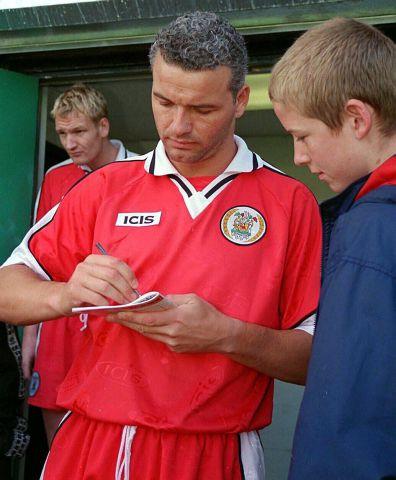

On a drizzly day in Blackpool, Paul Stewart offers a warm greeting. His curly hair is now grey but he still looks familiar as the top-flight player who spent two surreal seasons in Cumbria, with Workington Reds, at the end of a career studded with achievement but dogged by personal trauma.

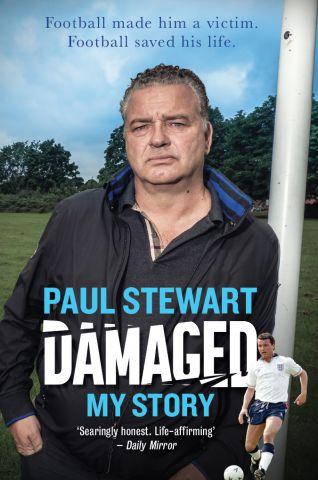

Stewart proves easy to interview because he talks so freely - as he has since the publication of a darkly engrossing autobiography. Damaged reveals the extent of Stewart's sexual abuse as a boy by the predatory football coach Frank Roper, and the ways that harrowing experience poisoned parts of his adulthood.

Our conversation flows in the presence of a small white dog, which scratches at my leg, and Stewart is more at ease than he had seemed when first going public about his story last November. Then, television interviews saw him tearful.

"You've got to remember," he says, "I came out of the game 20 years ago and went into obscurity. So being back in the public eye was difficult at first. The initial few months, my emotions were up and down like a rollercoaster."

Stewart bravely waived his anonymity, in a Daily Mirror interview, as the highest-profile of several former players to shine light into a grim corner of the game's past. Among the most haunting revelations in his book, published nine months later with the intention of helping others, are that Roper's abuse, conducted over four years in the paedophile coach's car when Stewart was aged 11-15, left him barely able to speak for a full year of his junior life.

Later Stewart was afflicted by depression and, in attempts to smother his secret, relied on alcohol and Class A drugs even at certain points of his football height.

Stewart is now more enlightened about his state of mind. He does not drink as he used to, while he has not touched cocaine for several years. He also stresses he does not "walk around with a cloud over me all the time, far from it" - yet depression remains a challenge.

"There are still dark days and there are good days," he says. "Even whilst writing the book I suffered with issues again. But I've learned to manage it. I know there isn't a magic wand."

I ask about the darkest of those days and he answers candidly. "Right to the point where I just wanted to call it a day. You end up thinking of ways to do it. Whether that's going in the car and driving off the end of the pier, hanging yourself, taking tablets, or whatever. You're not in a good place."

Stewart says he never carried out these intentions because he would think of the impact on his family, who have been staunchly supportive since he confided in them what he suffered at Roper's hands. At 52, he also believes having an older head helps him better interpret his thoughts. "I used to find solace in books, too, books like mine," he adds. "And then I'd think, well, there are people worse off than you, Paul. And that would help me snap out of it."

He draws on an e-cigarette. "It's not, though, one of those illnesses you go to bed and wake up with. In my experience it creeps up on you, and suddenly you're in a state where you can't think rationally.

"Now, if I feel I'm going through something, I try and talk to my wife. I still struggle with that, but the last time I managed to text her: 'I don't know what's up with me, I just don't feel right.' And it didn't manifest itself into what it has in the past."

Stewart's unspoken past as a victim of abuse accompanied him through a football story that appeared golden. This included his goal to help Tottenham win the 1991 FA Cup final, a dream move to Liverpool, three England caps, and even his unexpected move to Workington, in the North West Trains League in 1998, where he helped Reds won the title in his first season.

He smiles when invited back to those unlikely days. "I thought, when I left Stoke at nearly 34, that was going to be me finished playing. Then Bill Wilson [the Workington chairman] contacted me. I had no aspirations of playing non-league, and when I got the train to meet them I still wasn't sure. But Bill sold it to me."

Stewart was a remarkable coup for the Borough Park club. Attendances rose by hundreds and, although not always injury-free, he played with commitment and echoes of his old ability in a team whose work ethic engaged him.

"From the start," he says, "I was taken aback by the passion of the players. Some of them were working nights and then coming to play without any sleep.

"As a professional, if we'd played on Saturday and were asked to come in on Monday, we were moaning. It showed me what an arse I had been. The enthusiasm of the Workington guys gave me some passion back for the game."

The Wilson era eventually ended controversially, for the subsequent regime claimed the club was saddled with debts. In 1998, though, the fall-out seemed a long way off. "Bill was just enthusiastic," Stewart says. "I didn't have any idea what was going on with the finances, and in the end it transpired that he wasn't doing the best by the club - but on the surface it looked like he was doing a good job. The supporters had turned up, and we won the league."

A 13-game winning run under manager Peter Hampton led to a jubilant deciding game of 1998/99, against Mossley, 2,281 people swelling Borough Park. Stewart limped off after 15 minutes and his replacement, a teenaged Grant Holt, scored the decisive goal in a 2-1 win that clinched Reds' first-ever league title.

"Some of the games were tough," says Stewart. "We had to grind out results. But the team spirit kept me going - as did the Workington people. They opened their arms and took me in. I think I did it on the field for them in that first season, which always helps when you're going into a town with the reputation I had. And the day we won the league was brilliant."

Stewart feels there was talent in that Reds side that could easily have gone further, had scouts taken interest. One who did make it was Holt. "I remember him being quite fast, but skilful. He had an eye for goal, and you can't buy that."

In his book Stewart says he was offered the post of player-manager at the end of a less dramatic 1999/2000 campaign, but he did not yearn to remain in football - and nor were his body and mind in good enough harmony. Even in west Cumbria, the emotional legacy of Roper was again catching up.

"In that second season, I was socialising more, it was lending itself to drink and drugs, and I wasn't prepared to take more money out of the club when I wasn't committed," he adds. "I felt it was only right that I ended my career totally. I wasn't doing justice by Workington or by myself."

Stewart says his immediate life out of the game left a void where he further leaned on the wrong solutions. It took courage and determination to come out of that hole, with the support of wife Bev and a family without whom, he repeats, he would probably have "ended it all".

In case this risks painting a narrow picture, Stewart again says that he is far from permanently depressed. He now runs a digital signage company which operates in several countries, while his seven-month old granddaughter Sienna brings a smile to his face. "She's beautiful."

He is also doing positive work with three fellow players who were also abused. David White, Derek Bell, Ian Ackley and Stewart have formed SAVE (Safeguarding And Victim Engagement), which aims to bring welfare higher on the agenda at professional and grassroots clubs.

Stewart believes, among other things, that police checks should be more rigorous, that committee members at junior clubs should go through the same safeguarding procedures as coaches, and that sanctions should be imposed on clubs who do not follow codes of conduct. "I don't think we'll change things overnight. I initially told the FA they were burying their heads in the sand. But, since meeting them in December, I feel we have made some big steps."

Roper, who died in 2005, targeted Stewart and other boys in the north west during a less regulated age, also befriending their families to further disguise his true nature. "People are more aware now, but let's not be naïve and think it doesn't still go on," Stewart says. These men [abusers] look at other avenues. If they were businessmen they'd be really good, because they are clever. We just have to find as many ways to stop them as we can."

His work with SAVE helps Stewart look forward as well as back. His football memorabilia, including his Reds medal, is stored at home rather than displayed, while he cannot know whether this period of disclosure will alter him. "I have to let other people make that decision. Some acquaintances find it quite difficult to approach me, because of the subject matter, but I've tried to put them at ease by saying I haven't changed one bit. I'm still Stewy. I'm still the same guy."

Perhaps understandably, Stewart has not set major goals for the next phase of life. "What's happening now is interesting, and keeping me busy, but sometimes you can strive, and strive, and when you get there, what have you strived for?

"One can only say that you look for happiness. That in itself is maybe a little bit difficult for everyone. Life isn't that simple."

*Damaged: My Story by Paul Stewart with Jeremy Armstrong is published by SportMedia, priced £18.99

*For more information on SAVE, visit www.saveassociation.com

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here