demands. But in recent years a small library has been written about the sport; evidence of our fascination with those who exceed normal limits.

One new book by Steve Chilton – Running Hard: The Story of a Rivalry – puts Kenny centre stage. It looks at the 1983 season, the most closely fought in the sport’s history. The rivalry concerns Kenny and John Wild, an RAF serviceman from Derbyshire, who had been fell running champion for the previous two years.

All season they matched each other on hills across England, Scotland and Wales. The championship hinged on the final race. Kenny won it by 20 seconds and claimed the crown. His understated celebration typifies a sport which despises showiness.

In Running Hard he says: “I think we just had a drink and a coffee and a sandwich maybe and just set off to drive home as normal. There was no big deal about it.”

Kenny retained the title in the next two years, winning nearly every race he entered. “At times I felt like I was gliding. At other times my legs felt like bloody lead!” On those days he often fooled rivals into thinking his tank was full. So many tests of body and mind.

Kenny picks out his record-breaking win at Ben Nevis in 1984 as perhaps his greatest day. He remains the fastest person to run up and down Britain’s highest mountain. Fit walkers take about seven hours. Kenny hit the finish line in one hour 25 minutes.

He recalls “a very, very tough race. I got halfway down and I heard what sounded like a bulldozer behind me. Jack Maitland went past me like I was standing still. I had to come back at him. By the time I hit the road I was back in command. I always had an extra gear when I hit the flat, which made a big difference.”

How did he handle the pain of pushing so hard? “I don’t think it’s actual pain. It’s tremendous discomfort.”

Most of his work was unseen by the thousands who watched races. Kenny trained twice a day: a brutal regime of road, fell and forest. He fitted this around his job as a gardener at Keswick’s Hope Park. “In winter most of my training had to be done on tarmac. The A66 wasn’t so busy then. We used to call it ‘running the white line’. I didn’t even have a head torch. When you saw headlights you’d get into the side.

“You’d go to extremes just to get your run in. At St John’s in the Vale the road was blocked with knee-deep snow. A snow plough was trying to get through, and I was ploughing through it! The man in the snow plough was shaking his head.”

Kenny does the same after telling this story. He mutters “Obsessional behaviour.” What does he think about it now? “Absolutely crackers.”

At the top of Snowdon one year he and many other runners suffered varying degrees of hypothermia. They were shaking so much their coffee cups were empty by the time they reached their mouths.

This life breeds camaraderie. Runners show rivals around their local course before races. Running Hard reveals nights of post-race refuelling: mooning on stage during presentation ceremonies; nude relays; how many fell runners can you fit in a revolving door?

“We wouldn’t get away with it now,” smiles Kenny, adding that he doesn’t think he ever stripped off. His party piece was belting out hunting songs.

He skinned his feet winning the 1983 Borrowdale race, then danced the night away. Perhaps he didn’t need to live like a monk.

“In late 1984, I wasn’t socialising. I wasn’t married. I had nothing apart from work and training. I decided I would allow myself to go out on a Saturday, have four or five pints and relax. It would be something to look forward to at the end of the training week. In ’85 I ran a lot better for that.”

Kenny won his third straight British championship, then turned to road running. He won his debut marathon at Glasgow in 1986 and ran a world-class time of two hours 11 minutes at Houston three years later.

By now he was married to Pauline, herself a fell running champion. Home life was happy, professional life less so.

Kenny had stopped working as a gardener to be a full-time athlete. But his body was rebelling. He says: “I was a born hill runner. It felt easy when I was climbing. I was only eight stone wet through then. Marathon training was more difficult. There’s no break. There’s no ‘I’ll just come down this little bit of hill a bit slower’.”

Kenny Stuart Kenny had always been prone to viruses. These became more frequent. In 1990 he tried to train through another but failed to shake it off.

“I couldn’t drive a car more than 30 minutes without getting tired. The virus, or whatever I ended up with, probably wouldn’t have come out if I hadn’t pushed my body. It’s that same obsessional thing – trying to run through an illness. Nine times out of 10 it worked. Then my immune system crashed. It’s nature’s way of stopping you from doing permanent damage. If you’re training the way we trained, it’s bad for you. No one can tell me it’s natural.”

Tests never found a definitive cause of Kenny’s malaise. Whatever the reason, his days at superhuman heights were over.

He says: “I’d have loved another two or three years at the marathon. But if someone had said at 16 ‘This is what you’re going to do, but you’re going to end up like this at 35’, okay. I’ll take that.”

He returned to gardening and is now self-employed. His three children competed in junior fell races but none pursued the sport into adulthood.

Their father gave it another crack years later, to see if anything was left. Kenny ran at a few local events, winning some but often feeling drained afterwards. His last was at Ambleside. He was 47 and training lightly, by previous standards. “I was fairly fit on 20-25 mile a week. At the start I just looked around. I didn’t feel any nerves. I had no adrenalin. I thought ‘No, it’s just not there anymore.’”

In some ways that was the end of Kenny Stuart. Today’s Kenny is someone else, says the man in the Threlkeld front room. “I wouldn’t describe myself as a runner now. Running is almost like something that was another Kenny Stuart. You almost have to nip yourself to remember you were there.”

Photographs on the wall show that other Kenny Stuart still leading the pack. Memories pour in when this one opens the curtains and sees fells he used to glide up. Blencathra towers behind the house. “Now you look at it and think ‘Goodness!’”

He still ventures onto the fells, with the Blencathra Foxhounds foot pack. “I enjoy walking more than I ever did running,” he admits.

“I’ve got an interest in wildlife. You’ve time to stop and look.”

Kenny sounds mortal. Perhaps he always did, even in his former life when the curious passed this way seeking solutions to the great man’s mysteries. “People would always ask about your training regime. They always seemed disappointed with what I told them. They were looking for some magic formula. There is no magic formula.”

Just talent and graft. Reach your limit then push harder. As simple, and as complicated, as that.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here