Stinky Bill Watson has a lot to answer for.

But the former chemistry teacher at Workington Grammar school would be proud to take even the slightest credit for Paul Workman’s career.

It was Bill’s lessons in chemistry (the tell-tale evidence of his experiments were responsible for his nickname) and Polly Barnes, who taught biology, that fired up young Paul’s love of the subjects.

It is a fascination that continues to burn brightly many decades later in labs that the schoolboy would have regarded as science fiction.

Places where he has made many notable breakthroughs in the battle against cancer.

Rather than medicine, the teenager wanted to take up this new subject called biochemistry at university and was intrigued by what was happening to tackle the killer disease.

His interest became personal when his dad, John, who worked in the Workington steelworks, was diagnosed with inoperable bowel cancer.

Paul was 23 and in the first year of his Phd. John died a year or so later, when he was 55. An only child, the pair were very close and he says flatly: “There were no real drugs. He never got to my wedding or see his grandchildren.

“I had an intense scientific curiosity, an interest in medicine and an intense personal experience with my father early on in my career. That cemented my motivation.”

There was more personal motivation in the battle when his mum Ena later died of cancer aged 68.

With a dad in the steelworks and a grandad who had been a miner, young Paul was the first in his family to go to university. But the desire to produce something had been handed down in his genetic code.

Making breakthroughs in the lab are all well and good, but transferring that work into a treatment that can change or save lives is Paul’s goal.

He has even set up his own companies to produce some of his discoveries.

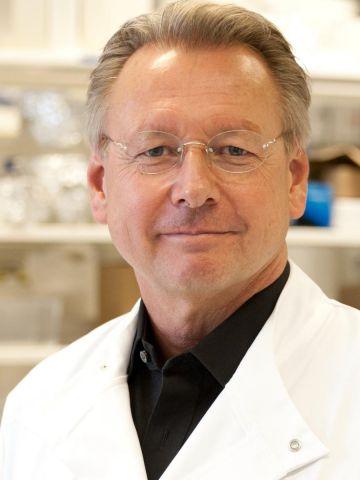

A superstar in his field of medicine, he has pioneered crucial new approaches to tackling the disease and leads the UK’s fight against it as chief executive and president of the Institute of of Cancer Research (ICR).

He discovered personalised treatments that are precisely targeted to the DNA code of each individual.

The 65-year-old says it is a “privilege” to carry out the work and despite his high-powered position as leader of a world-renowned organisation, he still feels the need to lead teams of scientists in the search for new breakthroughs.

During his 40-year career, he has played a significant part in helping double the number of those who survive the illness.

“I have been very lucky. I chose a field where there was a huge amount of progress to be made,” he says modestly.

“As we all live longer, one in two of us will get cancer, but 50 per cent will now survive for 10 years or more.

“There is still a great deal to do. Some cancers like pancreatic, brain and lung still have patient survival rates of 10 years that are less than 10 per cent.

“What excites me is discovering things and applying that to cancer treatments.”

One of the most recent breakthroughs has been to discover the genetic causes of the most common cause of brain cancer.

Another is the development of a computer programme that can identify women at high risk of suffering a relapse of breast cancer.

Prof Workman says that developing such computer programmes is a major area of development in the battle against the illness.

The brain cancer breakthrough was made by studying more than 30,000 people with and without the cancer, with the help of colleagues in the US and Europe.

A keen football fan, Paul supports two teams of reds – Workington Town and Manchester United.

He has been responsible for building and leading several teams of his own in drug discovery and development and admits former United boss Sir Alex Ferguson is a hero.

In the early nineties, Prof Workman lived ‘round the corner’ from the legendary manager.

The scientist had been appointed head of the cancer research bioscience section of AstraZeneca pharmaceuticals at their site near Alderley Edge in Cheshire.

In 1997 he moved to the ICR to take over and build up the Cancer Research UK Cancer Therapeutics Unit.

He was unit director for 18 years until taking over overall leadership of the organisation.

His achievements are too many to list here in full. He is a Fellow of the Royal Society of Chemistry and of the Royal Society of Medicine.

In 2012, he was given the Chemistry World Entrepreneur of the Year Award by the Royal Society of Chemistry is recognition of his success at taking pioneering drugs out of the laboratory and into commercial development for the benefit of patients worldwide.

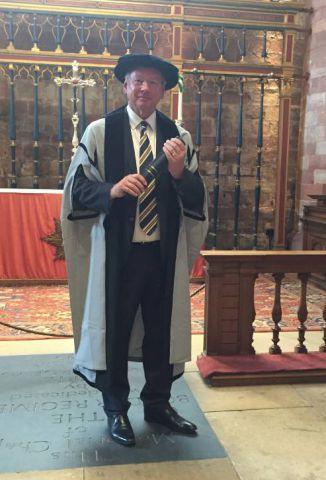

His latest accolade was to be named an Honorary Fellow of the University of Cumbria.

At his acceptance speech last month, he dedicated the award to his parents and revealed how a visit to Eden Valley Hospice and the Jigsaw Children’s Hospice that morning had provided added inspiration and impetus to his work. He said: “This was a strong reminder of how much work we still have to do to – at the Institute of Cancer Research and elsewhere – to cure cancer in both adults and children.

“Only the other week, a patient said to a colleague of mine; ‘don’t stop, keep going – I’m still alive because of the work you do’. That’s great motivation.”

He fears that Brexit could make it difficult for the ICR to continue to recruit top foreign researchers and scientists to any future teams.

“Cancer does not recognise or respect geography or political boundaries,” he points out.

“Some 50 per cent of people regardless of race or nationality will get cancer. If we are going to overcome those illnesses it is absolutely essential that we can recruit to the UK the brightest and the best from around the world and Europe.”

He still spends time leading research teams in the lab and slipping into Sir Alex mode, he points out: “In order to do the best possible research, you need a super team, just like football.

“It has to be well led, tactically aware, strategically focussed and have all the talents in the different positions.

“You need the ideas of people in different areas of science to crack the problems we face. Every member of these teams has to be top class and you have to go all over the world to get them.

“Individual people will have fantastic ideas, but you need a team of brilliant people to make progress.”

He reckons a quarter of those who work at the ICR are foreign scientists and a “high proportion” are from continental Europe.

“We have seen a dip in the number of people applying from Europe since the uncertainty caused by the Brexit vote,” he admits.

The Workington lad moved away from Cumbria long ago and now lives with wife Liz near Guildford, in Surrey, their two children have grown up but there are two young grandchildren to keep him on his toes.

He and Liz go walking in the nearby hills, but they don’t compare with the Cumbrian fells he left behind in the seventies.

“I used to do a lot of hill walking and folk singing in the pubs when I was younger and I do enjoy the hills very much, but I don’t miss the rain.”

Back at work, the biggest challenge facing his teams now is drug resistance. Cancers have the ability to evolve and we have to try and keep up or ahead of them.

After all these years, all those breakthroughs and so much achieved, he is as driven as ever.

His new goal is to establish the London Cancer Hub – a world-leading science campus specialising in cancer research, treatment, education and enterprise.

He has won £30m worth of Government funding for a new £75m drugs discovery building and is creating a £100m biotechnology campus which will be known as the London Cancer Hub, combining research with biotech businesses and creating cancer’s version of Silicon Valley.

The project is expected to create more than 13,000 jobs and will deliver at least two extra cancer drugs every five years, generating £1billion a year for the economy.

A man of vision and a man of action, he says: “I’m often asked about those ‘Eureka!’ moments.

“I have been involved in 20 drugs getting into the clinic, but the thing I am most proud of is when you can see that drug getting into the patient for the first time and their tumour getting smaller.

“I’m also proud of the teams I have assembled and the science we have done.”

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here