Jeremy Suter was rather sleepy when he arrived for his job interview at Carlisle Cathedral. He’d been driving all night, up from Sussex.

The first task asked of him was to play the cathedral organ. “I got on the organ bench and I immediately felt at home,” he recalls. “The organ was doing everything I wanted it to do.”

So he got the job. That was exactly 25 years ago. And, on Tuesday, Jeremy will be back on that organ bench, for a recital commemorating his quarter of a century as the cathedral’s Master of Music.

He has been involved in music for much longer than 25 years though. In fact, for most of his 65 years. And rather than singing, composing or mastering any other instrument, he has always felt drawn to the organ.

His love of it has taken him around the south of England and to America, before leading him to the organ bench at Carlisle Cathedral.

Jeremy first heard the instrument at the church in London where his father was vicar. Later he heard it every day at Westminster Abbey, when, aged nine, he became a chorister.

“The music training we got was quite intense. The choir sang at two services a day, and sometimes three on Sundays – with rehearsals in between. I probably spent something like four hours a day with music in one way or another.”

When a sore throat stopped him singing he would still be there, turning the pages of the music for the organist. That was when the bug bit.

“I was just mesmerised, watching the organ being played to a high standard.”

So during the holidays he began organ lessons. But a proficient pianist won’t necessarily be a proficient organist.

While playing the piano requires nimble fingers, the organ requires nimble feet as well.

A set of pedals play the bass notes and he says: “You play the sharps and flats with your toes and the naturals with your heels. The hardest thing is that your left hand is no longer playing the bass line.

“Most organ teachers want you to have at least Grade Five in piano before you start.”

Jeremy won a music scholarship to Harrow School but left a year early to go to the Royal College of Music. For a time he leaned slightly more towards the piano – but a comment from his teacher pushed him back towards the organ.

“He said: ‘Look, Jeremy, you’re never going to be a concert pianist.’ My ambition was always to be a cathedral organist.”

The Royal College taught the technical, practical skills but for more academic training he studied music at Oxford University.

It was much more about the theory. “It used to be said that you could get a degree in music without being able to play anything.”

But it was an extremely valuable experience for him. All Oxford colleges have an organ scholar, whose job is to assist the organist and accompany the college choir. And as Magdalen College’s organ scholar it meant working with director of music Bernard Rose.

“He was an inspirational musician. I learnt an awful lot from him. They were three very significant years.”

More study followed, in the USA. The University of Pennsylvania was offering a scholarship to an Oxford graduate. Jeremy was awarded it, though admits he didn’t face fierce competition. “I was the only person who applied.”

As well as further study, he played the organ at a church in Philadelphia and took the opportunity to travel around the USA and into Canada. And when he returned to Britain he got a job back at his old college.

Jeremy Suter Bernard Rose was taking a sabbatical and Jeremy filled his shoes.

“I was a junior lecturer, so I got the chance to give tutorials – and I also got to dine at high table. I acquired a taste for high living!”

But an academic job didn’t appeal long-term. All Saints’ church in Northampton was looking for an organist and its new vicar was seeking to revive its boys’ choir.

Jeremy sought recruits from the church middle school, also did some teaching there, and got to know the deputy head, Sue – who later became his wife.

“I was there for six years, but I was hankering for a cathedral job.”

That came up at Chichester Cathedral in Sussex. He went there as assistant organist, Sue continued her teaching career and the couple had their two daughters there – both now in their 30s. “We had 10 happy years,” says Jeremy.

When the Carlisle job emerged it was a promotion. But the interview was the day after a major school concert in Chichester which he didn’t want to miss.

“The only way to get here in time was to finish the concert and drive up through the night. So I arrived not having had much sleep, not sure what would happen.”

Like many of those who come to Carlisle for work he had visited the Lake District but wasn’t familiar with the city. “I suppose I expected it to be a bit like Keswick,” he admits. “But we were pleasantly surprised by Carlisle.”

Their daughters, then seven and nine, settled in quickly at St Michael’s School in Dalston and then moved on to Caldew School. And the new job came with a house – 20 seconds’ walk from his place of work in the cathedral.

As a lover of the organ, Jeremy’s favourite composer is probably the greatest organ composer, JS Bach. “When it’s right, everything fits together beautifully.”

He is also a fan of the early choral music of Tallis, Byrd, Palestrina and de Victoria. And he admits to a liking for jazz and The Beatles.

However the job wasn’t all playing the organ and conducting the choir. There was more admin involved.

“I was given this old Amstrad computer I had to learn to use. I found I was spending more time at the computer keyboard than the organ keyboard.”

Now there’s a part-time administrator to help. Because music at the cathedral has expanded hugely during Jeremy’s 25 years.

For a start there are four more choirs. There’s the Carlisle Youth Choir for boys and girls aged from 13 to 21, which sings at evensong once a week. There’s also a choir for girls under 13 to mirror that of the boy choristers. Combining them with the boy choristers for certain services and concerts also works well.

“There’s a school of thought that says if you mix them, the boys will tend to drift away because it’s seen as a rather ‘cissy’ thing to do, but that’s not been the case here.”

When an outreach programme was set up, where cathedral musicians visited primary schools to introduce them to singing, it gave rise to yet another youth choir, Cantate.

It is led by assistant organist Ed Taylor, one of those leading the outreach programme, who found that some of the youngsters he introduced to singing wanted to go on doing it.

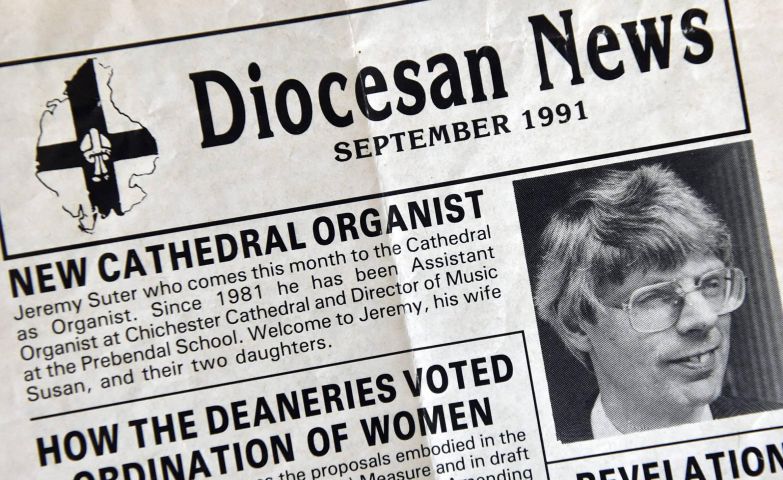

The Diocesan News featured Mr Suter's arrival They meet once a week in the Fratry and sing classical music, jazz, pop and songs from musicals.

Jeremy adds: “We also have an adult voluntary choir called Carliol Choir. It had existed but folded, so we got it going again.”

Carlisle Music Festival started in 2000, but shortage of money and disappointing audiences prevented it from happening this year. There are hopes to revive it next year, though not as an annual event.

Yet Live at Lunchtime is doing well – and about to resume. From April to June and September to November, live music of all varieties takes place in the cathedral on the second Tuesday of each month, between 12.45pm and 1.30pm. The autumn season begins on September 13 with a performance by saxophonist Roz Sluman.

But the next live performance there will be Jeremy’s recital, at 12.45pm on Tuesday. It will feature organ music by Bach, Mendelssohn, Howells and Robert Prizeman and one work almost everyone will recognise, the theme to the BBC’s Songs Of Praise (Stephen Cleobury’s Toccata ). Admission is free but there will be a collection for the Carlisle Cathedral Choir Association.

Though 25 years might seem like quite a milestone, Jeremy points out that it doesn’t match his immediate predecessors. Andrew Seivewright served 31 years, Dr FW Wadely did 50 and Dr Henry Edmund Ford clocked up no fewer than 68.

But Jeremy has no plans to retire yet, so couldn’t he reach their long service levels? “Medical science would have to advance quite significantly.There must be something in the water or the air that encourages people to stay.”

And whatever happens he’ll remain in Carlisle. “It’s a great place,” he says. “A concert hall would be good – The Sands Centre’s not purpose-built for music.

“As an area to bring up children it ticks all the boxes, it’s got a good train service and it’s got good curry houses. That’s another of my passions – a good curry.”

He admits to another. “Most Sunday afternoons if I’m free you’ll find me at the station, watching the Flying Scotsman come in.”

So he’s trainspotter as well as a musician? “I’m not fully qualified,” he counters. “I haven’t got an anorak!”

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here