For all the research, all the interviews and all the archive trawlings, the exact nature of the incident that would cost Adrian Doherty his career has proved almost impossible to pinpoint.

Yet this in itself tells a tale. The moment the richly talented Manchester United player suffered a knee injury in a reserve game in 1991, setting in train events that would deprive football of a potential superstar and later end in tragedy, is recalled hazily at best.

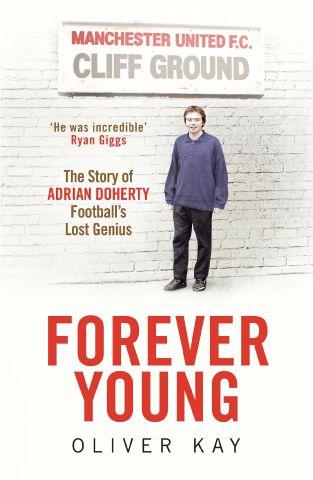

Oliver Kay, author of a book about the young Irish wizard who was rated as highly as his Old Trafford contemporary, Ryan Giggs, says he has tried not to "draw any morals" from his story. If there is one at all, it is about the precariousness of a sporting life - how all careers exist, in some barely visible way, on a knife-edge.

Certainly, there was no way that the 17-year-old Doherty could have expected the morning of February 23, 1991 to have such a profound effect on his life - nor could Carlisle United have anticipated their own unwitting part.

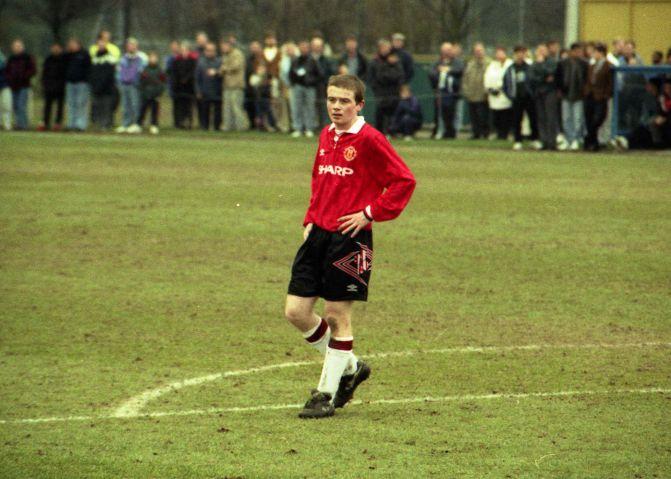

The fateful second-string encounter with Carlisle's reserves took place at the other United's training ground, The Cliff, at a time when the prodigous Doherty was on the very brink of first-team involvement under Alex Ferguson, the illustrious 'Class of 92' yet to emerge.

Doherty on the right and Giggs on the left was how many sages predicted Man Utd's future would be brilliantly shaped. Yet at some stage in that reserve game, a 50-50 challenge left Doherty "down in a heap" and unable to continue.

A ligament sprain was diagnosed, yet attempted comebacks faltered, and in the summer a cruciate tear was established. After a period of rehab, Doherty again tried a comeback in a B team game against Marine, but this time his cruciate went completely.

His career was never the same, and in a few short years Doherty drifted out of the game. "The view from everybody," Kay says, "is that the damage was done in that game against Carlisle."

This is supported by interviews Doherty did around the time - yet not the slightest blame is aimed at Carlisle. There is no record of a dangerous or dirty tackle that floored the young Northern Irishman. The fact nobody can remember exactly how it happened suggests how innocuous it was felt to be at the time.

The only context is provided when Doherty's contemporaries recall the general nature of reserve games with the Blues in the Lancashire League in those early-1990s days. One, Peter Smyth, is quoted in the book, Forever Young , as saying such encounters would typically leave Man Utd's young prospects "black and blue". "You would just get walloped," Smyth says.

This was Carlisle in their poor, pre-Michael Knighton days, where fans of the first team were being underwhelmed by the displays of big summer signing Eric Gates, as the club slipped further into a financial hole. Their reserves were a mixture of local lads, apprentices and wannabe pros, coached by men like Aidan McCaffery, Mally Burgess and Dave Heslop - yet one of their players, Jeff Thorpe, says he cannot recall any intention to subject Man Utd and Adrian Doherty to a bruising.

"No more so than normal," says Thorpe, whose professional career with the Blues flourished in the mid-90s before he also suffered injuries. "It would only be in terms of setting your stall out, looking after yourself. I can certainly never remember anyone saying specifically, 'let's get walloped into them'.

"Maybe that's a perception top teams had when lower-league teams came to them. But we still wanted to play football and do the right things. And you have to remember, most of the time you couldn't get near their top players."

Thorpe, who at 17 had made his first-team debut for Clive Middlemass' Carlisle team in 1990/91, struggles to recall the game when Doherty went down, but does appear to have been involved. Carlisle's reserve line-up, taken from a Blues' match programme, is listed as: Ian Taylor, Lee Armstrong, Mike Bennett, Geoff Bell, Derek Townsley, Piero Baldotto, Eamonn Elliott, Calum Graham, Marcus Thompson, Craig Goldsmith, and Thorpe, from Cockermouth.

"I don't think there's any kickers in that team," says Thorpe, now a senior lecturer in medical and sports sciences at the University of Cumbria. "Peds [Baldotto] will have got stuck in, and Eamonn was a little Jack Russell in midfield, but nobody in that side were dirty players."

Doherty's nickname, 'the Doc', sparks a faint memory. "I'd be left-midfield or left-back. I might even have tackled the bugger," Thorpe says. "I'd certainly be up against him - probably me tracking back rather than him tracking back to get me!

"The truth is that, because of the ages of the players in those games, nobody had really made it, so only the extra-special memories stand out. I remember once playing against Giggs, when we had a free-kick on the edge of the box. It was hit at him, he chested it down, and ran up the other end and scored, beating three or four of us in the process."

Doherty would also do similar things and, it can be assumed, was one of Man Utd's most able players when Carlisle's fringe players climbed into their "little mini-bus, not always with enough kit," and made their way to The Cliff, a place Thorpe recalls as "nothing special" in itself, but with a certain aura, as the great Ferguson often watched on from his office or pitchside - and where the visiting Carlisle players would marvel at the Red Devils first-team players' cars.

As Carlisle's players made their way back up the M6 later that afternoon, "with two quid to spend in the services", Doherty's chances of playing in Ferguson's team were receding. The boy from Strabane had been pencilled in for his first-team debut at a time when Man Utd were competing in League, Rumbelows Cup and European Cup Winners' Cup, with a squad where certain big names - Danny Wallace, Neil Webb, Bryan Robson - were susceptible to injury.

A game against Everton on March 2 may well have seen his bow, but instead, with Doherty sidelined, a skinny Giggs came off the bench for his own, historic debut, as Ferguson junior, Darren, started in midfield.

Giggs embarked on one of the great careers, yet Doherty was facing something which, at the time, was often fateful. "By the mid-90s recovery rates from cruciate injuries had improved considerably," Kay says. "But at that stage it was seen as a bit of a career killer."

Doherty, it is reported, found the long, futile days of rehab a torment. "By the stage of the Marine game it was hopeless, really," Kay says. "Adrian's other big interests were music, writing poetry, reading about religions and philosophy, things like that. He'd immerse himself in those to the point where they kind of took over. It got to the stage where he recognised that football was making him miserable, and other things weren't."

A vivid picture in the book is painted of a young footballer apart. Doherty is described as a Bob Dylan obsessive who was at odds with the traditional "banter" of the dressing-room; a teenager who was almost "anti-materialistic" in how he dressed, an apprentice who would ride to training on a rusty old bike, a boy who would give his last £5 note to a homeless person, a player at one of the greatest clubs who would often give away his complimentary Old Trafford tickets in favour of busking in Manchester city centre.

"Mostly after that Carlisle game it was misery, in football terms," Kay adds. "He barely played after that. So when he left the game it was a relief in some ways. He would play his guitar in bars, at open-mic nights. You'd find him in dingy, smoke-filled pubs."

It is stressed that Doherty's years after football were far from unhappy. "He just moved on," Kay says. "There are some young players whose lives would have been empty without football. Adrian didn't obsess about the game. When he lived in Galway for four years, a lot of people didn't know he'd been a footballer.

"Maybe that meant shutting it out in his mind. But everybody I spoke to described him as a happy-go-lucky, lovely guy, with no trace of bitterness."

The tragic phase of the story came when, aged 26 in May 2000, Doherty had gone to the Netherlands to work for a furniture company. The intention was to make enough money to travel further through Europe, attend music festivals and further broaden an open mind.

Yet one morning in The Hague - in circumstances which are again impossible to nail down - he slipped and fell into a canal. He was unable to swim because of a water phobia and, after a month in a coma, he died.

Kay says Doherty's family have since had to endure hurtful speculation about how this happened, yet there is little to support suspicious theories. There was alcohol in Doherty's system, from a night out the previous day, but nowhere near enough to suggest a drink-related misadventure. No drugs were involved, while there is no evidence towards suicide. "He was enjoying his life and looking forward to doing new things," Kay says.

The tragedy, then, is of a life cut short, rather than a career that never happened. Yet there is good reason why the cover of Forever Young describes Doherty as 'football's lost genius'. Had the young man lived today there would still have been poignancy in the loss of what many people felt was a quite stunning ability with a ball.

Carlisle's own part in his sad downfall could easily have been played by someone else, too. "Everyone says you make your own luck in football," Jeff Thorpe says. "But not everyone gets that chance."

Forever Young: The Story of Adrian Doherty, Football's Lost Genius , published by Quercus, is out now.

* With thanks to David Steele for his help with research

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here