Rory Stewart politely declines to offer an opinion on president-elect Donald Trump. The UK’s Minister for International Development is meeting The Cumberland News to discuss his new book, The Marches . He is in no mood for an ambush.

The next half hour may not reveal what Stewart thinks of Trump’s plan to build a wall along the Mexican border. But the effect of walls? The Marches includes plenty on that topic.

The book has three main strands. There is a walk along Hadrian’s Wall, undertaken in 2011. There is a walk the following year from his home near Penrith to the family seat in Perth and Kinross.

Those 400 miles in 26 days covered a fair chunk of Stewart’s vast Penrith and the Border constituency. Among much else, he met haaf netters, camped on Blencathra, visited a Wigton council estate and crossed the Solway Firth on foot. At times that part of the walk was a wade through waist-deep water.

The book’s third element is the man who explains where much of this vigour comes from. Brian Stewart accompanied his son on part of the Hadrian’s Wall walk but proved too frail to do much of it.

The fact that this was even considered, when Stewart senior was 89 years old, says much about this remarkable man. A veteran of the D-Day landings, he became the second-most senior person in the British secret service. He also had a career as a colonial civil servant in Malaya. As a child Rory’s adventures with his father included exploring that country’s jungles and the Great Wall of China.

Throughout his eighties Brian Stewart remained impressively energetic. His son frequently rang him for advice. It appears a charmingly close relationship. They were “daddy” and “darling”.

Brian died last year, at the age of 93. He looms large throughout The Marches , whether or not he is physically present. Whenever we are hearing the book’s author, perhaps we are also hearing his father.

Stewart, 43, acknowledges the influence. “I joined the same regiment in the army, I went to the same university, I joined the Foreign Office. He’d made most of his career in Asia and learned languages. I went to Asia and learned languages.

“I realised in ways I struggled to before I wrote the book that a lot of my views on the world, which I always thought of as my own, are really his. The fact that he was a very fierce believer in the United Kingdom and a fierce opponent of Scottish independence probably made me feel like that. And if he’d felt the other way maybe I would have felt the other way.”

There were also attempts to tread his own path: literally, in the case of a 21-month walk across Asia. “Perhaps I was doing that because that’s something he hadn’t done.”

In the main, though, Stewart is proud to be his father’s son. Walking with him and writing the book threw new light on their relationship.

“I tried to make a relationship with him based on knowledge. Really it was about feeling and about doing things. He was defined by what he did.”

Was Brian Stewart an intimidating father as well as an inspiring one? “He could have been very intimidating because he’d been this amazingly successful intelligence officer and a very confident soldier. But partly maybe because he was 50 when I was born, he was very good at making me feel as though I was special.

“In many ways he was much better at things than I was but he concealed it from me. He would suggest that I could sing when I’m a really, really bad singer. He was a very serious musician but he never let me see that.”

We are made by places as well as by people. Both are explored in The Marches . One theme recurs. For all its sense of permanence, Cumbria has always changed and continues to do so.

As well as haaf netters, Stewart met people in much less traditional roles. “I got a sense of the incredible variety of people that now live in Cumbria. It’s impossible to assume anything when you knock on a door.

“One of the most successful businessmen in my constituency is a man who buys second-hand photocopiers in Britain and ships them to China. The sheep farmer who can count in Cumbrian and whose family have lived there for hundreds of years; actually what he cares about most in life is that he bought a motorcycle from some New Zealand travellers and used it to ride to Afghanistan in the 1970s.

“It’s very dangerous to think that you can generalise. I think it’s important for me as a politician to realise that. You could look at your constituency and say ‘It’s a rural place,’ or ‘It’s a place dominated by tourism.’ And then you would try to create policy on the basis of that. Yes, it is those things. But it’s 10,000 other things as well.

“Governments have to be quite humble about their understanding of the modern world. You can’t throw your weight behind one particular industry. You look for things like broadband which can be used by everybody.”

National identity is a thread running through The Marches . People who Stewart met expressed theirs in both pride and prejudice. He barely conceals his bemusement at the differences on either side of the border.

Hadrian’s Wall is a “surreal tragedy”. England and Scotland exist because of a line drawn on a map by a Roman 2,000 years ago. Communities were divided and divisions created. Today the differences have grown deep roots.

“In terms of soil, climate, history, DNA, we are the same people as the people in southern Scotland. But by putting a wall down you invent these two things called England and Scotland.

“It is very strange. I thought when I began that because nationalism is often about history or battles from the Middle Ages, that I could discuss those issues with nationalists.

“But it doesn’t help you at all. People have these very powerful beliefs and views. They’re not necessarily rooted in very detailed stories about a particular history or a particular soil. They’re maybe questions of emotion. People’s nationalism becomes stronger in the moment at which they feel they’re losing their identity.”

Stewart has long urged politicians to learn from history, in the case of Western intervention in distant lands. Researching 16th century Borders’ history revealed parallels with 21st century wars.

“One thing I learned which has been very useful to me in my work now in international development is that people blamed Cumbrians for the violence on the border.

“They thought that we were just a wild and aggressive people. It became clear to me through my research that actually that violence was caused by governments funnelling in money and exploiting the border to fight a proxy war between two capitals. There was nothing inherently violent about the population. They were victims.

“Reading documents and seeing that in 1520 some official in London is saying ‘On the twelfth of December I want the Nixons to attack Jedburgh. On the thirteenth of December I want the Routledges to attack Hawick.’ You realise that what was presented as the wild west was incredibly bureaucratised.

“And that has real implications for Syria or Afghanistan or the Balkans. Foreigners looking at these places will try and tell themselves comforting stories: ‘It’s a wild people. They’re naturally warlike.’ And fail to acknowledge the ways in which governments, politics, power, structures, are actually behind the problem.”

There are opportunities to make this argument in the international development role Stewart has held since July. His constituency is even bigger than Penrith and the Border: the Middle East and Asia.

“I love it,” he says. “I think it allows me to balance what I like to do to serve Cumbria and to make use of my previous experience in other countries. The biggest issues on my watch are Syria, Iraq, and particularly the refugee crisis.”

Stewart has, of course, enjoyed a luckier life than refugees. But he still knows the pain of being separated from a loved one, if only by a long life reaching its end.

“I still wake up in the morning thinking about him. As a young person growing up, he was the person I was most interested in in the world. He would get out of bed at six o’clock in the morning and spend the first three hours of every day playing with me. That’s almost the most intimidating thing that he did. Because I don’t feel I’m able to spend as much time with my son [two-year-old Alexander] as my father spent with me. And I feel guilty about that.”

What comes to mind when Rory Stewart thinks about his father? For half a minute he stares into space, flicking back and forward through the years. Finally he settles on a memory from a time when life was simpler and more secure.

“What I remember most strongly of all is as a younger person being held against his chest as he sang. He had a beautiful voice and his whole ribcage would echo. And I could then hear this incredibly powerful voice with these rolled Scottish ‘Rs’, because he kept his Scottish accent in his singing.”

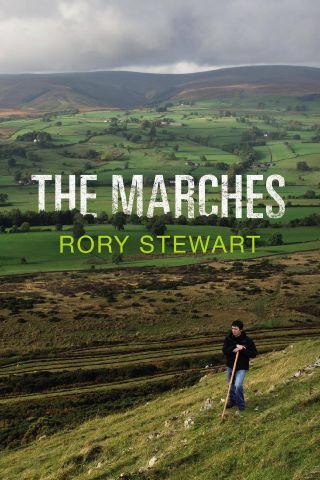

The Marches by Rory Stewart is published by Jonathan Cape.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here