POLICE in Cumbria are dealing with a growing number of mental health related call-outs due to a “vicious circle” of reforms and lack of resources.

Officers say the number of alerts they have to deal with are going up – a situation mirrored nationally.

But the demand has prompted concerns from the organisation representing rank-and-file officers, which has called for a review of the allocation of resources.

Senior officers have also spoken about the situation.

Chief Superintendent Mark Pannone, the force’s leading officer on mental health, said: “There is no doubt that the number of mental health incidents by month that we are dealing with is on the rise.

“The number of incidents going up on one level could be interpreted as a positive – in as much as people feel confident to contact the police and believe that the police are able to help them.”

In December, the force dealt with 377 incidents relating to mental health, a total way above the five-year average of 220.

In 2016 as a whole, officers also typically handled between 250 to 350 incidents a month – again above this average.

By comparison, in December 2012 there were 185 incidents.

As people are encouraged more and more to talk about their problems, Mr Pannone believes an increased number of people are prepared to look for help, which is why further incidents are being reported to the force.

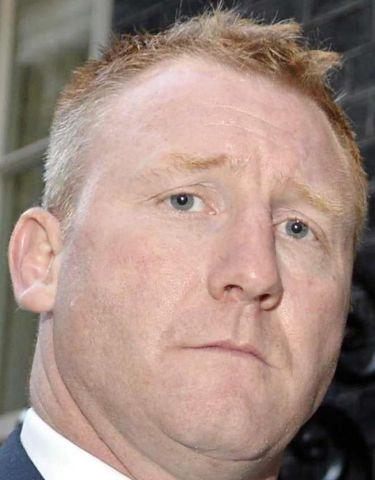

Martin Plummer, chairman of the force union, Cumbria Police Federation, said it was good to see the public confiding in the police.

But he added that police reforms and reforms in other emergency services had a knock-on effect on the type of incidents police were dealing with.

“It really is a vicious circle,” he said. “Unless there are reviews of the resources allocation, then this is only going to get worse.”

Mr Plummer thinks a review of emergency services is vital to look at what needs to be done to help a process he said is “very quickly going down hill.”

“We are having to do the very best that we can,” he said.

“Sometimes that means transportation in police vehicles and places of safety within custody suites. That cannot be right.”

Though officers are trained in relation to mental health, they are not trained in the same way as mental health professionals and sometimes those with the appropriate training aren’t available.

Mr Plummer said these situations can be distressing and a further problem for people with mental health issues. It also means that a backlog is created as calls come in on jobs they are trained to deal with.

“People with mental health issues who come into contact with the police typically come into contact because they are in crisis and they feel that there’s nowhere else for them to go,” said Mr Pannone.

He added: “There are many agencies and charities that are really helpful for people to speak to.

“What we are seeing in the constabulary is an increase in the number of incidents that are dealing with that are mental health related. We have seen this increase over the last few months.”

The issue of police resources has been regularly in the spotlight in recent years.

There have been reforms in the way the force operates, although these have sometimes been controversial.

Last week The Cumberland News revealed how thousands of attempts to get through to Cumbria Police on the 101 number were being abandoned.

Figures last year also found nearly 25 per cent of callers had to wait more than six minutes for someone to pick up the phone.

On mental health, Mr Pannone stressed that the partnership working between the police and the Cumbria Partnership NHS Foundation trust is better than it has ever been.

But those in crisis – at risk of suicide – are contacting the police as their first point of call. The force is conducting research alongside the trust to look at why the police are contacted for mental health incidents.

Cumbria Police has dedicated mental health liaison officers who work with the partnership trust and crisis negotiators who will engage with those in crisis and work to protect their life.

“Sometimes people are a danger to themselves or others,” said Mr Pannone.

“We have the power under the Mental Health Act to take these people to a place of safety and to ensure they get the support and the care that they need. That can be quite time consuming but sometimes it’s necessary for the police to get involved in those incidents.”

For support about a mental health issues contact the Samaritans on 116 123, MIND on 01768 899 002.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here