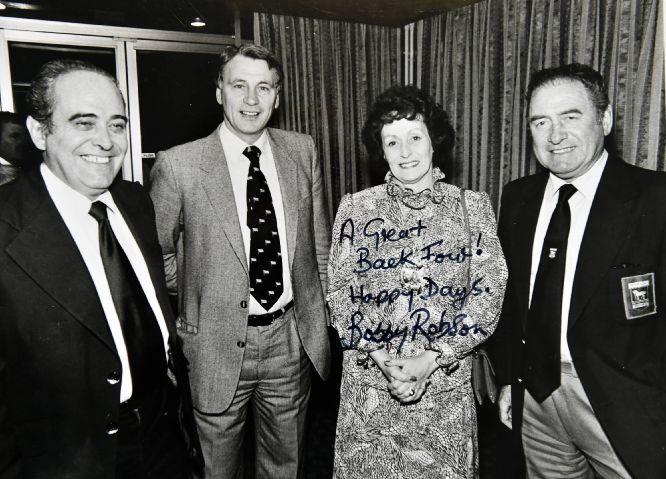

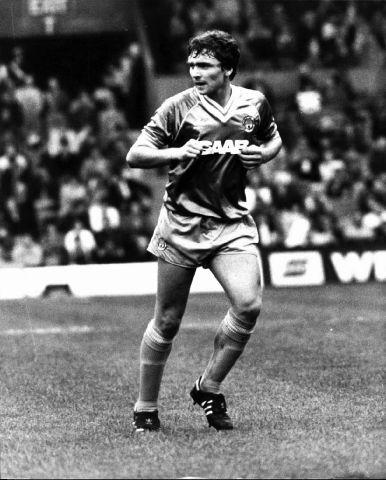

The typewritten lists are long and formidable. Other names glow from carefully clipped newspaper cuttings. The copy of a faxed message indicates a further small triumph, while a photograph displays our modest hero next to Sir Bobby Robson.

John Carruthers, talent spotter extraordinaire, died 20 years ago but his work is preserved by the game's history. It is also contained in a small maroon file, which recently came into the proud possession of his son, also John.

John junior opens it carefully, mindful of the treasures within. His father's background as a scout was a story of many years but this new find captures its many highlights.

The names are significant, Kevin Beattie and Paul Gascoigne the greatest. Carlisle interest is further served by the appearance of David Geddis, Robin Turner, Steve McCall and Paul Simpson.

A later fax, issued to Sunderland AFC, features Carruthers' handwriting, and the recommendation that an outstanding boy called Chris Lumsdon - "the best schoolboy midfield player in the North East" - be signed on YTS forms.

They are the small but significant records of an unassuming man. "He wasn't someone who would stand on a podium and talk about what he had done, but there would be cuttings he would clip out and stick away in a cupboard somewhere, so he could look back," John says.

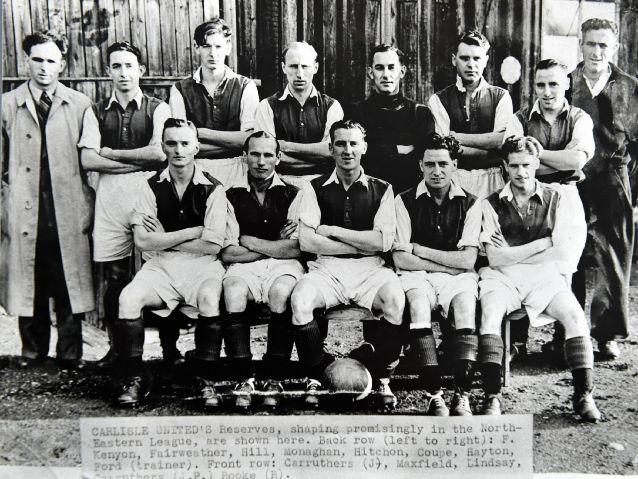

There was much on which Carruthers, whose family are from Morton in Carlisle, could reflect. A footballing life that began with Carlisle United's reserves and a professional offer from Portsmouth - rejected on grounds of homesickness - assumed much greater renown when Carruthers began scouting, initially for Queen of the South and later for Ipswich Town.

"The trigger," John says, "was that he had a close friend, Geoff Twentyman, who was by then the chief scout for Liverpool. Dad had recommended Kevin Beattie to him and the famous story goes that Kevin caught the train to Liverpool, wasn't met by any officials, and instead of finding out where he was supposed to go, ended up on the train back home again.

"My father knew another guy locally, Donald Lightfoot, who knew Bobby Robson. He bumped into him and mentioned that Kevin had come back up to Carlisle. Word was sent to Bobby, and Kevin went down to Ipswich. He was signed after one game."

This was the nod that earned Carruthers the great Robson's trust. He joined the Suffolk club initially as a part-time scout, juggling it with his sales job for food firm Costa & Company, and later went full-time, scouring Cumbria, the north-east and southern Scotland on behalf of a great, intuitive manager whose policy, in the absence of big-club wealth, was the sourcing and promotion of youth.

Beattie was some find; later described by Robson as the best English talent he had seen. "Dad had watched Kevin when he was 13 or 14 years old, and wondered why Carlisle United had never had a look," John says. "The lad clearly had potential. He was streets ahead of anybody else at that age at the time. And a few years later he was playing for England."

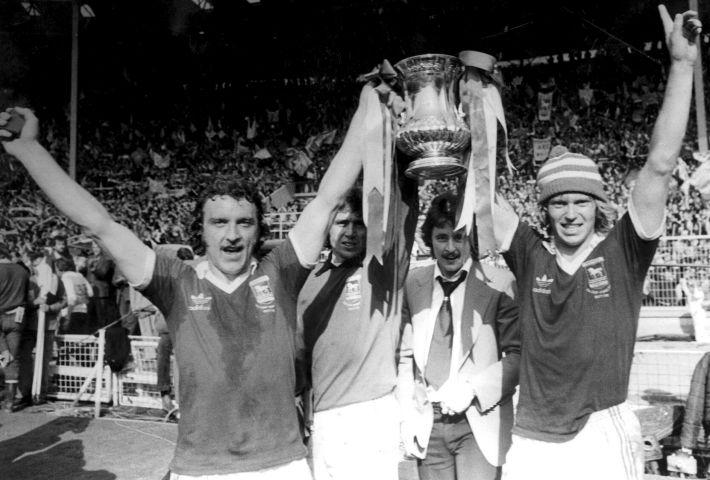

There became a regular stream of talent from this area to East Anglia. The 1978 FA Cup final, won by Ipswich against Arsenal, memorably featured two Carlislians, Botcherby's Beattie and Geddis. Another, Harraby's Turner, only missed out because Robson had opted for Micky Lambert as a substitute, in his testimonial year. When the UEFA Cup was also won, in 1981, Carlisle's Steve McCall - a Morton lad - was among the medal-winners.

This was a further tribute to Carruthers' eye - but it did not find universal favour in his home city. "For a time there was a bit of stick thrown at him because of the local talent he was sending out of Carlisle," John says.

"His answer always was, 'I sent Kevin Beattie down to Ipswich when he was 16. At that time, in the early 1970s, professional football clubs would sign players on at 14 years old. Basically, Carlisle United had two years to look at him, and sign him, but they never did. Why, I don't know'."

Did the barbs hurt Carruthers? "I think, without him saying, it did a little bit," John says. "I remember one article in the paper many years ago when he was asked about this. One thing he said was that he'd have loved, at one time in his life, to have scouted for his home-town club. But he was never asked."

While the Blues of the 1970s did not benefit from Carruthers, his own club certainly did - even if there were a few near misses. He recommended a Morton School boy with a smart left foot, Simpson, but he opted instead for Manchester City.

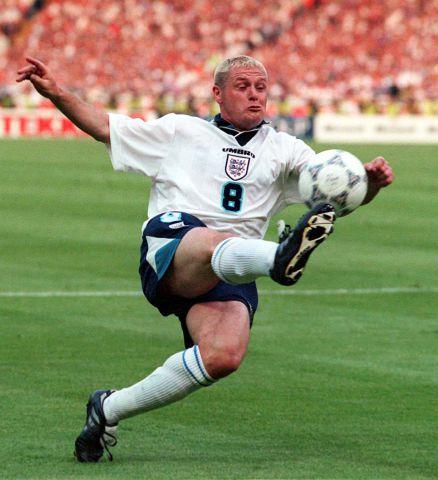

The podgy lad playing for Dunston Working Men's Club in Gateshead is another tremendous tale. "Dad sent him down to Ipswich for a trial when he was 13 or 14," John says. But he was small, a bit fat, a bit slow, and had a stinker. On that basis he didn't get signed.

"A couple of years later he had grown a bit, slimmed, got a bit quicker...and that was Paul Gascoigne. My Dad had obviously seen something in this little, fat, slow boy. He could probably pass a ball 30-40 yards onto somebody's toe."

The eventual flourishing of Gazza is an example of the scout's precarious lot. "I remember Dad saying it's not an exact science, watching young boys. You've got to watch them four or five times, sometimes more. It's not just about ability. Has the lad got the desire, the will, the right mental attitude? Does he want to succeed? There are late developers, boys who want it more, boys who go in the opposite direction, boys who find other things in life."

Analysts and technology have widened scouting's modern scope, but Carruthers was from a more traditional time. "Sometimes a scout would be standing on a non-league ground in the middle of winter, absolutely chucking it down, and probably thinking, 'what am I doing here?' But it didn't seem to faze my Dad," John says. "He just had that desire to do the job.

"He would sometimes watch two or three games a day, often in Carlisle at the Sheepmount at 10am, then maybe one over in South Shields at 1pm and another later. It was very time-consuming, a lot of miles, and he'd think nothing of answering the phone very late at night, when one of his contacts called. My Mam, Jean, and sister Alison were always there too, supporting in their own way, taking calls and messages.

"It was hard work, and a lot of scouts weren't really well looked after at the time. Fortunately my Dad had the right man and club backing him. He would often say that he didn't work for the biggest club in England, but he did work for the best manager, chairman and board of directors. And Ipswich Town benefited from the players he brought, for next to nothing."

Robson was indeed appreciative, and it was because of Carruthers that the great man came to Carlisle in 1983. The new England manager held court in the Shepherd's Inn, in a panel discussion hosted by the late broadcaster Eric Wallace.

"I think it was a thank-you to my dad," John says. "Bobby was a total gentleman. He had presence about him. He could talk to anybody, whether the cleaner in the changing rooms, or the chairman."

Carruthers continued working under Robson's Ipswich successors, Bobby Ferguson and John Duncan, before leaving to scout for Sunderland from 1990-95. His recommendations included Lumsdon, Paul Thirlwell and Lee Howey, while an earlier name on his list connects the three clubs of Carruthers' life: Eric Gates.

Carruthers also cared about his trade. He attempted, in the nineties, to form a scouts' union that would have protected the talent-spotters and funneled more of the game's extraordinary new wealth back to local clubs where Beatties and Gascoignes would emerge.

This fellowship was felt deeply. "He'd be scouting at somewhere like North Shields, and he knew there'd be half a dozen other football scouts there watching the same game," John says. "The common denominator was, they all got on well.

"There was the odd bad apple, but the majority had mutual respect. If one of them won a player, they would shake hands and no hard feelings."

Two years after ill health led him to step away from scouting, Carruthers died in 1997, aged 70. As a result he missed the game's lurid explosion, at Premier League level at least. John is not sure his father would have enjoyed the indulgences of the modern player, the faster, more fragile game, or the way money now conquers all.

These days, too, an illustrious player is more likely to thank a Wyscout programmer for his fate than an anonymous figure on a touchline.

"I think," John says, closing the treasure trove, "my Dad was probably involved in the game at the right time. A simpler time, where, if you worked hard, did your job, got on with it, made your contacts, if you liked people and people liked you...that seemed to be enough."

Lasting appreciation had, it should be stressed, come to Carruthers before he passed. It arrived in the phonecalls, letters and Christmas cards from those Carlisle boys he had sent towards stardom.

It also came, backhandedly, from the very greatest. The story goes that, after a game at Anfield in the late 1970s, Bill Shankly cornered Beattie in the players' lounge. "As a manager I haven't made too many mistakes," he confided. "But missing you was one of them."

It was a private moment, packed with meaning. The boy from Botcherby, John Carruthers' greatest find, kept the secret until after Shankly's death.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here