Take a trip out to Solway Aviation Museum when it re-opens on Good Friday. Among the vintage planes, photos, books, explanatory boards and souvenirs you’ll see two rockets, each nine and a half feet tall.

They were built for carrying nuclear warheads, to be launched against the Soviets in the event of World War Three.

Thankfully that war never happened And the rockets were soon overtaken by newer technology, and by their cost.

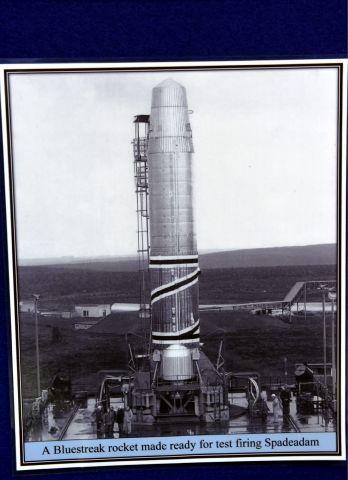

But the Blue Streak rockets and their engines, which were built and tested in Cumbria, are one of the battle scenes of the Cold War that people aren’t always aware of.

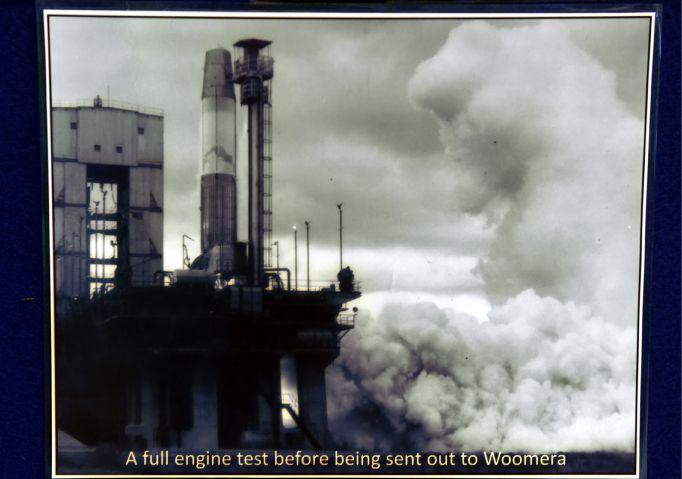

Everyone knew the rocket engines were being tested at Spadeadam, as Duncan Turner, secretary of Solway Aviation Society, explains. The noise and impact made that obvious.

“They produced 150,000 lb of thrust,” he says. “When they fired, Carlisle shook.

“People knew they were testing rockets but they didn’t know what it was about. Spadeadam didn’t say: ‘We are building a nuclear deterrent here.’

“You had to let people know because of the noise, but there was very little information going out.”

Even today it isn’t often mentioned. “Spadeadam doesn’t flag it up for everybody to know about.”

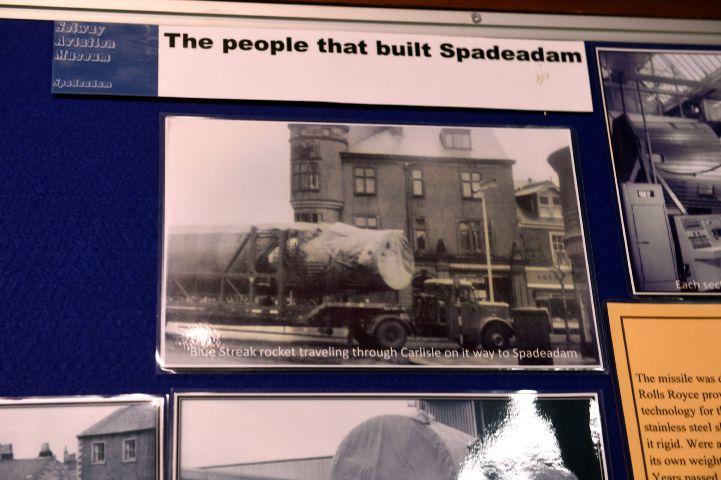

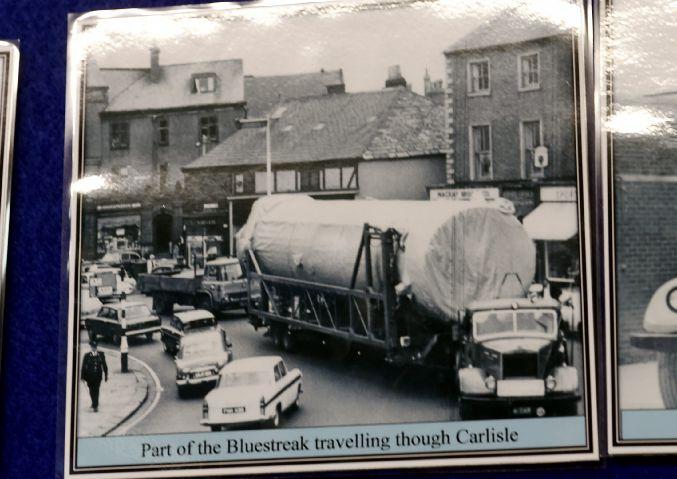

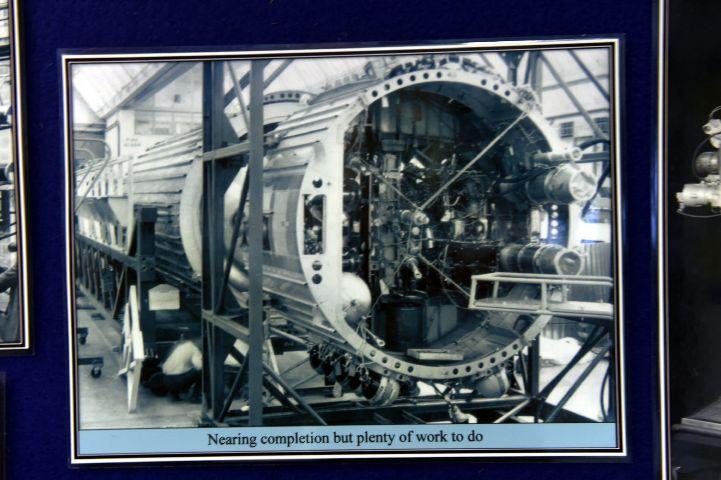

But the aviation museum does. Solway Aviation Society runs the museum at Carlisle Airport, and Duncan says: “It’s a chunk of the museum. We have two rockets and an engine bay about 12 feet in diameter, where the engines were fitted, and photos of them being through the centre of Carlisle along Warwick Road, before the motorway was built.

“We tell the story of how it started out.”

After World War Two, Britain’s nuclear weapons were free-fall bombs delivered from bomber aircraft. But it soon became clear that if the country wanted to have a credible nuclear deterrent, it would need ballistic missiles, those that could be launched from here and shoot across the continent to the Soviet bloc.

It was also bound up with politics – the feeling that if Britain was to look like a major world power it ought to have the latest weapons of mass destruction.

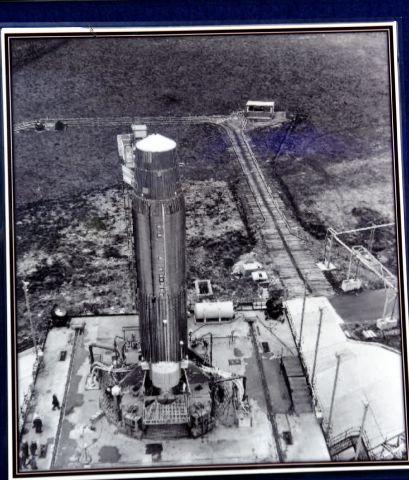

So Blue Streak was chosen for it, and Spadeadam was chosen as the place for its rocket engines. It was remote and largely uninhabited in 1957, when the Blue Streak test centre was built.

“The warheads were never here,” Duncan stresses. “Spadeadam was for testing the rocket engines. And it employed quite a few people.

“There were people around Carlisle at the time who worked at Spadeadam, and they built houses in Brampton for some of the others who worked there.”

Today many question whether renewing Trident is the best way to spend scarce money, and if it will really help defend us against present-day threats such as terrorism. But in the sabre-rattling days of the Cold War, the idea of a nuclear deterrent was widely supported. Duncan recalls the thinking of the era.

“If your enemy is bigger than you then he’s going to pick on you. That’s why you need a weapon. If you’ve got something to hit him with, he’ll think twice.”

However it soon became clear that Blue Streak was’t ideal. It was too expensive and too vulnerable to a pre-emptive strike. We were told we would receive a “four-minute warning” if the Soviets launched an attack against us but Duncan points out: “It wasn’t kept fuelled. Refuelling it before firing would take half an hour to an hour.

“There were also plans to put them in underground silos, but because of the expense that was dropped. We were a pretty poor country, trying to do it all.”

And the price was going up and up. In early 1955 it was expected to cost £50 million but by late 1959 that had reached £300 million – and it was only going to get higher as it neared completion.

So in 1960 it was cancelled. And – partly to avoid political embarrassment from the cancellation – another purpose was found for the rockets.

Britain joined with France and West Germany to launch another project, the European Launcher Development Organisation, (ELDO). “We got together to make launching vehicles for satellites. The would have been communications satellites, not necessarily for military use.”

It was supposed to represent a European alternative to the American and Russian dominance in satellite launchers, with Britain, France and West Germany each contributing components. But Duncan explains: “When they were launched, either the French bit went wrong or the German bit went wrong. So Britain eventually pulled out.”

That was in 1972. Four year later, in 1976, Spadeadam became an RAF base.

And its role in the Cold War was never really made public.Then in 2004 tree-felling there uncovered the remains of an abandoned site for a missile silo. English Heritage and the RAF investigated – but it had apparently been kept so secret that no plans from the period exist.

It can come as a surprise to local visitors to the aviation museum.

“Young people don’t know about it,” Duncan finds. “Older people will have known about the rockets but may not have known what they were for, and when they find this was on their doorstep they are a bit surprised.”

It can also come as a bit of a shock to its many overseas visitors. “We get people from China, Australia, New Zealand, Canada and America. They don’t know we were involved in nuclear weapons.”

The museum re-opens on Good Friday and will be open on Fridays, Saturdays, Sundays and bank holidays until Sunday, October 30. It is open from 10.30am until 5pm, with the last visitors admitted at 4.15pm.

Admission costs £6 for adults and £4 for pensioners and children aged from six to 16. A family ticket for two adults and up to two children costs £15.

For more information go to www.solway-aviation-museum.co.uk

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here